Tuesday, January 31, 2006

First lines

“We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold” – Hunter S Thompson, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (Wicked understatement, given what is to follow)

“As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect” – The Metamorphosis, Kafka (No understatement here, pretty much sums up the situation)

“When the phone rang I was in the kitchen, boiling a potful of spaghetti and whistling along to an FM broadcast of the overture to Rossini’s The Thieving Magpie, which has to be the perfect music for cooking pasta” - The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, Haruki Murakami

“My name is Charles Highway, though you wouldn’t think it to look at me” - The Rachel Papers, Martin Amis

“I get the willies when I see closed doors” - Something Happened, Joseph Heller

And some classics from Poe:

“There are certain themes of which the interest is all-absorbing, but which are too entirely horrible for the purposes of legitimate fiction” – The Premature Burial

“For the most wild yet most homely narrative which I am about to pen, I neither expect nor solicit belief” – The Black Cat

“During the whole of a dull, dark and soundless day in the autumn of the year, when the clouds hung oppressively low in the heavens, I had been passing alone, on horseback, through a singularly dreary tract of country, and at length found myself, as the shades of the evening drew on, within view of the melancholy House of Usher” – The Fall of the House of Usher

Poe is also responsible for one of my favourite last lines, this one from The Facts in the Case of M Valdemar:

“Upon the bed, before that whole company, there lay a nearly liquid mass of loathsome – of detestable putrescence.” (I love the shocked conservatism Poe brings to phrases like "too entirely horrible" and "detestable putrescence" - you know he relishes the macabre but he keeps his enjoyment hidden beneath a layer of Victorian propriety.)

Zillions more I’m sure, in both categories. Name your own.

Read this review

Chandrahas has a superb, scathing review of Rang de Basanti up on the Middle Stage. Interestingly, his take is as far as it’s possible to get from that of most other reviewers, who have been praising the film to the skies:

“In almost two decades of watching Bollywood productions I have never come across such preposterous drivel as that served up in the second half of this film…The worst thing about Rang De Basanti is that not only does it sloppily promote the idea that violence is fine as long as you are persuaded that the cause is right, it uses an absurd parallel from history to legitimise it, and at every stage superimposes the frame of history upon the action.”

Of course, whether one likes or dislikes a film is secondary (I haven’t seen Rang de Basanti yet and so have no opinion on it); what matters is that the review should be honest and well-argued. This is the kind of passionate film writing I wish there was more of in India, and it makes me want to get back to movie-reviewing myself.

Read the full thing. And Uma has a not dissimilar take on the second half of the film, here.Monday, January 30, 2006

Last notes on the fest: Hari Kunzru, Shobhaa De

- Predictably, the largest crowds showed up for the Shobhaa De reading. Watching the level of audience participation at events like these really does give food for thought to those of us who are snobbish about certain kinds of writers. When De read out wry passages from her books, many shoulders could be seen convulsing with laughter; college girls exchanged excited looks whenever she said anything mildly entertaining, this was clearly a high point in their lives. (One of them stood up and gushed "Ma'am, for me you are the epitome of life and feminism!") A young boy said her very presence made men feel "humble", admitting when asked that he felt so himself. An elderly man called her column "uncharitable, liberal and sarcastic". De nicely played off her image as an attention-soaker too: "A little reaction please!" she exclaimed in mock-indignation when no one clapped after she'd finished a reading. ("We were too breathtaken to react, ma'am!" a front-bencher stammered apologetically.)

- Predictably, the largest crowds showed up for the Shobhaa De reading. Watching the level of audience participation at events like these really does give food for thought to those of us who are snobbish about certain kinds of writers. When De read out wry passages from her books, many shoulders could be seen convulsing with laughter; college girls exchanged excited looks whenever she said anything mildly entertaining, this was clearly a high point in their lives. (One of them stood up and gushed "Ma'am, for me you are the epitome of life and feminism!") A young boy said her very presence made men feel "humble", admitting when asked that he felt so himself. An elderly man called her column "uncharitable, liberal and sarcastic". De nicely played off her image as an attention-soaker too: "A little reaction please!" she exclaimed in mock-indignation when no one clapped after she'd finished a reading. ("We were too breathtaken to react, ma'am!" a front-bencher stammered apologetically.)- De also drew the biggest applause when she remarked that on a daily basis she encountered at least four or five exceptional women doing exceptional things – "but I don't see an equivalent number of exceptional men. Where are you, guys? Join us at the winning goal (post?)!" Rah rah.

- Hari Kunzru read from The Impressionist, a passage where Pran Nath manages to dissemble as an Englishman because of his unusual skin colour. As a half-Indian who's grown up in the UK himself, Kunzru talked about how he often gets slotted by critics and journalists. "It feels odd when people say oh you're so lucky, you have the best of two cultures – like I've been handed two goodie-bags. But no one experiences culture like that: it's more like the sum of everything that makes me what I am."

- "I'd like to write a futuristic book," he said, mentioning his fascination with the ways in which human beings interact with the technology of their own making. "We treat the Internet more as a moody living organism than as a cold machine. It's like discussing the weather, we say things like 'oh, it looks like it's going to be slow today'."

I was a little put off by Kunzru's condescending remark that the kind of sci-fi he'd like to write is "literary sci-fi, like Margaret Atwood does for instance – not the kind of sci-fi where you have these strange characters in an invented setting" – here Kunzru waved his hands about in a less-than-convincing attempt to evoke the kind of "stereotypical sci-fi" he was talking about.

Had a decent chat with him later though. I find his treatment of the theme of lack of communication (in the brilliant short stories he's written for Mute magazine, for instance) quite compelling, and I wanted to know when he's going to get back to short fiction. "Probably not too soon," Kunzru said. "I'm a lazy writer and I can't write short stories side by side with a novel – which is what I'm working on now." He thinks Jaipur is a wonderful place for literary events of this sort – "the right atmosphere, enthusiastic people and a lot of venues scattered over a relatively small area".

(My review of Kunzru's Noise here.)

- One of the charms of the fest for me was that it wasn't a lavish, media-infested event with journos crawling about the place like maggots on rotting meat. What this translated into was small but enthusiastic audiences and a merciful lack of cameras and microphones - meaning it was possible for the writers to mingle with the crowd and discuss their work relaxedly rather than switch into P3P mode every now and again. This gave the festival a flavour that's usually missing from the ostentatious book launches/readings held in Delhi. I've become fed up of those types of events and was quite happy not to run into a single other lit-journo at this one.

Sunday, January 29, 2006

Fed up

Aishwarya: Good grief!! This is unnerving.

Jai: Yes, a little like watching a robot short-circuit.

A mean-minded, cynical observer (and of course I’m not that person) might think there was something calculated about Federer’s tearful display – that it was put on, at just the right time, for the benefit of those who accuse him of being expressionless hence mechanical, and of undermining the sport’s human element. In my limitless munificence, however, I’m inclined to think it was genuine emotion – perhaps brought on in part by the presence of the legendary Rod Laver, whose achievement of winning all the Grand Slams in a year Federer will now hope to emulate.

Of course it isn’t fair to call Federer robotic – he’s beautiful to watch when he’s on the court, there’s nothing mechanical about his actual play. But the predictability of his matches– that familiar sinking feeling as you realise the script has been pre-written and there’s only going to be one result – has become depressing. Despite what I said in this post a few months ago, this sort of thing can’t be good for the sport.

It must be tough to be Federer – that is, once you’ve taken away the millions of dollars, the dozens of titles and the adulation. I often wonder how he must feel when a match ends and he has to walk to the net to shake hands with his disgraced opponent. What does he say to the other guy, especially when it’s someone he’s beaten the last six matches they played? He can’t say “Well played” or “You gave me a scare back then” because that would be an obvious lie and the other chap might spit in his eye. And because Federer’s a nice guy he can’t even be truthful and say to Lleyton Hewitt or Andy Roddick, “Look, I’m a thousand times better than you are at the thing you do best, and I’ve just made you look like an idiot again in front of millions of people.” That would be out of character. So he just looks down and mumbles something, and for that brief moment looks like he’d be happy for the ground to open and swallow him up – an odd reaction from a man who’s just won a tennis match, possibly a title.

Anyway, here’s hoping Nadal or Safin or Nalbandian or someone gives him a decent challenge soon. The first two sets of today’s final were at least enjoyable because one got to see him hurried - running around a lot, struggling to reach the ball, even missing it a few times. Would be good to see more of that this coming year, regardless of the result.

P.S. Also good to see Mahesh Bhupathi winning his 10th Grand Slam title. Watched a lot of tennis today.

Friday, January 27, 2006

RJ-ing means never having to say you're sorry

"I don’t think there can be a single human being walking the face of the earth who didn’t feel boundless love oozing out of every pore of their bodies when they first saw this film."

Now I’m broadminded enough to accept that I must share the planet with people who liked that film. But did that sentence really need "single human being", "face of the earth", "boundless love", "oozing" and "pore of their bodies" all packed into it? Radio jockeys, I tell you. I’m going to have an accident one of these days just because it’s dangerous to take notes while driving.

Desicritics...

I haven't been able to contribute anything yet, but hope to soon. Will probably start by cross-posting some of the stuff I write here since there won't be enough time to write completely fresh material.

(More about Desicritics here.)

Thursday, January 26, 2006

Links

I'll continue updating too, but probably won't be able to post until tomorrow. Lots of work. My posts so far are here, here and here.

Meanwhile, young Chandrahas is back to lit-blogging too, though not about the fest: check out his latest posts, this one on José Saramago and this one on the Hungarian poet Attila Jozsef (I love the headline, it's so Chandrahas - sorry, Hash!).

Wednesday, January 25, 2006

Notes from the fest: Anita Roy, storytelling for children

“Having fun is crucial” was the central point of Roy’s talk as she recounted the conservatism of 1950s America (“which has parallels with contemporary India, and the questions being raised about what kids should read”) and the emergence of Theodore Geisel/Dr Seuss, whose books (with their brilliant play on the sound and rhythm of words) brought about a revolution in children’s literature. “Let’s hope a similar leap of imagination occurs in India too,” she said. “There are so many new issues that children are dealing with in today’s world and there’s potential for literature that deals with these issues in imaginative and exciting ways. We need to move beyond the Enid Blytons and the Panchatantra now.”

Established stories must be played around with and retold in different ways, said Roy as she related a personal conflict of interest. “As a publisher I have to deal with issues of control and copyright and be straitlaced about certain things. But as a person and as a mother I believe stories belong to everyone once they’re in the public domain – you should be able to change an ending if you don’t like it, or add your own bits.”

As Roy gave some examples of Dr Seuss’s creations (like the Quink who drinks pink ink), there were predictable hints of disgruntlement among sections of the audience. “Shouldn’t children be taught to distinguish between fantasy and reality?” asked one lady, citing the example of a couple of kids who had thrown themselves off rooftops after watching the TV serial Shaktimaan (presumably pretending to be the superhero, or expecting him to come to their rescue). “Of course they should,” retorted Roy, “but that’s where the teacher/parent’s role as an interpreter is important. And that’s why telling stories to children firsthand is a better alternative anyway – television is a passive medium and too many parents leave their kids to watch TV by themselves, so they have no one to explain things to them.”

(Privately, Roy was less polite about the whole thing. “All of us have grown up with such TV shows,” she said to me later between puffs of her cigarette, “but very few of us go leaping off roofs. You have to think that in the case of children who do those things, there must already be other negative factors at work – lack of parental attention, an unhappy family environment – in the background.”)

Notes from the fest: Vivek Narayanan, performance poetry

There was an element of gimmickry at the start of Vivek Narayanan’s poetry reading – he was sitting among the audience in a corner at the back (something none of us was aware of) and after he was introduced he simply began his recital from there, eventually getting up and moving to the front of the hall. “In recent times I’ve developed this little thing about being anonymous at the start of these readings,” he told me later, “When there are people present who know me, I ask then not to tell others in the audience. It helps me build my performance the way I’d like to.”

“Performance” is the right word – Narayanan didn’t just recite his poems, he acted them out, complete with strong vocal inflexions, some chanting and hand gestures. There was some interesting work in there, including an “ode to prose and prose-writers” (“you take our money/but we love you anyway”), a tribute to Silk Smitha, the south Indian sex symbol who killed herself a few years ago, and a tongue-in-cheek poem about the actor-politician MGR, who had described himself as an angel. But what I found more interesting was the way Narayanan performed them.

I had a rewarding little discussion with him the next day about the concept of performance poetry. He’s been writing poems seriously since he was 13 (he’s 34 now) but he first became interested in performance poetry in a club in San Francisco in the mid-1990s. “However, some of the work there started to veer towards slapstick,” he says, “and I became uncertain about practicing it.” Then, he says, he began listening to rap music. “The rap underground is fascinating. Ten-year-olds living in black districts in the US have a better understanding of rhythm and meter than many self-anointed poets do. It’s no surprise that poets like Derek Walcott and Seamus Heaney have such high regard for rap music.”

Around that time Narayanan also discovered some old recordings of readings by poets. “Did you know that Eliot was the first to record on LP? And that there are still extant recordings of Yeats, Tennyson and Browning performing their work? Edison made those early recordings – maybe he thought he’d be able to make money off them at some point!”

Many of those early recordings, Narayanan says, were very inventive, with the poets paying careful attention to tempo and meter. But subsequently, the idea that poetry reading should be “natural” took over. “As a result, people have become disconnected from one of the essential things about poetry – that its meaning lies as much in the performance as in the words. These days it’s become habitual to simply analyse the words for meaning, thereby turning poetry appreciation into an academic exercise. In actual fact, each line needs to be tested for sound. This is one of the things that differentiates poetry from prose.”

How then do you differentiate poetry from songwriting, I ask, since one of the things we are repeatedly told is that the great modern songwriters – Dylan, Simon, Joni Mitchell – mustn’t be called “poets”; that the music, vocals and words have to be given equal importance in an appreciation of their work. “There’s a fine line,” Narayanan admits, “but you have to think of it as a continuum. Poetry is closer to speech. The same way the writing of a business letter is an exaggerated, formalised branch of prose, songwriting is an extension of poetry.” His own influences include both poets and songwriters: from underground rappers like Talib Kweli, Mos Def and Common to singer-songwriters Bob Marley, Leonard Cohen and Mark Knopfler.

[Narayanan has taught history in South Africa (“while doing research for a PhD I never completed!”) and now coordinates the fellowship programme at Sarai. He has a book of poetry, Universal Beach, coming out in a couple of months. You can read some of his poems on this link.]

Tuesday, January 24, 2006

There and back again

It wouldn’t have been much fun if I’d gone alone though. Nikhil and Chandrahas were great company (excepting this shared character flaw that they are Rahul Dravid fans and wanted to watch highlights of his century at the same time that Indian Idol was on. This is unacceptable). Nikhil is as smart-alecky in real life as in blog meets (though at heart he’s a sweet young lad, not the devil’s advocate he likes to think he is), while Chandrahas – already a reputed lit-blogger, honorary Russian, short-story writer and master of the thoughtful, faraway expression – showed an unforeseen talent for making up wordgames, like the one where you form a never-ending chain out of the names of Pakistani cricketers (Mohamed Yousuf-->Mohammed Akram-->Wasim Akram-->Wasim Raja and so on).

Will blog about the fest in detail later. For now, I’m faced with the terrifying prospect of checking email and Bloglines updates after being away from the Internet for three days. It really is very frightening, especially when one is on many different mailing groups. (Which reminds me – Desicritics, a promising new group blog, is launching very soon, so do keep an eye out for it.)

More soon.

Friday, January 20, 2006

Kiran Desai interview

The most striking, and endearing, thing about Kiran Desai is how laidback she is. Even with an interview being conducted on limited time, it's easy to drift into a free-flowing, non-bookish conversation with her: about the very filling lunch she just had at Swagath (an ill-advised way to start an afternoon that will be spent talking with journalists); about how Delhi's food culture has changed since her childhood days, when the Punjabi-Chinese at Golden Dragon qualified as fine dining. Later, when she marvels at debutant writers getting younger and more publicity-savvy (“isn’t it disgusting!” she stage-whispers in jest), it's possible to forget she's an author herself. She doesn’t go to book parties or publishing events, she says; the thought of writers putting their personal email IDs on their websites makes her wide-eyed.

The most striking, and endearing, thing about Kiran Desai is how laidback she is. Even with an interview being conducted on limited time, it's easy to drift into a free-flowing, non-bookish conversation with her: about the very filling lunch she just had at Swagath (an ill-advised way to start an afternoon that will be spent talking with journalists); about how Delhi's food culture has changed since her childhood days, when the Punjabi-Chinese at Golden Dragon qualified as fine dining. Later, when she marvels at debutant writers getting younger and more publicity-savvy (“isn’t it disgusting!” she stage-whispers in jest), it's possible to forget she's an author herself. She doesn’t go to book parties or publishing events, she says; the thought of writers putting their personal email IDs on their websites makes her wide-eyed.Besides, I never do succeed in wheedling out why it took her seven years to complete a second novel after Hullabaloo in the Guava Orchard (1998) - this in an age when publishers warn authors that there mustn’t be a long gap after the first book. Desai's faraway expression suggests she isn't quite sure herself what she was up to. "I suppose I was working and reworking the second book a lot," she says vaguely.

But that she isn’t casual or laidback about her actual writing becomes obvious when we start to talk about this second book, the just-published The Inheritance of Loss. She enthusiastically relates anecdotes, expresses her disappointment that so many characters and incidents didn’t make it to the final draft. “At one point I had something like 1,500 pages of notes,” she says, “and it was a real struggle to hold it all together and then pare it down.”

Set in the mid-1980s in Kalimpong, high in the northeastern Himalayas, The Inheritance of Loss centres on three people and one dog living together in an ancient house named Cho Oyu. There's the embittered, reptilian judge, lost in his chessboard and in his memories: of a youth spent at Cambridge many decades earlier; of humiliation in a foreign land. Staying with him (in this order of affection received) are his beloved dog Mutt and his 17-year-old granddaughter Sai, who was orphaned as a child. The judge's cook, who manages the household, and a few neighbours scattered around the area, round off the cast. As the story unfolds, insurgency is growing in the region: the Indian Nepalese want their own country or state, a Gorkhaland where they will not be treated as servants; young boys, trying to be men, roam the mountainside looting houses, collecting ammunition. Their predicament is contrasted against that of Indians settled abroad (the cook's son Biju, stumbling from one job to the next in the US, in a humorous parallel narrative).

Reading Inheritance, one initially feels it could have been shorter - with many characters, and a narrative that leaps around in time and space, it occasionally gets unfocussed. But Desai’s descriptions of the things she had to leave out (the back-stories of characters who seem shadowy in the final draft, for instance) are so vivid, it’s possible to wonder instead if a longer version of the book might have been more effective.

Why did she choose Kalimpong as a setting? “I spent parts of my childhood there, at an aunt’s place,” she explains (in a house called Cho Oyu!), “and I wanted to capture what it means to grow up in such a fascinating environment, with such wonderfully disparate people." The first stirrings of insurgency were being felt at the time, she recollects, “but at that age I had no real understanding of the issues involved. I was concerned only with my own world.” Some of this reflects in Sai’s character in the book; the petulance of the lover’s spats between her and Gyan (a young man readying to join the insurgents’ ranks) reminds us that they are essentially children caught in events way over their head. “I wanted to depict how we never really try to understand what life is like for other people.”

Desai was 15 when she left India - she lived in England for a year and has been in the US since then - and it’s tempting to pigeonhole her as another NRI writer obsessed by themes like dislocation (something that certainly runs through Inheritance). In person, however, she comes across as someone who’s never really felt out of place no matter where she’s been. She’s pleasingly unselfconscious about the topic of immigrants, joking (again from the outside, as if she isn’t personally involved) about the various kinds there are: “those who throw up their hands at the difficulties - and, at the other end of the scale, those who are expert at playing the ethnic card, accentuating the character traits they are expected to have, and thereby making a success of their lives”. Like Biju’s worldly-wise friend Saeed Saeed, one of the many characters in Inheritance she would have liked to give a bigger stage to.

She’s so fond of relating stories - about the rodent population in Harlem, for instance, which led to the formation of a “Neighbourhood Rat Committee” - that it’s no surprise when she promises not to dally as much over her next book (possibly a novel set in New York) as she did with this one. “It might make more sense,” she concedes with a laugh, “to spread the stories out over many books, and publish them more frequently!”

Writer’s voice, redux

In blog-related discussions in the past I’ve mentioned how much scope there is for misunderstanding when you know a person only through their writing - hence the phenomenon of readers taking a post dead seriously when it was written in a facetious vein, or extrapolating a rigid, all-encompassing worldview from a single throwaway sentence. Interviewing Desai was similar in a way. I had half-expected to meet a very solemn Indian Author Settled Abroad, keen to pontificate about the plight of people who have no place to call their own. But this was a nice surprise.

(Photo credit: Priyanka Parashar)

Wednesday, January 18, 2006

Broken toothpicks + update

Chandrahas (who didn’t make it to Pakistan after all) and Nikhil will probably come along too. All in all it should be a lot more fun than watching a Test match where 1100 runs are scored for only eight wickets *sniffs and casts resentful gaze at Shamya and Amit*.

Other Hitchcock books: Robin Wood vs Truffaut

The first book about Hitchcock I read was the one that remains most famous to this day – the collection of interviews by Francois Truffaut. I enjoyed it at the time (it was, after all, my initiation into what Hitchcock himself had to say about his movies and the process of making them), but my admiration has dimmed considerably over the years. Though the Truffaut interviews played an important pioneering role in the mid-1960s – a time when few American or British critics would have attempted a serious study of Hitchcock’s work – they are surprisingly lightweight when looked at today, content with discussing only the most superficial aspects of the films.

I remember being disappointed by Satyajit Ray’s patronising attitude to Hitchcock in his review of Truffaut’s book (which formed one of the essays in Our Films, Their Films). Given that Ray was usually such an open-minded, perceptive critic, I was surprised by his bull-headed insistence that the genre Hitchcock chose to work in precluded his being taken seriously as an artist. (What a hollow argument!) But I couldn’t disagree with his central point, which seemed more a criticism of the Truffaut book than a criticism of Hitchcock. “What the book fails to achieve,” wrote Ray, “and in failing defeats Truffaut’s main purpose in writing it, is to raise Hitchcock to the eminence of a profound and serious artist.”

I wonder if Ray ever read some subsequent books which in my opinion did help achieve this: notably Robin Wood’s Hitchcock’s Films Revisited, a very personal examination of the themes and ideas that lie beneath the surface of the seemingly innocuous narratives in many Hitchcock movies. Wood has been accused of over-analysis, of reading things into the films that aren’t obviously there, but his book illustrates a very important point: that a work of art must be judged by what it says to each viewer (or reader, or listener), not by what the artist himself intended (or claims he intended) it to be. Wood repeatedly invokes D H Lawrence’s “Never trust the teller, trust the tale” to remind us that 1) artists are usually not very honest about their work, and 2) even when they intend to be honest, there are inevitably layers in the creative process that they themselves are not consciously aware of.

This is especially relevant in Hitchcock’s case because he was famous for saying facetious things about his own movies, thereby confounding the efforts of his loyalists and defenders (like Truffaut). For instance, expressing his happiness with the commercial success of Psycho, Hitchcock told Truffaut:

“That’s what I’d like you to do – make a picture that would gross millions of dollars throughout the world…you have to design your films just as Shakespeare did his plays – for an audience.”In his review, Ray pounced on this statement, holding it up as an example of Hitchcock’s concern only with the box-office and not with making “serious” cinema. But instead of just taking Hitchcock’s remarks at face value, I wish he had turned to Psycho itself, and seen firsthand what it had to say about the Master’s approach to his art. Here is a film that plays like a great ballet for most of its duration, is thoroughly compelling even on repeat viewings when all its secrets have been uncovered, and yet also makes powerful statements about loneliness, shared guilt and the cruel arbitrariness of life – most importantly, it does all this without once compromising on the demands of its genre (namely that the audience be thrilled, terrified, kept on the edge of their seats). Instead of flamboyantly holding his themes up for the world to see and appreciate (as many “serious” directors do), Hitchcock seamlessly incorporates them into the film’s narrative framework (small example: the scene of Marion’s long car journey, where the voices she hears in her head and the demonic grin on her face foreshadow a far deeper madness to be revealed at the end of the film).

Psycho is one of the most overanalysed movies ever (right up there with Citizen Kane and Un Chien Andalou), but when all the words have been exhausted, each frame of the film carefully dissected, what stays with me is its pure, poetic beauty. It’s a film I can sink myself into endlessly, and Robin Wood’s essay on it is one of the best I’ve ever read (along with the ones written by Danny Peary in Cult Movies 3 and by V F Perkins - no relation to Tony Perkins! - in his excellent analysis of film editing in Film as Film).

Hitchcock’s Films Revisited, by its very nature, won’t appeal to all Hitchcock fans - Wood’s obsession can get stifling at times and it’s my belief that this book will strike a chord in you only if a Hitchcock film got under your skin at a young age. (In Wood’s own case, incidentally, the film in question was Rope: he saw it as a 17-year-old trying to come to terms with his homosexuality, and couldn’t understand why he pathologically identified with the John Dall character Brandon; it was only later that he understood the story’s gay subtext.)

(Next on the list: The Hitchcock Murders by Peter Conrad.)

Monday, January 16, 2006

Of porn and Pasolini: the Palika Bazaar trail

-------

I descend into the labyrinthine underworld that is Palika Bazaar wearing my shabbiest sweatshirt and jeans, face covered by a three-day stubble. “Look the part” was the counsel from experienced friends when they learnt I was going porn-hunting in the interests of journalism. I practice the upward curl on my lips; it makes me look both knowing and lecherous – I think.

I've barely entered the atrium on the upper floor of the famous underground bazaar when a young shop assistant approaches. “Seedies?” he enquires politely, this being how both VCDs and DVDs are referred to here. “Double aur triple hai?” I retort (the “X” is unnecessary in this setting) in what is intended to be a smooth, throwaway tone.

To all intents and purposes the shop was closed, but “double aur triple hai” would have knocked “Open Sesame” out cold in a fight: the shutters are yanked one-third of the way up, I’m escorted inside and back down they go again. The owner is unsuitably avuncular, he wears thick glasses, has a warm, open smile and this starts to feel awkward, like buying condoms from the friendly neighborhood chemist you’ve known since you were a child. But then he opens his mouth to speak. “You want combination, single, Asian, schoolgirl, kitty aunties, frontside, backside, oral, multiple? All varieties available. Full one-and-a-half hour. Rs 150 only.” (Kitty aunties?)

Dozens of discs are on display, the images on their covers leave nothing to the imagination. This isn’t cutesy Playmate of the Year stuff, it’s distressingly biological. They get new titles everyday, I’m told, “the best from around the world, over 500 to choose from”. Soon uncle senses I’m new at this, drops the connoisseur act. “Don’t worry, sabhi films mein sab kuch hai” – this said with a wink and a slight leer (he’s clearly been practicing at home as well). I excuse myself, say I’ll look at other options and return. The same routine is repeated at a dozen other shops, with minor variations in price. At one shop a young girl with a little boy in tow sticks her head under the shutter, asks if they have the Bunty aur Babli soundtrack; she is shooed away.

After half an hour of this I head downstairs to my favourite shop for regular DVD purchases, but my tongue is now on autopilot. “Double aur triple…I mean, world cinema ke titles dikhaana,” I say, as the guy behind the counter starts to shrink back. Like a seven-course meal set before a starving man, the films are spread out – Bresson’s austerity sharing space with Fellini’s flamboyance, silent classics like Griffith’s Floating Blossoms cheek by jowl with Japanese anime; it isn’t uncommon to hear impassioned discussions about Wong Kar-Wai or the French nouvelle wave in this tiny space.

This is one of many shops in Palika that sell the oxymoronic “original copies” – near-perfect prints for a mere Rs 200. The special features on some DVDs don’t work but that’s a small price to pay for immediate access to such a variety of titles – never has the movie buff in Delhi had such choice, not even at the peak of the videocassette era. And the more you frequent a shop, the more latitude you get, starting with a DVD-case for each disc you purchase. (By now I routinely get invited into the little loft above the shop to peruse the catalogue unhurried.)

Cries of “seedy?” rent the air as I clamber towards daylight, my hands full of polythene bags in which Fritz Lang and Ritwik Ghatak nestle alongside “combination triple ex-es”. Palika may not be on the level but it’s a great leveler. From serious film buffs to kitty-aunty admirers, we’ve all been here.

-------------

(Incidentally, when I went to the Outlook office with DVDs for their photographer to shoot one of the rookies thought I was a Palika shop-owner. “Aap yeh DVDs kitne ki bechte hain?” he asked. Clearly the stubble and the upward curl had worked well.)

Sunday, January 15, 2006

The results are in...

Thanks to everyone who voted for Jabberwock, and congratulations to the other winners. Most of all, thanks to Debashish for devoting so much of his time to putting the Indibloggies together, clarifying the rules, organising repolls, compiling results, writing long posts etc etc. I would never have had the patience myself to do something like this, so appreciate it.

Back to regular posting now.

Friday, January 13, 2006

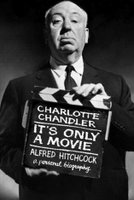

It’s Only a Movie: cosying up to the Master

Normally I consider book-jacket blurbs to be of worth only for their comic value, but this one caught my attention immediately. “The best book ever written about my father!” exults Patricia Hitchcock on the cover of Charlotte Chandler’s It’s Only a Movie, subtitled Alfred Hitchcock: A Personal Biography.

Normally I consider book-jacket blurbs to be of worth only for their comic value, but this one caught my attention immediately. “The best book ever written about my father!” exults Patricia Hitchcock on the cover of Charlotte Chandler’s It’s Only a Movie, subtitled Alfred Hitchcock: A Personal Biography.I’ve read more books on Hitchcock and his films than on any other single subject. I used to be obsessed with the man’s work (by “used to be” I don’t mean I hold him in less regard today, just that I reached a saturation point and moved on to other things). His films spoke to me more directly than those made by other directors who were more acclaimed for the depth and seriousness of their work (but who, ironically, took the easy way out by keeping their themes and ideas on open display – unlike Hitch, who kept his buried within the narrative structures of his films). Hitchcock’s movies gave me a more immediate understanding of the countless little ways in which we deceive and manipulate each other, and ourselves. They also taught me that a work of art doesn’t have to contain meaning at only the most obvious, superficial level for it to be profound.

Like I said, there was a point where I could no longer bear to look at another book on Hitchcock; my instinctive response to a new biography was “ho-hum, what’s left to be said”. But Chandler’s book is very entertaining, insightful and notably different from most other indepth studies. Firstly, she doesn’t discuss Hitchcock’s films at great length, or try to bring a critical perspective to them (it’s clear that she doesn’t think of herself as a film critic, or maybe she just feels that enough dissertations have already been written on these movies). Instead she follows a set format, moving chronologically from one film to the next, providing a short synopsis and – this is the meat of her book – recording quotes and observations from cast and crew members involved with each film (including Hitchcock himself on occasion). No attempt is made at linking chapters thematically.

This makes It’s Only a Movie sound tedious and lazily strung together, but that isn’t the case at all. Chandler’s approach may seem unstructured and messy at first but gradually, as the quotes add up and we move through a career that spanned over 50 years from the silent era to the late 1970s, a portrait of the man begins to emerge. Importantly, it isn’t a definitive portrait but a kaleidoscopic one, for Hitchcock was many things to many people and by speaking to so many respondents Chandler has brought out different sides of his personality.

Most actors, for instance, had ambivalent (if not downright unpleasant) memories of working with Hitchcock - not surprising given his famous dismissal of performers as “cattle”, or chess pieces to be moved around. His great visual sense meant he had the entire film ready in his mind before a single scene had been shot (he prided himself on never having to look into the camera) – but this could naturally be frustrating for actors who might want to improvise a little while shooting. “People say Hitch wasn’t spontaneous,” James Stewart once said, “but he was. It’s just that all of his spontaneity occurred on paper before he got to the set!” Tippi Hedren, who starred in The Birds and Marnie, still has bad memories. “He was more careful about how the birds were treated than about me,” she said. “I was just there to be pecked.”

But a few performers (not just his favourite blondes) also remember him as uncommonly generous and non-intrusive. “He wasn’t a backseat actor,” recalls Hume Cronym. “He expected us to know our jobs. I don’t consider that being unconcerned with your actors.” And during the intense scene between Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) and Detective Arbogast (Martin Balsam) in Psycho, the two Method actors were able to persuade the orthodox director to ditch his original storyboard to allow a scene that would permit overlapping dialogue.

Some things about Hitchcock are beyond dispute though – his talent for macabre practical jokes (like stepping into a crowded elevator with a friend and loudly saying “I hope you got all the blood off the knife” just as they had reached their floor and were about to get off). Or the wordgames that would confuse his crew when he gave them instructions: “Dog’s feet” was his code for “pause” (“Dog’s feet” = “paws”) and “don’t come a pig’s tail” translated meant “don’t come twirly” = “don’t come too early”.

Then there were his ribald little jokes, all the more effective for being delivered in a deadpan tone, and because they were so at odds with his very Brit properness. “There’s hills in them thar gold!” he whispered to Grace Kelly once; she was wearing a low-cut gold gown. “I found it especially amusing,” she recalled, “because Hitch was always so decorous and dignified with me.” He also had a habit of saying, “Call me Hitch, without a cock” to people when he wanted them to be informal with him. This last bit is almost a refrain in Chandler’s book, so much so that after a while it stops being silly and becomes endearing.

The most notable thing about this book is the sheer number of people Chandler has spoken to. A professional biographist (she’s written books on Billy Wilder, Groucho Marx and Federico Fellini before this), her style of working is remarkable – it appears that she either has a photographic memory or takes notes assiduously every time she happens to meet someone who might have a useful anecdote to relate. She did of course interview many respondents especially for this project, but many quotes are drawn from meetings with people from several decades earlier; this book is full of sentences like “A few years ago Gregory Peck told me that when he was working with Hitch…” or “I met Sir Michael Redgrave at his last birthday party and he mentioned that…”, all served up in the most offhand way. (How does this woman know so many people, I kept wondering. I couldn’t find much about her on the Internet.) But some of the most rewarding interviews are with the bit-players: with Georgine Darcy, for instance, who played the tiny role of the bouncy “Miss Torso”, one of the many people James Stewart looks at through his binoculars in Rear Window.

I can’t quite agree with the Patricia Hitchcock blurb, but this is certainly the cosiest and most personal Hitchcock book I’ve yet read. Which is just the kind of relief we need now from the surfeit of tomes that over-analyse and dissect his movies (though I love those too!). As Hitch would often say when people started taking things too seriously, “It’s only a moo-vie.” It’s another matter that he never believed it himself.

(Another post coming up soon, about other books on Hitchcock.)

Tuesday, January 10, 2006

Kiran Nagarkar at IHC

The man really is a delightful speaker – very natural, very funny in an unforced way, and he uses “man” to end a sentence more endearingly than any non-Jamaican I know. So I didn’t get too impatient about the fact that he was also Ostentatiously Self-Deprecating, never missing a chance to take little digs at himself. That kind of thing usually gets ho-hummish after some time.

The theme of the Katha festival is “City Stories” and so Nagarkar started by talking about how it’s infra dig to speak Marathi in Mumbai (unless you’re a hardcore Maharashtrian), and how people no longer name their girls Ganga because “Ram” and “Ganga” had become commonly associated with servants in Parsi households. But soon he manouevred his way to the topics he really wanted to discuss: how tragic it is that languages around the world are being allowed to die out, and the case for teaching everyone four languages at school level. “We need more bilingual writers,” he said, mentioning the late Arun Kolatkar. “Each new language we learn opens up hitherto dead pathways in our brain and helps expand the ways in which we think. And it isn’t at all difficult to learn a number of languages if you start early in life.”

“More than anything else, the role of a writer is to ensure that we do away with the Other in the world. Looking at Pakistanis, or Iraqis, or whoever, as the Other is simply a means of dehumanising and then demonising them. It makes it easy for us to disregard that they have the same feelings as us.”

And: “Saare jahaan se acha…” is a terrible thing to teach young children. Patriotism is one of the worst qualities – unless you expand it to encompass the world.” (Hear, hear!)

For obvious reasons I also enjoyed Nagarkar’s little anecdote about being interviewed by a journalist who was uninterested in anything he had to say about his work but kept asking him why he had shifted to writing in English from writing in Marathi. “At some point I asked him if he had read my latest book and he looked back at me, astonished, and said ‘no of course not, but I’ve looked it up on the Internet’.” (This would be a good time to re-link to this article Rana Dasgupta wrote for Tehelka a few months ago.)

Leaving, I picked up Seven Sixes are Forty-Three, the translation of Nagarkar’s 1974 Marathi novel Saat Sakkam Trechalis. Look forward to reading it. (If you aren’t familiar with his work, do try to find the time for Cuckold or Ravan & Eddie.)

Tip: If you’re in Delhi and have more free time on your hands than I do, winter is a great time to hang around the IHC. Look through their events schedule for the day, drift in and out of rooms; there’s always something interesting going on in this supposedly cultureless city – film screenings, script-and-direction workshops, books readings, even puppet theatre festivals. (Don’t do what I did last evening though – I loitered about for over 10 minutes at what I thought was a Katha event, before realising it was a dinner party being hosted by the Fourth Annual Plumbers’ Convention.)

Monday, January 09, 2006

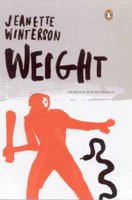

Myth series contd: The Penelopiad, Weight

-- Hercules to Atlas, in Jeanette Winterson’s Weight

And what did I amount to, once the official version gained ground? An edifying legend. A stick used to beat other women with. Why couldn’t they be as considerate, as trustworthy, as all-suffering as I had been? That was the line they took, the singers, the yarn-spinners. Don’t follow my example, I wanted to scream in your ear – yes, yours. But when I try to scream I sound like an owl.

-- Penelope, in Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad

What’s a retelling without a few funny anachronisms, right?

Atwood and Winterson have had a lot of fun with their contributions to Canongate’s myth series, and both books are over-clever in parts. But revisionism done well can be entertaining too. In The Penelopiad, Penelope hears conflicting reports about her husband Odysseus – one says he had been in a fight with a giant one-eyed Cyclops, another says no, it was only a one-eyed tavern-keeper and they were squabbling over the bill. The Atlas-Hercules banter in Weight throws up some inventive slang for phallic activity (Hercules’s “prick goes kangaroo” when he sees the Goddess Hera, whom he simultaneously lusts for and fears). And Penelope's 12 maids, destined to be hanged (and crucial to Atwood’s version of the story), pop up with little ditties in between her narrative; this is The Handmaids’ Tale as performed by Gilbert & Sullivan:

Atwood and Winterson have had a lot of fun with their contributions to Canongate’s myth series, and both books are over-clever in parts. But revisionism done well can be entertaining too. In The Penelopiad, Penelope hears conflicting reports about her husband Odysseus – one says he had been in a fight with a giant one-eyed Cyclops, another says no, it was only a one-eyed tavern-keeper and they were squabbling over the bill. The Atlas-Hercules banter in Weight throws up some inventive slang for phallic activity (Hercules’s “prick goes kangaroo” when he sees the Goddess Hera, whom he simultaneously lusts for and fears). And Penelope's 12 maids, destined to be hanged (and crucial to Atwood’s version of the story), pop up with little ditties in between her narrative; this is The Handmaids’ Tale as performed by Gilbert & Sullivan:We are the maids

The ones you killed

The ones you failed

We danced in air

Our bare feet twitched

It was not fair

Despite a tendency to be show-offish, both authors acquit themselves well enough. Winterson does use the Atlas myth to make some humdrum observations about walking away from the world’s burdens, and “carrying only what you want to keep”. I’d much rather have listened to U2’s “All That You Can Leave Behind”. But her Atlas is a moving creation and there is unexpected poignancy in his encounter with Laika, the Russian dog sent into space in 1957 (no, this isn’t as bizarre as it sounds!).

Despite a tendency to be show-offish, both authors acquit themselves well enough. Winterson does use the Atlas myth to make some humdrum observations about walking away from the world’s burdens, and “carrying only what you want to keep”. I’d much rather have listened to U2’s “All That You Can Leave Behind”. But her Atlas is a moving creation and there is unexpected poignancy in his encounter with Laika, the Russian dog sent into space in 1957 (no, this isn’t as bizarre as it sounds!).Similarly, Atwood’s take on Penelope as a female-goddess cult leader gets a bit distracting towards the end, but the little asides work quite well – for instance, the way she presents Penelope’s envy of Helen in terms of the college Ugly Duckling’s resentment of the most popular girl in class. Or Penelope’s account of life in Hades (which is where she narrates her story from). High comedy is mixed with high drama in a way that does justice to the tone of the original myths.

Coming up in the Myth series: a retelling of the Daedalus and Icarus story by Donna Tartt, as well as works by A S Byatt, David Grossman and Alexander McCall Smith.

Sunday, January 08, 2006

Shameless canvassing

(I like the whole humanities thing. Chandrahas and I were joking the other day that while the rest of the blogosphere organises itself into pro-libertarians and anti-libertarians, we’re the only “humanitarians” left.)

And while I’m at it, here are some favourites in the other categories:

In the ridiculously over-crowded Indiblog of the Year category, my personal favourites are Amit and Arnab, with nods to Uma and Dilip. (Karthik of Etcetera should have been in the Humanities category as well, but I’m relieved he isn’t.)

For Topical IndiBlog, difficult to pick between Sonia Faleiro, Atanu Dey, The Acorn and Youth Curry. For Lifetime Achiever, The Examined Life. For Best Group Blog, SEA-EAT and Sepia Mutiny.

Don’t know enough about the other nominees, but whose idea was it to have a category for “IndiBlog with the Best Tagline” but none for “Personal IndiBlog”? Oh well, I’ll be gracious and avoid ranting – for now.

Vote here.

P.S. All competitive awards are Bad. Never forget this.

Saturday, January 07, 2006

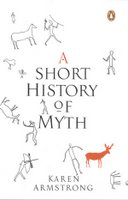

Myth-making in an age of reason

“…human beings fall easily into despair, and from the very beginning we invented stories that enabled us to place our lives in a larger setting…[Mythology] helped people to find their place in the world and their true orientation. We all want to know where we came from, but because our earliest beginnings are lost in the mists of pre-history, we have created myths about our forefathers that are not historical but help to explain current attitudes about ourselves, neighbours and customs. We also want to know where we are going, so we have

devised stories that speak of a posthumous existence…”

Armstrong emphasises that mythology is not an early attempt at history and that myths do not claim to be objective truths. But their purpose has been widely misunderstood in modern times, where the tendency is to scoff as mythology as being unscientific and opposed to the Age of Reason. In the conflict between logos (reason) and mythos, the importance of the latter was undermined – to the extent that defenders of myths were forced into the ludicrous position of evolving “proofs” for the existence of Allah or the “literal truth” of everything stated in the Bible.

A Short History of Myth discusses the development of myths and the change in people’s attitudes towards them through various periods of human existence: the Palaeolithic and Neolithic Ages; the first civilizations when the growth of cities occurred; the Axial Age (c. 800 to 200 BC – called so by the German philosopher Karl Jaspers because this period “was pivotal in the spiritual development of humanity”); the post-Axial period (c. 200 BC to 1500 AD); and the Great Western Transformation (c. 1500 to the present day), a reason-obsessed age when logos and myth became incompatible. “God is dead” announced Nietzsche in 1882. “In a sense he was right,” says Armstrong. “Without myth, cult, ritual and ethical living, the sense of the sacred dies. By making ‘God’ a wholly notional truth, reached by the critical intellect alone, modern men and women had killed it for themselves.”

A Short History of Myth discusses the development of myths and the change in people’s attitudes towards them through various periods of human existence: the Palaeolithic and Neolithic Ages; the first civilizations when the growth of cities occurred; the Axial Age (c. 800 to 200 BC – called so by the German philosopher Karl Jaspers because this period “was pivotal in the spiritual development of humanity”); the post-Axial period (c. 200 BC to 1500 AD); and the Great Western Transformation (c. 1500 to the present day), a reason-obsessed age when logos and myth became incompatible. “God is dead” announced Nietzsche in 1882. “In a sense he was right,” says Armstrong. “Without myth, cult, ritual and ethical living, the sense of the sacred dies. By making ‘God’ a wholly notional truth, reached by the critical intellect alone, modern men and women had killed it for themselves.”But there is hope. Armstrong turns to poets, painters and novelists as the great myth-makers of our time: “It has been writers and artists, rather than religious leaders, who have stepped into the vacuum and attempted to reacquaint us with the mythological wisdom of the past.” She discusses Eliot’s The Waste Land, Picasso’s Guernica, Joyce’s Ulysses, Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. And she ends on an optimistic note:

“A novel, like a myth, teaches us to see the world differently; it shows us how to look into our own hearts and to see the world from a perspective that goes beyond our own self-interest.”In a sense, then, myths continue to be written all around us. And so it’s fitting that for its Myth series, Canongate has called on the services of leading novelists like Margaret Atwood, Jeanette Winterson, A S Byatt and Donna Tartt. The Penelopiad, Atwood’s retelling of The Odyssey from the perspective of Odysseus’s wife Penelope, and Weight, Winterson’s account of the meeting between Atlas and Hercules, are out in paperback now. Posts on those books to follow soon.

P.S. I’m not sure how Armstrong can be so certain about the true intentions of mythmakers and storytellers in the ancient world, or about their attitudes to their Gods, but the idea of mythology being separate from religion (as we know it today) is an appealing one. To take a simplistic example, I always think of the Mahabharata as an incredibly rich, complex human drama – an empathetic record of different lives and conflicting motivations – rather than as a story rooted in divinity. Krishna is most interesting not when he is seen an incarnation of Vishnu, fully aware of his celestial purpose, but when he is an ordinary man trying to balance the larger picture with his own human concerns (the respect and affection he feels for some of the people fighting on the Kaurava side). In this case, the supernatural element of the story (the association of Krishna with a remote God) can be seen as a metaphor for human beings trying to overcome their baser sides and reaching for godliness.

Friday, January 06, 2006

The boy in the bubble

And right at the centre of it all, stonewalling away flamboyantly, is this incredibly versatile, naturally talented player who time and time again errs on the side of caution – refusing to take initiative when initiative is required – while still averaging nearly 70 in the past five years. Kallis is one of the reasons for the strong dislike of the South African team that I developed a few years ago. I’ve actually had nightmares about being strapped to a chair, eyes prised open (Alex-in-A Clockwork Orange-style), and being forced to watch a second-wicket partnership between him and Gary Kirsten; 180 runs in 100 overs or thereabouts.

Today Graeme Smith did just about the boldest thing I’ve ever seen a South African cricketer do against Australia, by declaring early and giving them nearly 70 overs to chase 287. But if (as English points out in his article) Kallis had shown a little more initiative while compiling his first-innings century, his team might have had more time to square the series.

Thursday, January 05, 2006

Pak-pining

Coincidentally all these gentlemen blog, in varying degrees. There’s the noble Headlines Today journalist Shamya Dasgupta, an old friend from the pre-journalism days (that’s long before anyone had cellphones, if you want an easier reference point). There’s Amit, with whom much fun has been had in the last few days, and who regaled us with cricketing cliches the last time he covered a series. And now I learn that young Chandrahas will be touring as well.

The closest I’ve ever come to covering a cricket match is when I watched a Test on TV and then mailed "match reports" to thenewspapertoday.com (where I was working the graveyard shift at the time; so basically double duty). And even that was India-Zimbabwe. Oh well. Have fun guys, and spare a thought for me when you’re feasting on kebabs. (Not the galoutis though, you’re welcome to those.)

Amity sued

I did a bit of legwork for the story (some of my inputs here) but 99 per cent of the work has been done by Rashmi, and congrats to her. Hope the abuse doesn’t reach the levels touched when the IIPM controversy happened.

The full story here (read all five links).

Monday, January 02, 2006

Belated books list 2005

Arthur & George (Julian Barnes)

One of Barnes’s very best works and it’s a shame he missed out on the Booker. A beautiful fictionalisation of an early 20th century case where Sir Arthur Conan Doyle defended a young solicitor accused of animal-slaughter, this is as much an examination of the relationship between blind faith and rational knowledge as it is a study of two very different men.

(Full review here.)

Snow (Orhan Pamuk)

(Not strictly a 2005 book but close enough.) Pamuk’s iconic work is still My Name is Red, and for easily understood reasons – but Snow is my personal favourite. The melancholy poet Ka, caught in a crossfire between secular and fundamentalist Islamists, gets my vote as the most unforgettable fiction character of the year. A great absurdist work, which doesn’t make it any less heartbreaking.

(Related post here.)

Pundits From Pakistan (Rahul Bhattacharya)

Just when I’d made up my mind never to read another cricket book published in India, along came this enlivening account of the 2004 India-Pakistan series, which eschews the tired match-report narrative style and provides a compelling account of what was happening off the field. Bhattacharya’s enthusiasm as a young reporter on the tour of his life shines through on every page.

(Full review here.)

The Argumentative Indian (Amartya Sen)

Whatever you think of Sen’s central thesis that India’s long tradition of constructive debate is responsible for the country’s pluralism, the essays collected here are mind-expanding; here’s an academic who can write forcefully and lucidly, without resorting to the kind of jargon that drives the casual reader away.

(Longer post here.)

The Historian (Elizabeth Kostova)

A dark horse of a book that just continued to grow on me against all expectations – until the silly-ish ending. This is the Dracula myth reworked, with the 15th century ruler Vlad the Impaler in the starring role. Loved the leisurely pace at which the narrative unfolds (and this is coming from someone who usually has little patience with long-winded stories).

(Full review here.)

Who Killed Daniel Pearl? (Bernard Henri-Levy)

Renowned French philosopher/former war correspondent (!) Henri-Levy pulls no punches in this recreation of the kidnapping and brutal assassination of the American journalist in 2002. The conclusion, and the author’s outright condemnation of Pakistan, were too unequivocal for my liking but this gets top marks for his depiction of the inner workings of terrorism, and especially for his portrayal of the monstrous Omar Sheikh.

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Vol II (Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill)

Brilliant sequel continues the adventures of the unlikely group of heroes from late 19th century fiction. Sherlock Holmes shows up in a flashback, but Mr Hyde is the star here.

(Longer post here.)

The Year of Magical Thinking (Joan Didion)

Didion’s “year of magical thinking” was one in which her husband of 40 years, the novelist/screenwriter John Gregory Dunne, suddenly collapsed and died of a coronary, while their daughter came out of an induced coma only to undergo major brain surgery a few months later. This territory – the nature of grief – has been covered before, but rarely with such power and honesty.

Never Let Me Go (Kazuo Ishiguro)

Not my favourite Ishiguro by a long way, but can’t leave him off this list.

(Full review here.)

And if I had to pick one favourite:

We Need to Talk About Kevin (Lionel Shriver)

The most viscerally effective, thought-provoking book I’ve read in the last year, even when it skirts slasher-movie territory. The first 100 pages in particular provide a searing look at the mindgames that go into a couple’s decision to have a child, even when one of them isn’t ready for it. As powerful and illuminating as any of the non-fiction by Richard Dawkins or Steven Pinker, which covers similar territory.

(Full review here.)

And because I'm running out of time, others in the top 20:

The Manticore’s Secret (Samit Basu)

Tigers in Red Weather (Ruth Padel)

Patna Roughcut (Siddharth Chowdhury)

Gilead (Marilynne Robinson)

Friends, Lovers, Chocolate (Alexander McCall Smith)

The Kapoors (Madhu Jain)

Out of My Comfort Zone (Steve Waugh)

Surface (Siddhartha Deb)

On Beauty (Zadie Smith)

(And my 2004 list here.)

Update: just for the record I finished 98 books in 2005, well below my earlier average and also, in tragic Bradman-like fashion, falling short of a crucial century. My favourites among the older books I read for the first time include Philip K Dick's The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, Philip Roth's The Counterlife, Murakami's A Wild Sheep Chase, Ira Levin's The Boys from Brazil and Gaiman's Sandman 4: Season of Mists. Too lazy to link - go look them up yourselves.