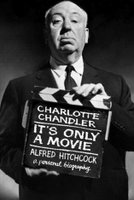

Normally I consider book-jacket blurbs to be of worth only for their comic value, but this one caught my attention immediately. “The best book ever written about my father!” exults Patricia Hitchcock on the cover of Charlotte Chandler’s It’s Only a Movie, subtitled Alfred Hitchcock: A Personal Biography.

Normally I consider book-jacket blurbs to be of worth only for their comic value, but this one caught my attention immediately. “The best book ever written about my father!” exults Patricia Hitchcock on the cover of Charlotte Chandler’s It’s Only a Movie, subtitled Alfred Hitchcock: A Personal Biography.I’ve read more books on Hitchcock and his films than on any other single subject. I used to be obsessed with the man’s work (by “used to be” I don’t mean I hold him in less regard today, just that I reached a saturation point and moved on to other things). His films spoke to me more directly than those made by other directors who were more acclaimed for the depth and seriousness of their work (but who, ironically, took the easy way out by keeping their themes and ideas on open display – unlike Hitch, who kept his buried within the narrative structures of his films). Hitchcock’s movies gave me a more immediate understanding of the countless little ways in which we deceive and manipulate each other, and ourselves. They also taught me that a work of art doesn’t have to contain meaning at only the most obvious, superficial level for it to be profound.

Like I said, there was a point where I could no longer bear to look at another book on Hitchcock; my instinctive response to a new biography was “ho-hum, what’s left to be said”. But Chandler’s book is very entertaining, insightful and notably different from most other indepth studies. Firstly, she doesn’t discuss Hitchcock’s films at great length, or try to bring a critical perspective to them (it’s clear that she doesn’t think of herself as a film critic, or maybe she just feels that enough dissertations have already been written on these movies). Instead she follows a set format, moving chronologically from one film to the next, providing a short synopsis and – this is the meat of her book – recording quotes and observations from cast and crew members involved with each film (including Hitchcock himself on occasion). No attempt is made at linking chapters thematically.

This makes It’s Only a Movie sound tedious and lazily strung together, but that isn’t the case at all. Chandler’s approach may seem unstructured and messy at first but gradually, as the quotes add up and we move through a career that spanned over 50 years from the silent era to the late 1970s, a portrait of the man begins to emerge. Importantly, it isn’t a definitive portrait but a kaleidoscopic one, for Hitchcock was many things to many people and by speaking to so many respondents Chandler has brought out different sides of his personality.

Most actors, for instance, had ambivalent (if not downright unpleasant) memories of working with Hitchcock - not surprising given his famous dismissal of performers as “cattle”, or chess pieces to be moved around. His great visual sense meant he had the entire film ready in his mind before a single scene had been shot (he prided himself on never having to look into the camera) – but this could naturally be frustrating for actors who might want to improvise a little while shooting. “People say Hitch wasn’t spontaneous,” James Stewart once said, “but he was. It’s just that all of his spontaneity occurred on paper before he got to the set!” Tippi Hedren, who starred in The Birds and Marnie, still has bad memories. “He was more careful about how the birds were treated than about me,” she said. “I was just there to be pecked.”

But a few performers (not just his favourite blondes) also remember him as uncommonly generous and non-intrusive. “He wasn’t a backseat actor,” recalls Hume Cronym. “He expected us to know our jobs. I don’t consider that being unconcerned with your actors.” And during the intense scene between Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) and Detective Arbogast (Martin Balsam) in Psycho, the two Method actors were able to persuade the orthodox director to ditch his original storyboard to allow a scene that would permit overlapping dialogue.

Some things about Hitchcock are beyond dispute though – his talent for macabre practical jokes (like stepping into a crowded elevator with a friend and loudly saying “I hope you got all the blood off the knife” just as they had reached their floor and were about to get off). Or the wordgames that would confuse his crew when he gave them instructions: “Dog’s feet” was his code for “pause” (“Dog’s feet” = “paws”) and “don’t come a pig’s tail” translated meant “don’t come twirly” = “don’t come too early”.

Then there were his ribald little jokes, all the more effective for being delivered in a deadpan tone, and because they were so at odds with his very Brit properness. “There’s hills in them thar gold!” he whispered to Grace Kelly once; she was wearing a low-cut gold gown. “I found it especially amusing,” she recalled, “because Hitch was always so decorous and dignified with me.” He also had a habit of saying, “Call me Hitch, without a cock” to people when he wanted them to be informal with him. This last bit is almost a refrain in Chandler’s book, so much so that after a while it stops being silly and becomes endearing.

The most notable thing about this book is the sheer number of people Chandler has spoken to. A professional biographist (she’s written books on Billy Wilder, Groucho Marx and Federico Fellini before this), her style of working is remarkable – it appears that she either has a photographic memory or takes notes assiduously every time she happens to meet someone who might have a useful anecdote to relate. She did of course interview many respondents especially for this project, but many quotes are drawn from meetings with people from several decades earlier; this book is full of sentences like “A few years ago Gregory Peck told me that when he was working with Hitch…” or “I met Sir Michael Redgrave at his last birthday party and he mentioned that…”, all served up in the most offhand way. (How does this woman know so many people, I kept wondering. I couldn’t find much about her on the Internet.) But some of the most rewarding interviews are with the bit-players: with Georgine Darcy, for instance, who played the tiny role of the bouncy “Miss Torso”, one of the many people James Stewart looks at through his binoculars in Rear Window.

I can’t quite agree with the Patricia Hitchcock blurb, but this is certainly the cosiest and most personal Hitchcock book I’ve yet read. Which is just the kind of relief we need now from the surfeit of tomes that over-analyse and dissect his movies (though I love those too!). As Hitch would often say when people started taking things too seriously, “It’s only a moo-vie.” It’s another matter that he never believed it himself.

(Another post coming up soon, about other books on Hitchcock.)

I really liked your blog. Especially the reviews. Really great work.

ReplyDeleteTan

(http://tangrowsup.rediffblogs.com)

the serendipitousness of these posts sometimes amazes me. there's a hitchcock retro at the hyfic, alas none from his silent era. the ones i really want to see again are suspicion and strangers on a train, but those aren't on the list.

ReplyDeletestill, 39 steps, rope (which i've only ever seen on video), birds, rear window, vertigo, the man who (jamers stewart version)...*sighs with pleasure*

will look out for the book.

My only quarrel with Hitchcock's 39 Steps, is the ending. He changed the original ending as in John Buchan's book into the silly guy-on-the-stage thing. Quite spoilt the book for me.

ReplyDeleteSo which is your favourite book on Hitchcock ?

ReplyDeleteI haven't read much but I find Freudian psycho-analysis, which almost all Hitchcock critics inevitably resort to, very boring. They hardly ever tell anything interesting about human nature or improve our understanding of the intricacies of hitchcock's art. Mostly It all reads like empty academic speculations.

Saba: oh I thought the guy-on-the-stage bit was superb (incidentally Hitch was very pleased with it himself - especially with the idea of someone who would rather put his life in danger than say he didn't know the answer to a question).

ReplyDeleteAlok: my favourites are Robin Wood's Hitchcock's Films Revisited and Peter Conrad's The Hitchcock Murders, both of which I'll blog about soon. But these are extremely personal books, written by people who admit to having been very particularly affected by Hitchcock's movies at an early age (like I was).

Yes there has been plenty of over-analysis, but I think that's representative of how deeply Hitchcock movies affect certain people, who then want to write about them at great length, defend them from critics who condescend on the genre. Frankly, given the short shrift the man got from critics during his own lifetime, I don't think the analysis is out of order, even if it gets a bit extreme at times.

Tan: thanks.

"serendipitousness" says space bar. how ridicularitesque!

ReplyDeleteCongrats jabby! It has been confirmed from independent sources that you are a humanitarian after all :)

ReplyDeleteWhat I particularly like about this book also was how often he gave credit to his wife Alma. I haven't seen that in many books on him - but then I haven't read as many books on Hitchcock as I would've liked to. Plus I had no idea how conscious he was about his weight - such a contrast to the perfect looking characters in his movies....

ReplyDelete