But back to The White Diamond, a documentary in which Herzog (who was 63 years old at the time of filming this) introduces us to a researcher, Graham Dorrington, and the airship using which he hopes to sail over the rainforests of Guyana to study the fauna of this impermeable terrain. A stunning prologue gives us the early history of zeppelins and the expectations for inter-continental travel that ended with the Hindenberg tragedy. We then meet Dorrington and learn about his childhood obsession with rockets (“Explain to us what happened to your hand,” says an off-camera Herzog in a deadpan voice, as Dorrington holds up his hand to show us that two fingers are missing). We learn, too, about a catastrophe that befell the researcher 10 years earlier - an accident during a previous airship test, in which his cinematographer was killed, and which brings an added edge and purpose to his present mission. And as the film progresses, we get stunning visuals of the imperious Kaieteur Falls and the largely uncharted landscapes surrounding them, even as wistful comic relief is provided by Mark Anthony Yhap, a local man who seems very high on some yet-undiscovered jungle weed; he speaks in aphorisms and talks fondly of his family staying in faraway England, and his pet rooster (not necessarily in that order).

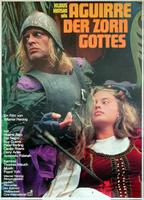

But back to The White Diamond, a documentary in which Herzog (who was 63 years old at the time of filming this) introduces us to a researcher, Graham Dorrington, and the airship using which he hopes to sail over the rainforests of Guyana to study the fauna of this impermeable terrain. A stunning prologue gives us the early history of zeppelins and the expectations for inter-continental travel that ended with the Hindenberg tragedy. We then meet Dorrington and learn about his childhood obsession with rockets (“Explain to us what happened to your hand,” says an off-camera Herzog in a deadpan voice, as Dorrington holds up his hand to show us that two fingers are missing). We learn, too, about a catastrophe that befell the researcher 10 years earlier - an accident during a previous airship test, in which his cinematographer was killed, and which brings an added edge and purpose to his present mission. And as the film progresses, we get stunning visuals of the imperious Kaieteur Falls and the largely uncharted landscapes surrounding them, even as wistful comic relief is provided by Mark Anthony Yhap, a local man who seems very high on some yet-undiscovered jungle weed; he speaks in aphorisms and talks fondly of his family staying in faraway England, and his pet rooster (not necessarily in that order).This is a fine, absorbing film by most standards – but not if you remember some of the towering portrayals of obsession its director once brought to the screen. How Herzog has mellowed with time! Watching The White Diamond, images from the many unforgettable scenes in Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Fitzcarraldo and Nosferatu kept flashing through my mind: films dominated by the extraordinary face of Klaus Kinski, about whom Herzog once reportedly said “The moment I first saw him, I knew it was my destiny to make films and his to act in them.”

That quote encapsulates the Herzog-Kinski relationship so well that it’s completely irrelevant whether it’s true or apocryphal. There’s a whole separate post waiting to be written about the great director-actor pairings in film history, but (with due respect to Kurosawa-Mifune, Von Sternberg-Marlene Dietrich, Bergman-Liv Ullmann, Scorsese-De Niro, Ford-Wayne, Ray-Soumitra and many, many others) this pair is in a class entirely of itself. Though they made only five films together, Kinski’s hypnotically sensual face, his wild, piercing eyes, became the agents for Herzog’s own obsession with pushing the filmmaking process beyond all accepted frontiers.

In Aguirre, Kinski was the 16th century conquistador who leads an expedition through the Peruvian rainforest to find a mythical city of gold. In Fitzcarraldo he was 10 years older, the character he played wore a formal white suit and was less wild to outward appearances; but this was a madman obsessed with the idea of dragging a 360-tonne ship over a mountain in order to realize his dream of building an opera house in the jungle. Famously, Herzog eschewed the use of plastic models or special effects, insisting that this confounding feat be achieved in reality during the shooting of the film – and consequently, the story behind the making of Fitzcarraldo became as famous as the film itself.

Among all the scenes from these films that have been seared into my mind, the final moments of Aguirre are particularly unforgettable. Almost all Aguirre’s men have been cut down by arrows; he turns to see his daughter swaying slowly, realizes she’s mortally wounded. As he holds her body in his arms, hands trailing through her golden hair, one sees that his madness has reached its apotheosis. He now limps about in the desolation (this is a walk Olivier’s Richard III would have been proud of), muttering his grand plans to himself (he would have married his own daughter, founded a race of superior golden beings in the heart of this darkness) and then shouting them out loud to hundreds of little monkeys scampering around the boat. The camera circles the boat a few times, then fades out, leaving him to rule over this chattering little band of subjects.

Among all the scenes from these films that have been seared into my mind, the final moments of Aguirre are particularly unforgettable. Almost all Aguirre’s men have been cut down by arrows; he turns to see his daughter swaying slowly, realizes she’s mortally wounded. As he holds her body in his arms, hands trailing through her golden hair, one sees that his madness has reached its apotheosis. He now limps about in the desolation (this is a walk Olivier’s Richard III would have been proud of), muttering his grand plans to himself (he would have married his own daughter, founded a race of superior golden beings in the heart of this darkness) and then shouting them out loud to hundreds of little monkeys scampering around the boat. The camera circles the boat a few times, then fades out, leaving him to rule over this chattering little band of subjects.In comparison to the passion of these movies, The White Diamond seems a trifle. Even the researcher Dorrington’s long monologue, in which he relates in painful detail the death of his cinematographer friend 10 years earlier, is flat, heavy-handed and vaguely gratuitous. (Dorrington himself has an unfortunately goofy expression in many of his scenes – agreed, he isn’t a professional actor, let alone a Kinski, but this does reduce the film’s dramatic impact.)

Maybe I’m being unreasonable in judging Werner Herzog by the standards he set 30 years ago – maybe he should be allowed to be quieter, more reflective, in his old age. But then I recall Aguirre, Fitzcarraldo, the vampire Nosferatu, and I think: Quiet? Mellow? Herzog? No way – leave the monkey kingdoms to lesser mortals.

P.S. I strongly recommend a superb essay titled “Rats”, published in Granta’s issue on Film a few months ago, written by a Dutchman named Maarten ‘t Hart, who was hired as rat-trainer for Herzog’s Nosferatu in 1979. The essay is fascinating because the author, by his own admission, isn’t a film-lover and is more concerned throughout with the cruelty meted out to his beloved animals – and yet his description of his experience provides one of the clearest insights I’ve ever seen of the attraction held by the filmmaking process. It’s also an invaluable look at Herzog’s dictatorial working style.

P.P.S. Interesting interview of Herzog by Roger Ebert here.

Update: don't miss this post by Falstaff, about Herzog's documentary Grizzly Man.

Great post. Makes me want to run to this video library near MG Road which had a DVD of Aguirre.

ReplyDeleteI actually think it's rather fascinating how Herzog has managed to metamorph into this quietly restrained documentary maker from what he used to be 30 years ago. (check out, if you can, his latest - Grizzly Man - which is fascinating at least partly because of the way Herzog manages to be both decisive and unobtrusive). It's not a transformation one could have imagined easily.

ReplyDeletelong time reader. first time posting. if i had to pick a scene from aguirre which will stay with me forever, it is precisely the one you described. much respect to both men. if you are interested in more on the herzog/kinski chemistry, see the documentary "my best fiend". oh, and wonderful blog. keep writing.

ReplyDeleteIt's a little unfair to compare documentaries with full length feature films even if they explore the same themes. And I don't think Herzog has mellowed at all with time...the depiction of obsession in Grizzly Bear is quite on the same level as in Aguirre or Fitzcarraldo if not even better (perhaps because it is a true story with real footage)

ReplyDeleteHaven't seen any other of Herzog documentaries. It's such a shame, they are so difficult to find. they get limtied screenings and dvd's are difficult to find.

I have been searching for Kinski's autobiography too for so long but no luck.

Read this hilarious review if any one is interested.

"Herzog is a miserable, hateful, malevolent, avaricious, money-hungry, nasty, sadistic, treacherous, blackmailing, cowardly, thoroughly dishonest creep. His so-called 'talent' consists of nothing but tormenting helpless creatures and, if necessary, torturing them to death or simply murdering them. ... Every scene, every angle, every shot is determined by me. ... I can at least partly save the movie from being wrecked by Herzog's bungling,"

-Klaus Kinski

hahaha ;)

Alok: agreed, it's unfair to compare features and docus. But by that same token, why should something automatically be regarded a better study of obsession just because it's a true story with real footage? Personally speaking, I thought Kinski's face in those fictional films said volumes more than any "real" footage ever could.

ReplyDeletei remember that granta article. the author was described by herzog as a sheet anchor or some such dutch word. the author starts out admiring herzog for his attention to detail and ends up quitting the job for what can probably be construed as the very same reason.

ReplyDeletewhich begs the question: do film makers still have to go to extreme lengths in order that their films look realistic? can the question jai raises about docus and features be extended to 'real' images vs computer graphics. think its relevant, because during the shoot of nosferatu apparently thousands of rats died. Hart describes it as the biggest scene of cannibalism ever witnessed by him(13k rats crazed by hunger and thirst after having travelled from hungary to germany over three days with no food and water started picking on the weaker ones), and by the way he describes it, it probably was the biggest ever.

rather disturbing... and am not even an animal lover

another mindless aside: inteerstingly hart's profileon granta.com mentions his contribution to nosferatu. wonder if he approves of it?

warning: totally facetious comment

ReplyDeletejabberwock this is with reference to your repeated comments on 'true' stories vs imagined ones...

was out for the usual smoke n chai break in between staring at spreadsheets and was reminded of something rushdie wrote in 'haroon and the sea of stories'. dont remember which one, but one of the characters asks: "What's the use of stories that aren't even true?"

i know the context is different, but couldnt resist this dig ;)

Truth in cinema? Hmmmm.

ReplyDeleteYou have heard of Minnesota Declaration or "ecstatic truth"?

here and here

Tridib, you found the Aguirre DVD? Really? Let us go then, you and I...

ReplyDeleteJai, great post. Has aroused my interest in Herzog's films.

Herzog...II saw him first time in Julien-donkey boy. Haven't seen nosferatu though....

ReplyDeleteyour blog is very nice.