[Did this piece on a long-forgotten - but now restored - Hrishikesh Mukherjee film for the April 1 issue of Sunday Guardian]

Hindi cinema’s tradition of zombie-love, vampirism and necrophilia has been well-chronicled over the decades, which is understandable, for nearly every major film has splashes of surreal, unexpected horror. The hospital scene near the beginning of Amar Akbar Anthony where Nirupa Roy, in need of a blood transfusion, rips away the tubes and sinks her fangs into the throats of her three sons lying on nearby beds, has been the subject of more Ph.D theses than anyone can count (including a celebrated one titled “Mommie fiercest: the hermeneutics of maternal love and vampirism in popular Hindi film”). Much has similarly been made of the resurrection scene in the climax of Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa where the undead poet Vijay escapes his coffin, strikes a crucifixion pose at the entrance of a hall and sings “Yeh duniya agar mil bhi jaaye toh kya hai?” (“Who cares about the world of the living? It's cosier underground.”)

For decades, heroes and villains have smacked their chomps and droned “Main tera khoon pee jaoonga” at each other, but the word “khoon” has subtler resonances too: our films are full of people betrayed by their blood (hard-hearted relatives) or by their blood cells (prolonged death by cancer). Narcissistic male stars with crumbling faces play characters one-third their age, suggesting a Mephistophelean trade-off. Entire acting careers (Jeetendra? Mala Sinha?) testify that zombies, if they pick their disguises well, can get high-paying jobs. And has any national cinema anywhere in the world – even the Japanese, with their talent for visceral creepiness – offered horrors to rival the sight of Sanjeev Kumar playing nine roles in a single film? No.

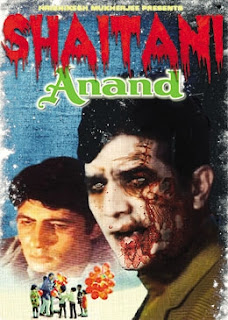

One director steered clear of this ghoulishness for much of his career: in the 1970s, Hrishikesh Mukherjee specialised in gentle, character-oriented scripts and a somewhat narrow definition of “realism” that precluded werewolves and icchadhaari naags. But this is precisely why Mukherjee’s 1980 film Shaitani Anand, lost in the eerie mists of time and recently recovered from film vaults, is such a significant work.

One director steered clear of this ghoulishness for much of his career: in the 1970s, Hrishikesh Mukherjee specialised in gentle, character-oriented scripts and a somewhat narrow definition of “realism” that precluded werewolves and icchadhaari naags. But this is precisely why Mukherjee’s 1980 film Shaitani Anand, lost in the eerie mists of time and recently recovered from film vaults, is such a significant work.

The back-story is as intriguing as the film itself. It began life as a straight sequel to one of the director’s best-loved movies, Anand, but it developed a zombie twist when a young executive producer named Bhootpret Ramsay brought his own ideas to the table. Consequently, the story begins with the beaming cancer patient Anand rising from the grave and setting off to convince his old associates that death, like life, must be lived to the fullest.

This is not typical Mukherjee terrain, but there had been hints of an appetite for morbidity in his earlier work. As the American critic Pauline Kael shrewdly noted, his 1972 film Bawarchi – in which a cook teaches a well-needed lesson to a family intent on devouring each other – anticipated the cannibalistic clan of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre by two years. What exactly was in those innocent-looking pakoras that Raghu the bawarchi was serving the Sharmas?

Raghu and Anand were both played by the same actor, the superstar Rajesh Khanna, whose early filmography – sanguine and twinkling though it appears from a distance – was marked by reflections on life, death and the hereafter. (“Zindagi kaisi hai paheli haaye,” he sang in Anand itself, but there was also “Maut aani hai, aayegi ek din”, crooned in a deceptively upbeat song in Andaz – shortly before the death of his character. And the melancholy number “Zindagi ke safar mein guzar jaate hain joh makaam / Woh phir nahin aate”, which loosely translates as "There's no going back / When you're in zombie land".) By the late 70s Khanna’s career was in free-fall; ironically, his replacement as Bollywood’s most successful star was the lanky Amitabh Bachchan who had played a supporting role in Anand. It is perhaps no surprise then that Shaitani Anand developed into a meta-commentary on the star system. There is profound human tragedy in the story of the sweet-natured Anand becoming a vindictive fiend and stalking his friend Bhaskar – who has changed his hairstyle and no longer recognises him – through Hindi-film studios.

Personally I regret the scrapping of the planned ensemble song that had a number of actors turning into zombies and menacing Bachchan: when an assistant writer jumped ship for the Manmohan Desai camp, a “borrowed” (non-zombie) version of the idea was used in the “John Jani Janardhan” number in Desai’s Naseeb. This omission notwithstanding, Shaitani Anand is a fine horror film as well as a remarkable meditation on stardom as a monster that can suck the life-blood out of you until your wax statue in Madame Tussauds looks more alive than you do. In this sense it’s a movie years ahead of its time (as anyone who has watched Shah Rukh Khan in Ra.One will know) and it’s easy to see why vigorous efforts were made to keep it out of sight. Watch it now!

Postscript: The American film Shadow of the Vampire tells a fictionalised account of the making of the horror classic Nosferatu, built on the idea that the enigmatic leading man Max Schreck was a real-life vampire who feasted on the cast and crew during the shooting. One doesn’t wish to cast similar aspersions on a star of Rajesh Khanna’s magnitude, but it may be noted that the credits list of Shaitani Anand includes several names who never again worked on a Hindi movie. One can only politely wonder about their fate. But perhaps they were Mukherjee and Ramsay’s acquaintances who agreed to help out on a low-budget project and went back to their day jobs afterwards. Yes, that must be it.

For decades, heroes and villains have smacked their chomps and droned “Main tera khoon pee jaoonga” at each other, but the word “khoon” has subtler resonances too: our films are full of people betrayed by their blood (hard-hearted relatives) or by their blood cells (prolonged death by cancer). Narcissistic male stars with crumbling faces play characters one-third their age, suggesting a Mephistophelean trade-off. Entire acting careers (Jeetendra? Mala Sinha?) testify that zombies, if they pick their disguises well, can get high-paying jobs. And has any national cinema anywhere in the world – even the Japanese, with their talent for visceral creepiness – offered horrors to rival the sight of Sanjeev Kumar playing nine roles in a single film? No.

One director steered clear of this ghoulishness for much of his career: in the 1970s, Hrishikesh Mukherjee specialised in gentle, character-oriented scripts and a somewhat narrow definition of “realism” that precluded werewolves and icchadhaari naags. But this is precisely why Mukherjee’s 1980 film Shaitani Anand, lost in the eerie mists of time and recently recovered from film vaults, is such a significant work.

One director steered clear of this ghoulishness for much of his career: in the 1970s, Hrishikesh Mukherjee specialised in gentle, character-oriented scripts and a somewhat narrow definition of “realism” that precluded werewolves and icchadhaari naags. But this is precisely why Mukherjee’s 1980 film Shaitani Anand, lost in the eerie mists of time and recently recovered from film vaults, is such a significant work.The back-story is as intriguing as the film itself. It began life as a straight sequel to one of the director’s best-loved movies, Anand, but it developed a zombie twist when a young executive producer named Bhootpret Ramsay brought his own ideas to the table. Consequently, the story begins with the beaming cancer patient Anand rising from the grave and setting off to convince his old associates that death, like life, must be lived to the fullest.

This is not typical Mukherjee terrain, but there had been hints of an appetite for morbidity in his earlier work. As the American critic Pauline Kael shrewdly noted, his 1972 film Bawarchi – in which a cook teaches a well-needed lesson to a family intent on devouring each other – anticipated the cannibalistic clan of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre by two years. What exactly was in those innocent-looking pakoras that Raghu the bawarchi was serving the Sharmas?

Raghu and Anand were both played by the same actor, the superstar Rajesh Khanna, whose early filmography – sanguine and twinkling though it appears from a distance – was marked by reflections on life, death and the hereafter. (“Zindagi kaisi hai paheli haaye,” he sang in Anand itself, but there was also “Maut aani hai, aayegi ek din”, crooned in a deceptively upbeat song in Andaz – shortly before the death of his character. And the melancholy number “Zindagi ke safar mein guzar jaate hain joh makaam / Woh phir nahin aate”, which loosely translates as "There's no going back / When you're in zombie land".) By the late 70s Khanna’s career was in free-fall; ironically, his replacement as Bollywood’s most successful star was the lanky Amitabh Bachchan who had played a supporting role in Anand. It is perhaps no surprise then that Shaitani Anand developed into a meta-commentary on the star system. There is profound human tragedy in the story of the sweet-natured Anand becoming a vindictive fiend and stalking his friend Bhaskar – who has changed his hairstyle and no longer recognises him – through Hindi-film studios.

Personally I regret the scrapping of the planned ensemble song that had a number of actors turning into zombies and menacing Bachchan: when an assistant writer jumped ship for the Manmohan Desai camp, a “borrowed” (non-zombie) version of the idea was used in the “John Jani Janardhan” number in Desai’s Naseeb. This omission notwithstanding, Shaitani Anand is a fine horror film as well as a remarkable meditation on stardom as a monster that can suck the life-blood out of you until your wax statue in Madame Tussauds looks more alive than you do. In this sense it’s a movie years ahead of its time (as anyone who has watched Shah Rukh Khan in Ra.One will know) and it’s easy to see why vigorous efforts were made to keep it out of sight. Watch it now!

Postscript: The American film Shadow of the Vampire tells a fictionalised account of the making of the horror classic Nosferatu, built on the idea that the enigmatic leading man Max Schreck was a real-life vampire who feasted on the cast and crew during the shooting. One doesn’t wish to cast similar aspersions on a star of Rajesh Khanna’s magnitude, but it may be noted that the credits list of Shaitani Anand includes several names who never again worked on a Hindi movie. One can only politely wonder about their fate. But perhaps they were Mukherjee and Ramsay’s acquaintances who agreed to help out on a low-budget project and went back to their day jobs afterwards. Yes, that must be it.

All I can say is "Wow". I *really* want to see this. What a marvelous premise. If I had done this movie, it would open with Babumoshai lying on the bed, listening to "that" tape. Then he suddenly realizes there is no power. The "tape" has stopped. But Anand is still speaking. He looks around. There is no one there.

ReplyDeleteHa ha ha ha ha!

ReplyDeleteScript completed Jai. I have to see this and it needs to made. You should not have made this an April Fools Joke but just emailed me. Now Vikram Bhatt will make this movie and get Paoli Dam to play a pivotal role.

ReplyDeleteYour filmi knowledge is exhaustive! I am reblogging it on my blog.

ReplyDeleteJai,I have been informed by Ramsay Private Ent Ltd,the premier horrror film archivists in the country,that a special edition DVD of Shaitani Anand will be issued,including special extras like this article and your interview of Rajesh Khanna in his undead disguise+Bhootpret Ramsay's memories of production.

ReplyDeleteP.S. I'm dying to see this movie.Literally.

Illustration by Dev Kabir Malik Design is indeed a masterpiece...the work he has done on Rajesh Khanna is really something...the artwork does bring Rajesh Khanna on par with the other gentleman on the picture...Great work!!!! :)

ReplyDeleteOhh , I was waiting to get back home to read this in peace because of your obvious "zombie prem". But I must say (very truthfully) that this wasn't quite what I was expecting . But then

ReplyDelete"One doesn’t wish to cast similar aspersions on a star of Rajesh Khanna’s magnitude, but it may be noted that the credits list of Shaitani Anand includes several names who never again worked on a Hindi movie. "

, happened and I am happy as a clam :D .

BTW , when are you sending all us readers, "gifts" and "flowers"?

Some real vampires have been commenting on this post. Bloodsuckers.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete