Nyagrodha: The Ficus Chronicles came so enthusiastically recommended by the chaps at Penguin that I was prepared for disappointment. But any misgivings vanished a couple of chapters into the book. There was nothing too special about the first few pages, wherein three unhappy, runaway children wander deep into the woods together and come to a large banyan tree “that shakes down stories” when you call out its ancient name, Nyagrodha. However, the whole thing comes alive when Hanumanta the Langoor starts telling the children tales about the forest and its inhabitants.

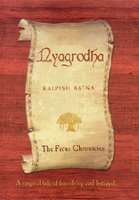

Nyagrodha: The Ficus Chronicles came so enthusiastically recommended by the chaps at Penguin that I was prepared for disappointment. But any misgivings vanished a couple of chapters into the book. There was nothing too special about the first few pages, wherein three unhappy, runaway children wander deep into the woods together and come to a large banyan tree “that shakes down stories” when you call out its ancient name, Nyagrodha. However, the whole thing comes alive when Hanumanta the Langoor starts telling the children tales about the forest and its inhabitants. This is a wonderfully imaginative retelling of the Panchatantra stories that many people of my generation first came across in the Amar Chitra Katha comics. Nyagrodha is coauthored by Kalpana Swaminathan and Ishrat Syed (who use the pseudonym Kalpish Ratna for their collaborative writings), and their framing device is an interesting one. What the authors have done here is to use one story – about Simha the young lion king, his friend Jeev the bull, and two crafty jackals Charak and Tarak, who conspire to turn the two against each other – as the anchoring narrative and to build the Panchatantra tales around it. The way this typically works is: one animal tells another a story in order to illustrate a point (about friendship and betrayal, for instance, or the importance of counselors, or how the weak can overcome the strong).

In places, the structure gets delightfully complicated. Sometimes the creatures in the stories-within-the-stories tell each other impromptu stories in turn, and so it goes – until the narrative approximates the Tree of Stories itself, with its gnarled roots and entwined branches. Interspersed with the text are charming little illustrations of the various creatures and of elements from each story.

But best of all is the authors’ treatment of the Panchatantra tales. They’ve spruced up the language, made it snappier and more irreverent. Some stories are presented in the form of clever little rhymes, the characters’ names are changed (a goat becomes Roghan Josh, a sweet-talking jackal is named Jalebi, an acid-tongued crow is Karela) and there’s plenty of neat wordplay (an astronomer owl discovers a red star and names it paan cheent, which translates into English as “betel juice” – but scientists will naturally want to spell it in a way that makes it look more learned, hence Betelgeuse!).

Revisionism has its own little snares; it’s easy to get carried away by your own cleverness and disregard the spirit of the original story. So it’s important that Swaminathan and Syed have retained the gist of the tales – their delicate humour, their ability to trade in morals without being cloyingly moralistic. I especially enjoyed the way the title of the story “The Nature of the Beast” comments not just on animal behaviour but on human whimsies as well. And the smartness of the exchanges between Jenny and Bosco Braganza, a pair of kingfishers whose eggs keep getting smashed by the wicked ocean.

There are also tongue-in-cheek asides about how seriously human beings take themselves. This dialogue between Simha and Jeev, for instance:

“What are they like? Humans?”

“Nice. But limited.”

“Limited to what?”

“When a thing is uncomfortable, they prefer not to think about it. They invent an explanation that makes them more comfortable.”

“For instance?”

“Take the constellations. You’d think they’d be comfortable knowing there was a lion twinkling at them from the sky? Or a bull, for that matter? Not to mention a ram, a crab and a fish! But they can’t bear it. So they draw complicated pictures to tell themselves it’s all imaginary.”

“A stupid race,” Simha said dismissively.

The outermost story in this book – the one about the three children Aman, Lily and Vicky – is a little weak; I couldn’t work up much interest in their personal problems, which are sketchily dealt with anyway. The effort to make the Panchatantra tales relevant to youngsters who have serious real-world issues to deal with (parents getting divorced, the insecurity of moving to an unfamiliar country, the inadvertent betraying of a friend) becomes self-conscious in places. (This kind of thing was more successfully done in Swaminathan’s Ambrosia for Afters, where the Red Riding Hood tale was placed in the context of the sexual abuse of a young girl.) But fortunately the animals hold the stage for most part, and they make this one of the most enjoyable books you’ll read in a long while.

Note: Nyagrodha is not meant for very young children. Some of the content, like I mentioned, is clearly targeted at mature readers, words like “sybaritic”, “diaphanous” and “prescience” are scattered through the text, and there are some scary passages (e.g. a reference to a tigress eating her prey’s eyes for dessert – “popping them like grapes”). If I worked at Delhi Times I’d say something fancy like “Get this one for the tiny tots and for the child in you”. Instead I’ll make do with “get this just for yourself and don’t lend it to anyone, including your own children”.

The Red Riding Hood tale was about sexual abuse to begin with, wasn't it? A cautionary tale to young girls etc. Perrault's explicitly sexual original is supposed to have been edited down for general consumption.

ReplyDeleteI'm wary of retellings; the Amar Chitra Kathas too precious, perhaps.

Another nice review. I read and lurk and lurk and read, and sometimes post. Thanks for the warning--don't know if I want to introduce eye-popping tigresses to my two and a half year old yet. Sounds like the narrative frame was unnecessary? Isn't it a bit redundant given that the animals in Panchatantra are half way human anyway?

ReplyDeleteWarya: true, but in the book I mentioned the Red Riding Hood tale was very neatly used to illuminate one of the characters' stories. Also, the revisionism was in the form of the suggestion that young girls aren't only threatened by abstract wolf-figures from the outside world; sometimes the danger is in their own homes.

ReplyDeleteThe Grimm stories have been strongly edited down too.

the Amar Chitra Kathas too precious, perhaps

Well, they were aimed at a very young readership - they certainly worked fine for me when I was 6!

Chandi: thanks. I think the narrative frame was a way of giving children characters they could immediately relate to.

this sounds interesting...

ReplyDeleteI have always thought that our mytholgoies and fairy tales had great potential for subversion and revisionism. there are not many examples of that happening though...

yes, shame about the constant editing. you know, i have a friend who's doing her phd on the tropes of sexuality in the grimm brothers' fairy tales, and how different translations and edited versions over the years subtly or overtly alter sexual content to better suit a cultural sensibility or time. quite interesting, although pretty soon every rock starts to look like a glistening red apple.

ReplyDeletethey certainly worked fine for me when I was 6!

heh. they certainly work fine when i'm 24.

very interesting take on the Panchantantra stories but yes,i'm generally quite skeptical 'bout such books.

ReplyDelete@warya

check this one Politically Correct Bedtime Stories

I have no doubt Nyagrodha is an absorbing and enchantingly written book, but having recently done a story on children's lit in India, I can't help wishing we could go a little beyond myths/fairy tales/animal stories/fables, no matter how cleverly and refreshingly told or retold.

ReplyDeleteI also have no doubt that most of these stories have resonances in the modern world etc, but could we have somebody write something about the REAL worlds of REAL children, please? A story that has no fantastic characters, one that does not use elements from myths -- even subversively? Is that really so impossible?

JAS is killing my comments, all I've done is to point out that 'the story within a story narrative' structure was part of the original Panchatantra.

ReplyDeleteAnon: tha-a-a-tt's more like it. Stick to the point please. The reason for the earlier comments being killed was the personal abuse directed at Hash and me.

ReplyDeleteYes, the story-within-a-story format is from the Panchatantra, but it's done in a more complex way here.

Jai - Have you read The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter?

ReplyDeleteWarya's friend might like this too, except I assume she's already read it.

I *love* gory not-for-kiddie books, my faves are edward gorey, tom baker, and not surprisingly tim burton does some excellent ones too! this other guy called jhonen vasquez is also quite psycho..but a bit excessively goth. possibly had a crush on poppy z brite in his early teens...

ReplyDeleteI thought you'd be interested, particularly the comment about narrative stucture.

ReplyDeletehttp://www.mumbaimirror.com/nmirror/mmpaper.asp?sectid=18&articleid=6182006234036437618200623377234

Is this book not following in the lines of the books "Chronicles of Narnia" by CS Lewis

ReplyDeleteWhat the authors have done here is to use one story ... build the Panchatantra tales around it.

ReplyDeleteWait a sec! You mean to say that the original Panchatantra is a "loose collection of tales" and the authors of Nyagarodha have managed to string them together. Sorry to disappoint, but that's exactly what the "original" (or whatever that's been handed down across generations and recorded in the early 2nd millenium AD) Panchatantra is all about. Right down to the story of the lion and the jackals. Again, the story within a story technique is also inherent in Panchatantra. And finally, though the choice of names for the characters may be original, that's not to say that Panchatantra is devoid of wordplay --- perhaps the beauty of the book of tales lies in the subtle wordplay on name of characters, places etc.