Some went into solitude with the book, but at the threshold of a serious breakdown they were able to open up to the world and shake off their affliction. There were also those who had crises and tantrums upon reading the book, accusing their friends and lovers of being oblivious to the world in the book, of not knowing or desiring the book, and thereby criticising them mercilessly for not being anything like the persons in the book’s universe.Can’t recall the last time I was so frustrated by a book as I was by Orhan Pamuk’s The New Life. Maybe with Ishiguro’s The Unconsoled, which I blogged about here, but The Unconsoled was a book I grew to love – despite the initial bafflement and spots of intense irritation, I was drawn into its strange, surrealistic world. The New Life is another matter. It’s not easy to take to your heart, the way Pamuk’s Snow or My Name is Red are. It’s easier to admire than to like, and I was startled to learn that it was the fastest selling title in Turkish history when it was first published as Yeni Hayat in 1994. But even days after you’ve turned the last page, it’s difficult to stop thinking about it.

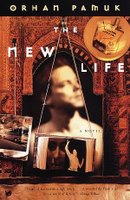

The New Life begins with the sentence “I read a book one day and my whole life was changed”. Through the often-abstruse narrative that follows, this line remains in a sense the closest summing up of what Pamuk’s book is about. The narrator is a young man, Osman (though we learn his name much later in the story), who first sees The Book in the hands of an attractive girl in college and buys it from a roadside stall on the way home. We don’t learn anything specific about the book at this stage, but we understand that Osman has become so affected by it that he comes to believe it has been created for him alone (which is, of course, exactly how many of us feel about things that matter a great deal to us). It seems to show him the path to a new world, the possibility of a new life; he gets obsessed with finding that life, even if it means discarding his present and turning his back on home and family.

The New Life begins with the sentence “I read a book one day and my whole life was changed”. Through the often-abstruse narrative that follows, this line remains in a sense the closest summing up of what Pamuk’s book is about. The narrator is a young man, Osman (though we learn his name much later in the story), who first sees The Book in the hands of an attractive girl in college and buys it from a roadside stall on the way home. We don’t learn anything specific about the book at this stage, but we understand that Osman has become so affected by it that he comes to believe it has been created for him alone (which is, of course, exactly how many of us feel about things that matter a great deal to us). It seems to show him the path to a new world, the possibility of a new life; he gets obsessed with finding that life, even if it means discarding his present and turning his back on home and family.He meets the girl, Janan, as well as her friend Mehmet, who seems to know something about the “new life” described in the book. Soon after this, both of them disappear and the narrator himself leaves home, embarking on a series of dreamlike bus journeys across the country, many of which end in serious accidents (this isn’t commented on much, it’s treated as being an almost inevitable conclusion to a bus journey). He finds Janan again, and following another accident they set off for the town of Guzul to meet a man named Doctor Fine, who is part of “a struggle against the book, against foreign cultures that annihilate us, against the newfangled stuff that comes from the West, an all-out battle against printed matter”.

The New Life certainly touches on the eternal conflict between East and West, a theme that has run through all of Pamuk’s work (it’s poetic justice that the city in which he has lived most of his life straddles both Europe and Asia). But it can also be seen in more general terms, as an allegory about the different ways in which people respond to works of art and how they appropriate certain works for themselves, bringing their own hopes and desires to them – and in the process often setting themselves up for disillusionment. In this context there is great poignancy in the narrator’s ultimate discoveries about the book and how it came to be written, and his uncovering of the mundane truths behind the little signs that have come to mean so much to him.

It’s reasonably obvious (even from the premise) that The New Life is an example of metafiction – self-referential literature that is constantly drawing attention to itself rather than allowing the reader to sink into its world. This sort of thing occurs quite frequently in Pamuk’s books – in the multiple first-person narratives of My Name is Red, for instance (especially the chapters narrated by the “tree”, the “gold coin” and the “horse”), or that superb passage in the theatre-hall in Snow, where the curtain dividing artifice from real life is almost literally torn down.

Take this bit in The New Life, where the narrator learns about a young man’s meeting with an author named Rifki Ray:

Rifki Ray had tried closing the subject as soon as he realised the strange young man at his door was interested in the book. A touching interview could possibly have taken place between the youthful fan and the elderly writer, but for Rifki Ray’s wife – that’s Aunt Ratibe, I interjected – who had interfered, as I had done just now, and had pulled her husband inside.Note the disconcerting effect of “that’s Aunt Ratibe, I interjected” in conjunction with “who had interfered, as I had done just now”. By likening his own action (“I interjected”) to something that occurs in the story he is being told, the narrator is drawing attention to his own status as just another character in a novel. In other words, he’s tearing down the fourth wall between himself and the reader.

Another example of Osman self-consciously examining his own actions occurs when he’s watching TV with an elderly lady and wants to broach a delicate topic. On the screen, a thriller has given way to a documentary, and he says:

In the wee hours of the morning, when the moaning, the murmurs in the night and the death throes were replaced by an educational film on the lives of red and black crabs in the Indian Ocean, I approached the topic sideways like the sensible crab on the screen.The above sentence is also an example of Pamuk’s piquant sense of humour, something that seems improbable considering the huzun (the word for the very particular melancholy he describes as being endemic to his city, Istanbul) that influences and permeates his work. Many of his characters are very downbeat, and themes such as unrequited love, irreconcilable differences between people and general hopelessness about the future are common to most of his books. But as I mentioned in this post about Snow, he’s also very funny in a morbid, absurdist way.

Almost in spite of itself, The New Life has many laugh-out-loud bits. I loved the subplot about Doctor Fine hiring five spies to track his son’s movements: the men are given codenames that are watch trademarks – Omega, Zenith and so on – and after some time the narrator simply begins referring to them as “Dr Fine’s watches”. And the high comedy of this passage doesn’t in the least conflict with the fact that the “watches” in question are heartsick, disgruntled men, doing hard work for little reward (they reminded me of the depressed old detective who was hired to trail the poet Ka in Snow). Pamuk knows how to mix his huzun and his humour without undermining either quality.

What a consignment of geriatric shoemakers, i.e., load of old cobblers.

ReplyDeletePretentious twaddle.

Pamuk, not you. You're paid to write this stuff.

Give me Harold Robbins any day.

You're paid to write this stuff

ReplyDeleteUh, actually no. This was written for the blog, no plan yet to use it elsewhere. So guess I'm a (not-so-old) cobbler too :)

It is frustrating!I really didnt know what to think of it. The title is from Dantes "La Vita Nuova". Pamuk is a cheeky fellow, I love the way he openly lists all his influences. have you read The Black Book? Its similar to The New Life in that after a while the story is beside the point. The Black Book is more nicer but.

ReplyDeleteInteresting. Sounds like a must-read, at least to satisfy my curiosity as to whether I would like it or not :)

ReplyDeleteThe Black Book is much nicer, but.

ReplyDeleteNot more nicer...gah!

Szerelem: yes, The Black Book certainly is a more entertaining read, and faster paced (despite being much longer). Just saw your post on it btw - nice.

ReplyDeleteDon't know how I missed your earlier post on Ishiguro and The Unconsoled. It's the only one of his books I wasn't able to finish -- in fact gave up into the third chapter or so. With When We were Orphans it was the other way round -- I read breathlessly till I was close to finishing it and then wanted to fling it away in a fit of irritation. But stuck on and in the end all was well. Almost.

ReplyDeleteYou make me think it might be worth it to give Unconsoled another try.

Exactly the thoughts I had when I read the book a couple of years ago. A weird experience that you just can't stop thinking about, though you can't particularly say you like the style. I had blamed bad translation for the feeling, and I must say it took me a while to actually get myself to buy another one of his books (this was the first I'd read). The funny thing is, I'm still thinking about it...

ReplyDeleteDM Thomas had a pretty good review of it in the NY Times.

ReplyDeletestrange coincidence i picked up this book the day before the noble was announced. and quite frankly couldnt make head or tale(sic) out of it. maybe i just dont have enuff intelligence or taste to appreciate it...

ReplyDeletebut your review helps make sense out of it. atleast partly... maybe u need book reviews for that too... to explain esoteric/ inaccessible books in 500 words or less...

oh forgot to add this... when i read on the blurb that its the fastest(or was it largest) selling turkish book of all time(or some such)... the phrase "mad turk" suddenly seemed so apt

ReplyDelete;)

warning: politically incorrect comment

I don't think you got the meaning at all.But there is one: let me give you just a hint: write the word book down and creat a samantic map around it...

ReplyDeleteHope you find yourself some new ideas...

Best wishes from Portugal. If you've never heard of Portugal, don't say it doesn't exist. Just look for it in a map, ok?

:)))

I found this book in an old bookshop in Peshawar, Pakistan. I must confess it is a difficult work, but it has its moments where I didn't feel like putting it down for a much needed sip of tea, particularly Usman's introduction with doctor Fine and later his call on aunt Ratibe where together they watch TV. Also splendid review Mr. Jabberwock. I am soon getting down to reading 'Never let me go' by Kazuo and would later check if you have reviewed that as well or not.

ReplyDeletethat's a good story of pamuk, the narrator tells us about the human obsession of love, when people cannot reach what they want, then they feel like frustration, it means that, may i take some psychoanalysis theory, there is meaning of death of narrator where osman fear of abandonment when osman miss janan again

ReplyDeletethat's a good story of pamuk, the narrator tells us about the human obsession of love, when people cannot reach what they want, then they feel like frustration, it means that, may i take some psychoanalysis theory, there is meaning of death of narrator where osman fear of abandonment when osman miss janan again

ReplyDeletethe life is presented here is mind-boggling, just we too have to be in changing regarding of our work style......

ReplyDeleteThanks for your review. I just finished The New Life and loved it. Initially too slow and elusive (= I had no idea what was going on!), I then became immersed in Pamuk's prose. He was a way of writing intricate sentences that are so exact they stop you in your tracks, and there was something thought-provoking on every page. I appreciate the layers of meaning, recurring motifs and the way he cherishes everyday objects. As you point out he touches on themes that mark his later work (east-west, obsessive love, art-life) perhaps more explicitly or questioningly, so it may not work as well as a straight novel - and I love a good old-fashioned straightforward novel - but I loved it so much for the language, rich details and the imperfect characters seeking the angel of life ... or death.

ReplyDeleteA beguiling mystery tale of family and romance. Pamuk is one of the great storytellers of our time.

ReplyDeleteکتاب زنی با موهای قرمز

We're off to see the angel!! Franz Kafka revisits Frank L Baum's Wizard of Oz.

ReplyDeleteTheme of Europeanization does lay heavy and discusses nature of the Angel in Islamic as opposed to Christian tradition. Osman fails to see his life as the journey, subsumed as he is in a target, to me the novel is in part about the nature of desire and when that becomes obsession - Pol, Scotland (just read it in Side, Turkiye)