Jon Favreau’s engaging (if occasionally slow-moving) new film Chef – about a well-regarded restaurant chef who decides to go back to basics after getting a thumbs down from a leading food critic – reminded me of a quote from Alfred Hitchcock’s conversations with Francois Truffaut. In what can be read as a variant on the termite art-elephant art discussion, Hitchcock says of Ingrid Bergman:

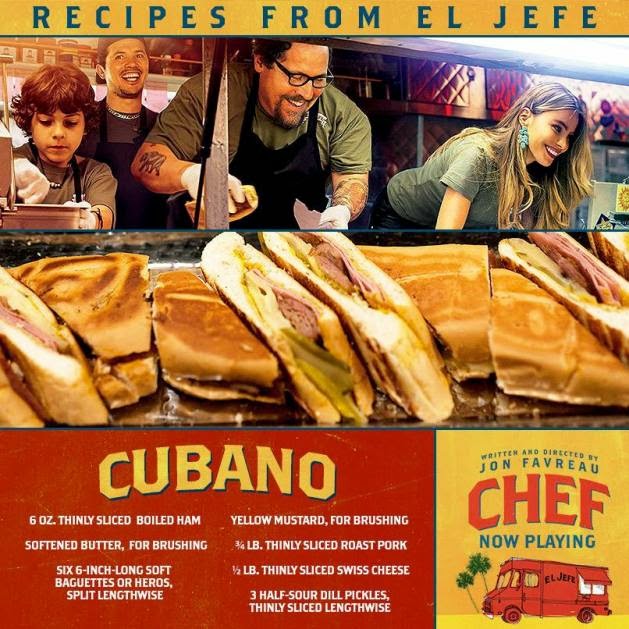

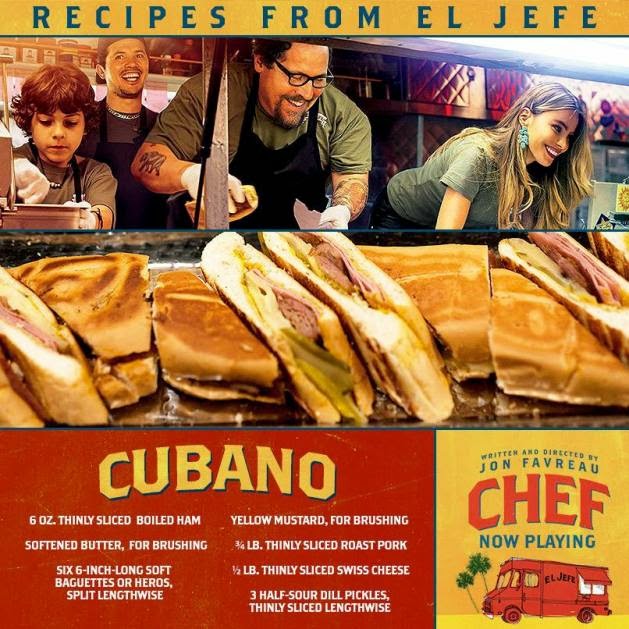

doing something as plebian as manning a food truck, serving Cuban sandwiches and yucca fries (the very definition of a basic lunch) to working-class people. But when backed against the wall, this is exactly what he does. It becomes a journey of self-discovery, as well as a chance to bond with the son whom he never spent much time with earlier, because he was too busy chasing his highbrow creative aspirations.

doing something as plebian as manning a food truck, serving Cuban sandwiches and yucca fries (the very definition of a basic lunch) to working-class people. But when backed against the wall, this is exactly what he does. It becomes a journey of self-discovery, as well as a chance to bond with the son whom he never spent much time with earlier, because he was too busy chasing his highbrow creative aspirations.

And Carl is presented to us as a creative person. He speaks the language of the frustrated, self-questioning artist (“I don’t know if I have anything to say”), he seeks approval obsessively, as in one tragic-comic scene where his friends are sampling one of his preparations and he repeatedly asks “Is it good?” The refrain becomes so pronounced, so desperate, and yet so self-contained that one realises no answer will be good enough for Carl. His friends might honestly think that what he has just served them is the best thing they have ever tasted, they might do everything in their powers to persuade him of this, but once the seed of self-doubt has been planted this man can no longer trust what the people around him say.

Which means there is only one way out for him. He must travel back into the past, into a less self-conscious time when he could enjoy what he was doing without worrying too much about fame or affirmation. (He must learn to become a termite artist again.) So Carl goes to Miami, the place where he got his start in the profession, where his son was born, where he and his ex-wife spent happier times, where he was presumably less stressed, more relaxed. And here he learns (or remembers) that even the lowly Cuban sandwich can, like anything else, be done indifferently or done brilliantly – it can be made with the passion, commitment and attention to detail that can catch the eye of even a highbrow food critic who spends most of his time around haute cuisine. What the “little secretary” in a big film is to Saint Joan in an average film, Carl’s lovingly created street food is to the assembly-line lava cake that brought him so much grief.

relaxed. And here he learns (or remembers) that even the lowly Cuban sandwich can, like anything else, be done indifferently or done brilliantly – it can be made with the passion, commitment and attention to detail that can catch the eye of even a highbrow food critic who spends most of his time around haute cuisine. What the “little secretary” in a big film is to Saint Joan in an average film, Carl’s lovingly created street food is to the assembly-line lava cake that brought him so much grief.

P.S. Chef isn’t “just” about food, or art – it is also about the scarier aspects of the connectedness of modern life; about being a public figure in a world of social media and constant opinion-generation, and how difficult it can be to maintain one’s composure and dignity in such a world. Twitter, selfies, instantly created and uploaded videos…these are all vital ingredients of this film, and the technology-unsavvy Carl bears the brunt of all of them at some point or the other. But the script doesn’t take the easy way out by only bemoaning the negative aspects of these things. They also become an empowering tool for the chef; by the end, they have helped him step out of his ivory tower and reach out to a new “audience”, much like authors forced into self-promotion in the internet age.

P.S. Chef isn’t “just” about food, or art – it is also about the scarier aspects of the connectedness of modern life; about being a public figure in a world of social media and constant opinion-generation, and how difficult it can be to maintain one’s composure and dignity in such a world. Twitter, selfies, instantly created and uploaded videos…these are all vital ingredients of this film, and the technology-unsavvy Carl bears the brunt of all of them at some point or the other. But the script doesn’t take the easy way out by only bemoaning the negative aspects of these things. They also become an empowering tool for the chef; by the end, they have helped him step out of his ivory tower and reach out to a new “audience”, much like authors forced into self-promotion in the internet age.

You see, she only wanted to appear in masterpieces. How on earth can anyone know whether a picture is going to turn out to be a masterpiece or not? When she was pleased with a picture she’d just finished, she would think ‘What can I do after this one?’ Except for Joan of Arc, she could never conceive of anything that was grand enough; that’s very foolish!I’m not saying this is an exact analogy for what happens to Chef Carl Casper in Chef: for one thing, Carl’s troubles begin not because of his own decisions but because his boss Riva orders him to play it safe, to serve the restaurant “classics” when the Eminent Critic comes a-dining. (Is Riva a version of big-studio producers telling Ingrid she is now such a big star that she must only do “prestige projects”?) But we also see that Carl wants to do larger-than-life things. Though he is a likable guy, not the stereotype of an arrogant, snooty achiever, success is an albatross around his neck, and he doesn’t realise that he may have reached the top of a personal plateau. At this point in the film it’s hard to imagine him

The desire to do something big and, when that’s successful, to go on to something else even bigger is like the little boy who’s blowing up a balloon and all of a sudden it goes Boom right in his face […] In those days I used to tell Bergman, ‘Go out and play a secretary. It might turn out to be a big picture about a little secretary.’ But no! She’s got to play the greatest woman in history, Joan of Arc.

doing something as plebian as manning a food truck, serving Cuban sandwiches and yucca fries (the very definition of a basic lunch) to working-class people. But when backed against the wall, this is exactly what he does. It becomes a journey of self-discovery, as well as a chance to bond with the son whom he never spent much time with earlier, because he was too busy chasing his highbrow creative aspirations.

doing something as plebian as manning a food truck, serving Cuban sandwiches and yucca fries (the very definition of a basic lunch) to working-class people. But when backed against the wall, this is exactly what he does. It becomes a journey of self-discovery, as well as a chance to bond with the son whom he never spent much time with earlier, because he was too busy chasing his highbrow creative aspirations.And Carl is presented to us as a creative person. He speaks the language of the frustrated, self-questioning artist (“I don’t know if I have anything to say”), he seeks approval obsessively, as in one tragic-comic scene where his friends are sampling one of his preparations and he repeatedly asks “Is it good?” The refrain becomes so pronounced, so desperate, and yet so self-contained that one realises no answer will be good enough for Carl. His friends might honestly think that what he has just served them is the best thing they have ever tasted, they might do everything in their powers to persuade him of this, but once the seed of self-doubt has been planted this man can no longer trust what the people around him say.

Which means there is only one way out for him. He must travel back into the past, into a less self-conscious time when he could enjoy what he was doing without worrying too much about fame or affirmation. (He must learn to become a termite artist again.) So Carl goes to Miami, the place where he got his start in the profession, where his son was born, where he and his ex-wife spent happier times, where he was presumably less stressed, more

relaxed. And here he learns (or remembers) that even the lowly Cuban sandwich can, like anything else, be done indifferently or done brilliantly – it can be made with the passion, commitment and attention to detail that can catch the eye of even a highbrow food critic who spends most of his time around haute cuisine. What the “little secretary” in a big film is to Saint Joan in an average film, Carl’s lovingly created street food is to the assembly-line lava cake that brought him so much grief.

relaxed. And here he learns (or remembers) that even the lowly Cuban sandwich can, like anything else, be done indifferently or done brilliantly – it can be made with the passion, commitment and attention to detail that can catch the eye of even a highbrow food critic who spends most of his time around haute cuisine. What the “little secretary” in a big film is to Saint Joan in an average film, Carl’s lovingly created street food is to the assembly-line lava cake that brought him so much grief. P.S. Chef isn’t “just” about food, or art – it is also about the scarier aspects of the connectedness of modern life; about being a public figure in a world of social media and constant opinion-generation, and how difficult it can be to maintain one’s composure and dignity in such a world. Twitter, selfies, instantly created and uploaded videos…these are all vital ingredients of this film, and the technology-unsavvy Carl bears the brunt of all of them at some point or the other. But the script doesn’t take the easy way out by only bemoaning the negative aspects of these things. They also become an empowering tool for the chef; by the end, they have helped him step out of his ivory tower and reach out to a new “audience”, much like authors forced into self-promotion in the internet age.

P.S. Chef isn’t “just” about food, or art – it is also about the scarier aspects of the connectedness of modern life; about being a public figure in a world of social media and constant opinion-generation, and how difficult it can be to maintain one’s composure and dignity in such a world. Twitter, selfies, instantly created and uploaded videos…these are all vital ingredients of this film, and the technology-unsavvy Carl bears the brunt of all of them at some point or the other. But the script doesn’t take the easy way out by only bemoaning the negative aspects of these things. They also become an empowering tool for the chef; by the end, they have helped him step out of his ivory tower and reach out to a new “audience”, much like authors forced into self-promotion in the internet age.

i enjoyed 'chef' immensely though i did feel that it was a bit too long and that scar jo's scenes were pretty much pointless. i walked out of the movie desperate to cook at home and try something but also to get my hands on the soundtrack. the movie has a really well curated soundtrack of artists from miami, latin cuban musicians, big band musicians from new orleans and blues by gary clark jr. i think the music added a lot to the sense of rejuvenation during the road movie parts of the film.

ReplyDelete