Last week I did a short phone interview with the actor Tovino Thomas, for India Today. The Q&A is below. Before that, some thoughts on Tovino, whose work I have been enjoying in recent times – especially last year’s Kala (which he also co-produced) and Kaanekkaane, and the new superhero film Minnal Murali (which was the peg for the India Today interview).

Though Tovino is, to put it mildly, a good-looking man with considerable screen presence, that in itself doesn’t account for the part he is playing in the ongoing Malayalam cinema renaissance. What’s more notable is that much of his best work gets its tension from the contrast between his hunky charm on the one hand, and a vulnerability – or in some cases, unlikability – in his characters.

Some fine films have used this dichotomy to terrific effect: in both Kala and Kaanekkaane, for instance, Tovino’s personality and physical appearance help subvert a narrative, or keep us guessing. In the heavily stylized Kala, the establishing sequences, including an intense lovemaking scene, suggest that his alpha-male character Shaji is the protagonist (even though he looks a little too feral to be a straight “hero”). But as the narrative continues Shaji loses much of his self-assurance and we see him in a very different light. Meanwhile, in Kaanekkaane, as a man whose wife died in an accident, Tovino looks lost and distracted, then shows heartfelt emotion near the end – but much of the film’s suspense hinges on the possibility that the character is a philanderer who lied to his ex-father-in-law; so what else might he be capable of?

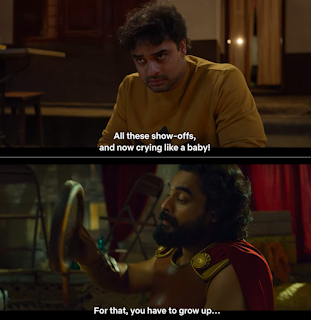

Different sides of the actor’s persona are also on view in Minnal Murali, the acclaimed new superhero film with Tovino as a small-town tailor, Jaison, who discovers new possibilities in himself after a freak lightning strike. The film moves inevitably towards a climax where Tovino gets to strike a heroic pose in his custom-fitted costume, but long before that we see Jaison as a man-child who sulks and mumbles “I deserve a better life!” to himself. In the initial scenes it is the eventual “super-villain” Shibu (wonderfully played by Guru Somasundaram) who seems more soulful and sympathetic, appearing to use his superpowers for a noble cause – saving a little girl – while Jaison is still goofing around. But soon their arcs change. Both men are in some way “unsuitable” – and harassed by people around them, including the police – but as one grows in stature the other regresses.

Different sides of the actor’s persona are also on view in Minnal Murali, the acclaimed new superhero film with Tovino as a small-town tailor, Jaison, who discovers new possibilities in himself after a freak lightning strike. The film moves inevitably towards a climax where Tovino gets to strike a heroic pose in his custom-fitted costume, but long before that we see Jaison as a man-child who sulks and mumbles “I deserve a better life!” to himself. In the initial scenes it is the eventual “super-villain” Shibu (wonderfully played by Guru Somasundaram) who seems more soulful and sympathetic, appearing to use his superpowers for a noble cause – saving a little girl – while Jaison is still goofing around. But soon their arcs change. Both men are in some way “unsuitable” – and harassed by people around them, including the police – but as one grows in stature the other regresses. It's an atypical setting (for the genre), there is slapstick comedy, and the story builds in mundane, unglamorous contexts: Jaison tests his powers by juggling kitchen utensils and stopping a dirty-looking ceiling fan with one hand; clumsily, he discovers that flying is not one of his new gifts. And Tovino – listed the most desirable man from Kerala in a 2018 survey – sends up his own image as a style icon: in one scene, Jaison poses for a camera in an “Abibas” shirt (which he thinks is the real thing) and goes “Stylish, right?” He’s still a long way from being a saviour, and it’s one of the reasons why Minnal Murali is such an unusual and charming superhero movie.

Another thing I liked about the film was that though no time period is specified, it seemed to be set in a pre-liberalisation India that was much more cut off from the rest of the world. (Of course, the small-town Kerala setting already places the film at a remove from the big-city superhero movie; but period-wise it helps that this is a world without the internet or cell-phones.) Speaking as an 80s kid, it was comforting to feel that when Jaison’s little nephew gushes to him about American superheroes, the Superman and Batman being talked about might be the Christopher Reeve and Michael Keaton versions, and that Spiderman is a 5.30 pm cartoon show rather than a feature film. It felt like this dissociated the film from today’s Marvel and DC franchises, which have cluttered the superhero landscape so much that even fans sometimes find it hard to follow the chronologies and interrelationships; or from the ponderous “it’s dark and brooding, so it’s more meaningful than your regular comic-book stories” world of Christopher Nolan’s Batman films.

Here is the Q&A:

As an actor, how satisfying was it to do Minnal Murali? There is a perception that superhero movies aren’t good for “serious” actors, but I felt you got to do a bit of everything in this film.

Yes – I enjoyed playing the many shades of Jaison, from a self-centred, juvenile guy to a superhero who becomes selfless. It’s a gradual transformation, we wanted to keep it subtle, and I had to think like this character: if someone like Jaison gets a superpower, he won’t go out and start saving people the next day, he will just be excited to start with. Evolving into something good over a period of time, looking beyond his own selfish concerns – that’s what provided the character arc and made it worthwhile as an actor.

Did Basil Joseph (the director) and you set out to make it as rooted as possible, to be different from the regular type of superhero movie?

That came naturally to us – Basil and I are both small-town boys who dreamt of cinema as youngsters, then met at some point. I did Godha (2017) with him, we became good friends, our families are close now. It’s a very good working relationship too: he gave me the space to improvise, and I can see it on his face when I give a good performance, which is very encouraging. Also, we both have kids inside us – we don’t want to grow up!

With our budgets, we couldn’t do a Marvel or DC-type film anyway, and you can’t have superheroes flying around skyscrapers in a Kerala setting. We wanted it to be grounded, relatable, we wanted people to believe almost everything in it. So even the reason for the character’s transformation is a natural force, lightning. And we have used practical effects instead of VFX to make it look more realistic. The emphasis was on emotions and character development, which is something that Malayalam cinema has a reputation for.

With a Chitrahaar reference early in the film, the posters shown (Anil Kapoor and the very young Aamir Khan), no mobile phones or internet, I got the impression it was set in the late 1980s. Is that right? If so, it adds to the old-world charm of the story and the sense that it doesn’t belong to a technology-saturated universe.

With a Chitrahaar reference early in the film, the posters shown (Anil Kapoor and the very young Aamir Khan), no mobile phones or internet, I got the impression it was set in the late 1980s. Is that right? If so, it adds to the old-world charm of the story and the sense that it doesn’t belong to a technology-saturated universe.Close enough – we thought of it as being set in 1994 or 95, which was the time of our childhoods, with so many things that we remembered from then. And yes, it would have been a very different type of film if it had computers and mobile phones in it. Technology would have had to play some role in the plot. But we also don’t want to restrict ourselves in future Minnal Murali films. We have passed the first exam, which was the character’s origin story – after this we can do more, take more liberties, change the setting if needed.

Even though this is a grounded superhero film, we are hoping that its success will get regular viewers more interested in Malayalam movies – which is something that a popular-genre film like Minnal Murali can do if it is well made. We in Kerala watch French or Korean movies, so why can’t people watch Malayalam movies? Especially in the OTT era when there is good distribution and promotion for our films. Cinema is a visual language, after all.

Looking at Malayalam cinema from the outside, it seems like there is a lot of genuine collaboration, a spirit of kinship. I have seen you thanked in the credits of films that you weren’t directly involved in the making of (The Great Indian Kitchen, for example). Is the industry more close-knit than the Hindi cinema world?

I think so, yes. There is lots of multi-tasking in our industry – for example, Minnal Murali’s cinematographer Sameer Thahir is also a director and screenwriter. There is healthy competition, based on the idea that the industry as a whole should grow. I have done a cameo recently in Kurup, played a supporting part in a woman-centric film like Uyare, a small part in a Mohan Lal film (Lucifer) – there was no ego involved, and that’s true for most of us. I also like to help out or be involved with films even when I’m not acting in them.

You have been taking uncharted paths as an actor, and now as a producer. Do you choose scripts that will let you experiment or do something different from audience expectations?

I always wanted to be a very good actor and to push my limits – I consider money and fame to be by-products of that process. I’m not saying I’m a great actor, there is scope for improvement, I have taken wrong decisions – but once I understand this then I do my best to correct it. Also, I have to be entertained by what I’m doing – I get bored of myself if I keep doing the same sorts of films or characters. This is also why I try to change my look as much as I can from one role to another, and keep my characters as different as possible. By the way, do watch the trailer of Naaradan, the film I have just done with Aashiq Abu – I have a different appearance there as well, and I’m very enthusiastic about the film.

Even within the Minnal Murali canvas, you look boyish as the young Jaison, but authoritative and like a true hero, a larger-than-life figure, as his father in the flashback scenes.

Yes, that again was something we worked on carefully – that contrast and the sense of character development, the sense that this boy has to grow up to truly understand his father and fill those shoes.

As for producing films: when I come across an amazing script – like Kala, which I had conviction about – I want to push it. But I don’t want to be a full-time producer, I want to concentrate on acting. 2021 was a very good year for me, with three completely different movies and characters (Kala, Kaanekkane, Minnal Murali), and I expect as much from this year.

[Related post: some thoughts on Malayalam cinema as an outsider - a piece I did for Outlook magazine last year]

No comments:

Post a Comment