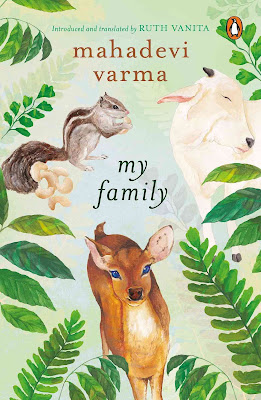

(It's been a while since I did a longish review-essay for Scroll, but I was very taken by this translation of Mahadevi Varma’s 1972 book Mera Parivar – a collection of pieces which suggest that her growing attentiveness to the world of animals and birds was central to her development as a writer. Here’s the piece) Reading the lovely new book My Family – a collection of short pieces by the celebrated Hindi poet Mahadevi Varma about the animals and birds in her life, originally published as Mera Parivar in 1972 – two early passages leapt out at me. Taken together, they are indictments of how often and how easily the bond between humans and non-humans is underestimated or glossed over.

Reading the lovely new book My Family – a collection of short pieces by the celebrated Hindi poet Mahadevi Varma about the animals and birds in her life, originally published as Mera Parivar in 1972 – two early passages leapt out at me. Taken together, they are indictments of how often and how easily the bond between humans and non-humans is underestimated or glossed over.

The first is from the introductory note by the translator, writer-academic Ruth Vanita. Some of Mahadevi’s biographers and critics, Vanita tells us, barely acknowledged Mera Parivar in their studies of her life and work. Even as they tried to understand Mahadevi through her other writings, or offered psychological profiles of her as a repressed or unfulfilled woman “longing for companionship” (presumably because she remained unmarried and lived in a hermitage-like environment for most of her life), they didn’t attach much importance to her relationships with non-human creatures.

And yet here is Mahadevi Varma herself, in her “Atmika” (preface), describing – with intensity and precision – a life-changing moment she had as a child, when she rescued a little chick that was destined to be cooked for dinner. She writes of her initial inability to understand why the chick had been taken away, the anguished helplessness she felt when she realised its intended fate and thought it was too late to save it. (I was reminded of Patricia Highsmith’s “The Terrapin” – one of many great stories about the innate concern that many children feel for other life forms – about an animal that couldn’t be saved from a cooking pot, and how a little boy is scarred as a result.) Most tellingly, Mahadevi explains how this incident led her to note down identifying marks for the animals and birds she knew and cared about. It’s as if she felt a moral duty to imprint their distinct features and personalities on her mind’s eye. “I had no other way to prove that I was their protector.”

Here, then, are the building blocks of a writing life: learning to observe, record and articulate. As Vanita puts it in her Introduction, “Mahadevi’s acclaimed portraits of humans, whether villagers, vendors, domestic workers or fellow writers, develop from her first recording of a non-human fellow being’s individuality.”

Despite Mahadevi’s immense stature in twentieth-century Hindi literature, and despite the importance that she herself attached to her inter-species relationships, this translation marks the first time that Mera Parivar is available in English – another reminder of its neglect. And a travesty, because every page of My Family is evidence of the centrality of the animal world not just to her daily life but to her artistic development.

*****

A cliché goes that art expresses the human condition, that the best of it is rooted in humanism, broadly defined as the transcending of the many divides, the many forms of “othering”, that cause conflict in the human world – class, gender, religion, race, caste. What doesn’t get acknowledged enough in these conversations is that such prejudice and discrimination can be extended to our collective treatment of other species; empathy for “others” can equally apply – both in the interests of our humanity and in the broader interests of the ecology and environment – to the non-human world. Creative people have addressed this in many ways – such as through the anthropomorphising of animals in literature, painting and other arts. One can understand and respect this approach while also recognising its limitations. When done well, in children’s literature for instance, it can help in the early sensitising of children to the possible inner lives of other species; but there are pitfalls attached, such as a child’s disappointment when a real-world animal turns out not to be “smart” or “entertaining” in the way that we humans define those concepts.

Creative people have addressed this in many ways – such as through the anthropomorphising of animals in literature, painting and other arts. One can understand and respect this approach while also recognising its limitations. When done well, in children’s literature for instance, it can help in the early sensitising of children to the possible inner lives of other species; but there are pitfalls attached, such as a child’s disappointment when a real-world animal turns out not to be “smart” or “entertaining” in the way that we humans define those concepts.

Either way, one can keep looking closely at animals, noting the markers of sentience and personality (things that usually leap out at you once you make an honest and concentrated effort), recognising the ways in which their behaviours can be similar to ours in some ways and very different in others. Forming relationships with them. This is something Mahadevi began doing early in her childhood, but it also became a lifelong endeavour, each new experience embellishing and adding new meaning to the ones that had come before it.

There are only seven chapters in the main body of My Family, each a pen-portrait of a specific animal or bird (except for the last chapter, which is about three creatures who played an important role in the author’s formative years). Once you have finished reading the book, you might well feel that Mahadevi could have easily written another dozen such pieces about her non-human companions. And yet, what is contained in these page is a universe of detail and observation, in fluid prose that is full of humour and warmth.

Here is a peacock named Neelkanth picking up baby rabbits by one ear with his beak (“He would often sit down in the dust with his wings spread out, and they all would play catch-as-catch-can in his long tail and thick wings”) while also being hassled by the competing affections of the peahens Radha and Kubja. And here is the baby mongoose Nikki of Mahadevi’s childhood, described as “an anarchist like us” – much like little Mahadevi and her siblings, Nikki had sneaked away from his parents in the afternoon to seek new adventures. (When Mahadevi’s mother orders her to return him to his parents’ burrow, she feels deep sympathy for the little creature. “If our father were to make us sit in front of him in a small room night and day and keep teaching us, while our mother sat nearby stitching and knitting, how would we feel?”)

There are clear-eyed, unsentimental views of the random violence inherent in the natural world: a cat finding its way into a burrow and tearing to pieces a family of rabbits; a much-loved Himalayan dog being killed by a hyena while out running errands for villagers; the cruelty of a cow being fed a needle by an envious milkman; a bad-tempered rabbit named Durmukh showing a version of toxic masculinity by attacking his own wife and children. And there are poignant descriptions of more natural deaths, such as that of the squirrel Gillu who holds on to Mahadevi’s hands on the last night of his life.  Amidst the conflict, there is beauty and tenderness. A dog named Neelu gently holds fledglings in his mouth until they are brought to safety. The peacock may be a “martial vehicle” – the steed of the war-loving god Karthikeya – but he is also, through his dancing, a practitioner of art and grace. In one of the philosophical asides scattered through the book, Mahadevi contemplates that if humans communicated only with their eyes, many arguments would come to a quick end. “Perhaps it is because of this that one’s spirit, wounded by human voices attacking one another and by the burden of meaningful words, longs to be healed and consoled by the sandal paste of these wordless beings’ fluid, affectionate gaze.” Of the languorous movements of a cow named Gaura, she writes, “There is beauty in speed, but not as much beauty as in a slow pace. The speed of an arrow can dazzle the eyes for a moment, but a flower’s slow, circular movement in a gentle breeze is a feast for the eyes.”

Amidst the conflict, there is beauty and tenderness. A dog named Neelu gently holds fledglings in his mouth until they are brought to safety. The peacock may be a “martial vehicle” – the steed of the war-loving god Karthikeya – but he is also, through his dancing, a practitioner of art and grace. In one of the philosophical asides scattered through the book, Mahadevi contemplates that if humans communicated only with their eyes, many arguments would come to a quick end. “Perhaps it is because of this that one’s spirit, wounded by human voices attacking one another and by the burden of meaningful words, longs to be healed and consoled by the sandal paste of these wordless beings’ fluid, affectionate gaze.” Of the languorous movements of a cow named Gaura, she writes, “There is beauty in speed, but not as much beauty as in a slow pace. The speed of an arrow can dazzle the eyes for a moment, but a flower’s slow, circular movement in a gentle breeze is a feast for the eyes.”

Here and elsewhere, it is easy to see what she means when she says that “all my memoirs have sprouted, budded and bloomed from this childhood prose expression”. The elegance of Vanita’s translation notwithstanding, many passages made me yearn to read the Hindi original. (A description of the lustrously white Gaura with her red calf – evoking snow and fire – was originally, as Vanita tells us: “Mata-putra donon nikat rehne par himrashi aur jalte angaarey ka smaran karate thay.”)

**** As someone who has developed a close interest in other life-forms while living in a harsher, less animal-friendly urban environment than Mahadevi did, reading My Family was a source of both envy and fascination for me. My limited interactions with animals in recent years, though centred on a confounding variety of street dogs, has occasionally extended to monkeys, peahens, crows and squirrels. (And rats, which can be very personable creatures. When I take a freshly trapped rat to a nearby park and let it out, I now look for the particular way in which it leaps out of the opened trap, whether it scuttles off in a blind panic without trying to take stock of its new environment, or whether it pauses for a bit, looks around contemplatively – there I go “anthropomorphising” – and then picks the wisest exit strategy.) Mahadevi’s pieces felt like motivation to observe even more closely, within the constraints of my environment.

As someone who has developed a close interest in other life-forms while living in a harsher, less animal-friendly urban environment than Mahadevi did, reading My Family was a source of both envy and fascination for me. My limited interactions with animals in recent years, though centred on a confounding variety of street dogs, has occasionally extended to monkeys, peahens, crows and squirrels. (And rats, which can be very personable creatures. When I take a freshly trapped rat to a nearby park and let it out, I now look for the particular way in which it leaps out of the opened trap, whether it scuttles off in a blind panic without trying to take stock of its new environment, or whether it pauses for a bit, looks around contemplatively – there I go “anthropomorphising” – and then picks the wisest exit strategy.) Mahadevi’s pieces felt like motivation to observe even more closely, within the constraints of my environment.

Reading this book, I was also reminded of the title of a 2008 essay by Vandana Singh, “The Creatures We Don’t See: Thoughts on the Animal Other.” Singh writes:

“It seemed as though humans were so intensely obsessed with their own concerns that they didn’t ‘see’ other life-forms, let alone recognize their significance […] Just as being blind to the oppression of women creates conditions where this oppression continues unchecked, being unable to ‘see’ other creatures allows us to go about blindly and stupidly destroying the ecosystems on which we depend...To not recognise the connection between us and other species is to suffer from a sort of mass autism.”

In this light it is telling that many of Mahadevi’s biographers and critics failed to “see” the creatures she wrote about, or the attentiveness with which she wrote about them.

As Ruth Vanita notes in her introduction, these pieces record a kind of Indian urban modernity that encompasses ways of interacting with nature that are now gradually disappearing. It’s too much to hope for a meaningful return to that idyllic world (I certainly wouldn’t be optimistic about it, given my daily encounters with “respected” members of my neighbourhood who seem to view most animals and birds as pests that should be removed from their sight), but a book like this is a reminder of what such a world could look like, and how much we have lost on the road to “development”. It is also a nourishing look – as valuable as a good autobiography – into the mind of an important writer who came to view all life as part of a single shared consciousness.

[My earlier Scroll pieces are here. And a related post: wolves, humans, colony dogs]

No comments:

Post a Comment