(wrote this for my Economic Times column)

-------------------------------

Filmed theatre – the recording and subsequent screening of a live stage production – isn’t to many tastes: it usually has neither the immediacy of a good play nor the kinetic visual appeal of a good film. I have been wary of the form ever since my school showed us an astonishingly dull “film” of The Merchant of Venice, which felt like it was created by having a stationary camera placed in the first row at a theatre.  And yet, I greatly enjoyed a recent screening – at Delhi’s India Habitat Centre – of The Motive and the Cue, Jack Thorne’s play about the inter-generational clashes between two major British actors – Sir John Gielgud and Richard Burton, during a 1964 Hamlet production in which the former directed the latter.

And yet, I greatly enjoyed a recent screening – at Delhi’s India Habitat Centre – of The Motive and the Cue, Jack Thorne’s play about the inter-generational clashes between two major British actors – Sir John Gielgud and Richard Burton, during a 1964 Hamlet production in which the former directed the latter.

One reason for this is that I’m a Hamlet-nut and have some interest in the real-life people portrayed here – especially Gielgud, marvellously played by Mark Gatiss (but also Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, who were newly married at the time, and who are mostly shown here in an apartment with pink-ish art design to emphasise their plastic, Hollywood-celebrity life). To fully appreciate this play, you probably need that interest. But even otherwise, The Motive and the Cue didn’t feel static to me. Cinematically you’d never mistake this for an Oppenheimer, of course, but it was thoughtfully put together: some of the establishing scenes were long-shots where you could see not just the entire stage but also part of the original theatre audience sitting in the dark; once a scene proper got underway and the camera “zoomed in” to the action, there were cuts and close-ups. Altogether, it was a strange, compelling experience – not “cinema” as one thinks of it, and yet a reminder that there have been so many different types of films, including the anti-narrative ones, or the Brechtian ones that call attention to their own construction. (I caught myself thinking of Lars von Trier’s Dogville, with its set design made up of painted, labelled outlines of furniture.)

Many of this play’s scenes are about plumbing Shakespeare’s verse for meaning and insight – an inflection here, a pause there, how one performer’s emphasis can be very different from another’s (and how each actor’s life experience – a relationship with a parent, for instance – might inform their approach to the scenes between Hamlet and his father’s ghost). What Gielgud tells Burton about the difference between the motive (the intellect or spine) and the cue (the passion, which ignites the heart) is a version of what Hamlet tells the players while setting his “mouse-trap” for the king.

Most of all, there are poignant moments here which make a case for the filmed-theatre form, in terms of preserving an important stage performance. The Motive and the Cue felt to me like a lament for all the great theatre of the past that was never recorded, and which we can only imagine now. Gatiss’s Gielgud at one point mentions that his major rival Laurence Olivier only played Hamlet on stage once, but will forever be remembered in the role because of his Oscar-winning film version (whereas Gielgud’s own legendary performances of the 1920s can no longer be revisited and exist only in imagination and anecdote). This play often touches on the insecurities of artists, constantly worrying about posterity (even when the present moment seems full of fame and attention), being unsure about their sell-by date. In one scene, almost certainly a fictionalised one, Gielgud and Elizabeth Taylor are chatting. “Can you imagine doing your best work at age 25?” he says ruefully, an allusion to the reputation he built, very young, as the greatest actor of his generation. “Can you imagine doing it at age 12?” Taylor replies sardonically – a reference to her performance as a child actor in the film National Velvet (during the shooting of which she also says she learnt Method Acting from Mickey Rooney, of all people!). Liz is one of the world’s biggest movie stars at this point, a recent Oscar-winner, and yet she and Burton seem very conscious that something valuable has been lost in terms of their integrity as performers; that after the media circus surrounding their affair during the Cleopatra shoot, they need to be more than just fodder for celebrity gossip. Maybe *they* need to do some Shakespeare together – The Taming of the Shrew?

This play often touches on the insecurities of artists, constantly worrying about posterity (even when the present moment seems full of fame and attention), being unsure about their sell-by date. In one scene, almost certainly a fictionalised one, Gielgud and Elizabeth Taylor are chatting. “Can you imagine doing your best work at age 25?” he says ruefully, an allusion to the reputation he built, very young, as the greatest actor of his generation. “Can you imagine doing it at age 12?” Taylor replies sardonically – a reference to her performance as a child actor in the film National Velvet (during the shooting of which she also says she learnt Method Acting from Mickey Rooney, of all people!). Liz is one of the world’s biggest movie stars at this point, a recent Oscar-winner, and yet she and Burton seem very conscious that something valuable has been lost in terms of their integrity as performers; that after the media circus surrounding their affair during the Cleopatra shoot, they need to be more than just fodder for celebrity gossip. Maybe *they* need to do some Shakespeare together – The Taming of the Shrew? That film, made by Franco Zeffirelli a few years later, holds up well today; but it’s widely agreed that the bulk of the other films that Burton and Taylor did together were misfires. (The Leonard Maltin movie guide once “reviewed” their 1968 movie Boom! with the single word “Thud”.) In that sense, it feels like a cosmic joke that while many mediocre films are around forever (assuming anyone wants to seek them out), most great theatre is forever gone. Who is the really sympathetic figure in that interaction between Gielgud and Taylor, one can wonder: the stage legend depressed that there are few who remember his finest work, or the film-star concerned that the limelight is too harsh and persistent?

That film, made by Franco Zeffirelli a few years later, holds up well today; but it’s widely agreed that the bulk of the other films that Burton and Taylor did together were misfires. (The Leonard Maltin movie guide once “reviewed” their 1968 movie Boom! with the single word “Thud”.) In that sense, it feels like a cosmic joke that while many mediocre films are around forever (assuming anyone wants to seek them out), most great theatre is forever gone. Who is the really sympathetic figure in that interaction between Gielgud and Taylor, one can wonder: the stage legend depressed that there are few who remember his finest work, or the film-star concerned that the limelight is too harsh and persistent?

P.S. along with Gatiss, I thought Johnny Flynn (who plays another “Dickie” in the new Ripley series) was very good as Richard Burton. He doesn’t particularly look or sound like Burton initially, but he grows into the part enough that by the end I fancied I could see Burton’s features in his. P.P.S. I also enjoyed the little reference to the birth of Vanessa Redgrave during a performance where her father Michael was playing Laertes to Olivier’s Hamlet on stage in 1937. I remembered the story from Donald Spoto’s Olivier book.

P.P.S. I also enjoyed the little reference to the birth of Vanessa Redgrave during a performance where her father Michael was playing Laertes to Olivier’s Hamlet on stage in 1937. I remembered the story from Donald Spoto’s Olivier book.

Sunday, May 12, 2024

Motives, cues: on theatre, film, stardom and posterity

Saturday, May 11, 2024

About a new anthology of Indian crime writing (from pulp to self-reflexive, and everything in between)

(wrote this long review for Scroll)

----------------

The two-volume Hachette Book of Indian Detective Fiction – edited by Tarun K Saint – has a problem that is a mostly useful one – a problem of plenty. This is something you might expect from a collection of 36 stories (more than two-thirds of them written especially for these books) that fall under the broad rubric “Detective Fiction”, with the many styles and sub-genres implied by that descriptor. In his Introduction, Saint reminds us of the vastness of crime writing – from its tentative roots to the current day, where it often merges with other genres such as fantasy or historical fiction; from thrill-a-minute mysteries (often condescendingly dismissed as “pulp”) to narratives that have deeper sociological underpinnings, or aim for greater realism in their world-building.  Most of those modes are well-represented here. Volume 1, for instance, begins with cosy, old-style mysteries featuring two of the most popular detectives in Bengali literature, Saradindu Bandyopadhyay’s Byomkesh (“The Rhythm of the Riddles”) and Satyajit Ray’s Feluda (“The Locked Chest”) – this is the sort of writing that is endlessly comforting for classic-mystery fans, even when familiarity takes away some of the suspense. The more contemporary stories that come immediately after these – including a poignant one (“Sepal”) by the Tamil writer Ambai, which is as much about love and possessiveness as about crime – are also in the traditional investigative mode. But by the second half of this book, we have reached edgier, more experimental terrain. Now there are philosophical, self-reflexive pieces by Tanuj Solanki (“The Desire of the Detective”) and Anil Menon (“A Death Considered”), which examine the nuts and bolts of suspense writing, mulling on the nature of the narrative-construction required by the genre – as well as the nature of viewer participation, or our willingness to be deceived.

Most of those modes are well-represented here. Volume 1, for instance, begins with cosy, old-style mysteries featuring two of the most popular detectives in Bengali literature, Saradindu Bandyopadhyay’s Byomkesh (“The Rhythm of the Riddles”) and Satyajit Ray’s Feluda (“The Locked Chest”) – this is the sort of writing that is endlessly comforting for classic-mystery fans, even when familiarity takes away some of the suspense. The more contemporary stories that come immediately after these – including a poignant one (“Sepal”) by the Tamil writer Ambai, which is as much about love and possessiveness as about crime – are also in the traditional investigative mode. But by the second half of this book, we have reached edgier, more experimental terrain. Now there are philosophical, self-reflexive pieces by Tanuj Solanki (“The Desire of the Detective”) and Anil Menon (“A Death Considered”), which examine the nuts and bolts of suspense writing, mulling on the nature of the narrative-construction required by the genre – as well as the nature of viewer participation, or our willingness to be deceived.

“In a detective novel, everything and everyone is unreliable. Everybody lies. Every character is an ‘unreliable narrator’, as we writers say in our lingo. That is also exactly how it is in life.”

As it happens, another of the meta stories here – reflecting on the genre, subverting our ideas about it – comes from a much earlier time, and an old master: Rabindranath Tagore's “Detective” (translated by Shampa Roy) is drolly funny, especially when a police-department detective named Mahimchandra bemoans the lack of enterprise and cunning in Indian criminals, and says it would be much more stimulating to work as a crime-solver in Europe. (It’s another matter, of course, that this detective may not be as alert or self-possessed as he likes to think!)

The setting can be futuristic too, or entirely of the mind – there are a few encounters here with sci-fi and speculative fiction. Navin Weeraratne’s “DeathGPT” and Sumit Bardhan’s “Death of an Actress” both – in different ways but with comparable resolutions – involve the death or disappearance of a performer, a detective’s efforts to connect the dots, and end with the questioning of what we call reality. Kiran Manral’s “Witch Hunting” is also about the unreliability of perceptions, or self-perceptions – and not just because it is about a future-era detective time-traveling back to 1984 Bombay (and being startled to discover that no one is to be seen on the road in this most populous of cities). Another highlight, Kehkashan Khalid’s “Andheri Nagri”, centres on an enigmatic woman who could be a serial killer moving through time and space, but could also be viewed as someone who is simply “fixing the world”.

The funniest of these excursions into fantasy, Saad Z Hossain’s “The Detective of Black Korail”, is a witty tale set in a magical space within Dhaka’s Korail slum, where a sheriff named Mok – now living a ghostly life under the patronage of a “witch”– investigates the gory murder of a chauffeur. Much of the pleasure of reading this piece comes from the matter-of-fact interactions between humans and supernatural creatures – hanging over these interactions are also questions of othering and privilege, though Hossain never underlines this.

Incidentally, it gave me a little kick to see that these stories – experimental, cerebral or both – are placed very close to an unabashedly pulpy tale, Tamilvanan’s 1967 “Tokyo Rose” (translated by Pritham K Chakravarthy and published in the delightful Blaft Anthology of Pulp Fiction a few years ago). Here, Shankarlal, immodestly described as “the king of detectives”, is in Tokyo with his wife Indra when things around them – from soap to a cup of tea – suddenly start turning blue (causing nervous Japanese to wonder if this is the effect of a new atom bomb). Shankarlal solves this incidental mystery fast enough, but then gets drawn into an exciting case involving a kidnapping. This story is, to use a cinematic analogy, like an old Rajinikanth film placed amidst a list of modern, detail-heavy OTT shows, and I was very pleased by its inclusion.

**** Volume 2 begins with Vikram Chandra’s masterful “Kama” – close to novella-length and first published in the 1997 Love and Longing in Bombay – which is almost worth the price of admission by itself. It has the cop protagonist Sartaj Singh (who later got a more expanded fictional life in Chandra’s epic novel Sacred Games and the web series adapted from it) trying to figure out the family dynamics of a middle-aged murder victim who has left behind a wife and a teenage son. But the story is as much about the workings of intimacy in its many forms, about lost love (Sartaj and his estranged wife Megha are on the verge of divorce), about the things that people might do to bring newness into their relationships, and even about how one’s parents – living in a less demonstrative age – may have expressed their affection.

Volume 2 begins with Vikram Chandra’s masterful “Kama” – close to novella-length and first published in the 1997 Love and Longing in Bombay – which is almost worth the price of admission by itself. It has the cop protagonist Sartaj Singh (who later got a more expanded fictional life in Chandra’s epic novel Sacred Games and the web series adapted from it) trying to figure out the family dynamics of a middle-aged murder victim who has left behind a wife and a teenage son. But the story is as much about the workings of intimacy in its many forms, about lost love (Sartaj and his estranged wife Megha are on the verge of divorce), about the things that people might do to bring newness into their relationships, and even about how one’s parents – living in a less demonstrative age – may have expressed their affection.

There are other pieces I enjoyed because they involve not a flurry of legwork and clue-scouting, but laidback conversations where different possibilities are turned over. In Rajarshi Das Bhowmik’s “Detective Kanaicharan and the Missing Ship” (translated from the Bengali by Arunava Sinha), a senior inspector – temporarily off duty and looking for ways to occupy his mind – becomes interested in a century-old case involving a ship that apparently vanished in the Bay of Bengal en route to the Andamans with a political prisoner. With little by way of immediate “action” in a story like this (apart from consulting the archives for such banal things as weather conditions in 1913), it is the talk between Inspector Kanaicharan and his subordinate, the gradual unveiling of historical as well as contemporary information, that holds one’s attention – I was reminded, pleasantly, of other stories involving lengthy conjectures (rather than active sleuthing), such as Josephine Tey’s The Daughter of Time and Agatha Christie’s Murder in Retrospect.

Another such story, Ajay Chowdhury’s “The Woman with the Snake Tattoo”, concerns the murder of a jeweller in his office shortly after a woman comes to meet him for an early appointment – this is a more conventionally structured tale about a fresh crime, but the heart of it occurs in a discussion between the detective and his fiancée as they discuss the case, finally arriving at an answer. Madhulika Liddle’s “A Convenient Corpse” – a new story featuring her popular 17th century detective Muzaffar Jung – is similar in that it involves conversations between sleuth and spouse, suggesting that detective work doesn’t have to be a genius’s solitary pursuit, it can be a social or collaborative undertaking too.

Liddle’s story is one of a few historical mysteries in the second book. Another such – also involving a collaborative endeavour, geared at “solving” a society through an examination of its crime – is Anuradha Kumar’s “Sudden Appearances”, a moving tale that playfully uses real-life figures like Emilie Moreau and Rudyard Kipling in a story that appears to have a supernatural element (an appearance by the supposed ghost of a woman who may have died or been killed recently) but also moves past this playfulness to become a serious examination of a social ill of the period.

One truly singular tale in this set – which seems to move beyond most expectations of this genre – is Avtar Singh’s haunting “A Scandal in Punjab”, the last of the 36 pieces. The crime here – the apparent purloining of a watch owned by a brown sahib named Bik during a 1947 pig hunt – is on the face of it less serious than most of the other crimes in the book; but this is also a metaphysical mystery where the timepiece, and those who either own or admire it, are caught in a fierce dance of class, power, manners and one-upmanship in a country heaving towards independence, with all the terrors and excitement involved in this great shift. In its tangential way, then, this is as striking a 1947 story as many others you might read (including a couple in this book, such as Vaseem Khan’s “Ghosts of Partition”).

The timepiece motif in Singh’s story also reminded me Giti Chandra’s “A Darkling Plain” (in Volume 1), about a policewoman investigating the murder of a young student in a posh Delhi University college: though that plot summary doesn’t do justice to the story, which grows in the telling – moving between two separate voices – until it reveals itself to be a comment on caste identity, and identity more generally, a tale where ID cards and ticking clocks become both red herrings and symbols.

****

In critics’ discussions, one truism that often comes up is that in a good creative work, form and content are inseparable – each illuminates the other, and it’s meaningless to try to discuss the “what” and the “how” as individual things. However, this principle doesn’t always apply to the same degree in popular genres like suspense or science fiction, which are often driven by plot twists or denouements. When it comes to a crime story, even a demanding reader may be willing to put up with a certain degree of shoddiness in prose – or in structuring – if the mystery and its resolution are satisfying.

In anthologies as packed as this one, it often happens that a few stories have a slapdash, deadline-driven quality to them, though the ideas are good ones (many of these contributors being suspense specialists). Anirudh Kala’s “No Thermometer for Insanity” – about a death, initially thought to be suicide, in a mental asylum in Amritsar – is an example of a tale that suddenly seems to be in a hurry to wind up, as if the author wanted to quickly end it before going to dinner. Once the amateur detective, Dr Sandhu, figures out what must have happened, the story rushes to its close, blandly informing us about the fate of this and that character in the style of the closing notes in a “based on a true story” film. Then there is “Lethal Air”, by the late Suchitra Bhattacharya, about the murder of an invalid man in his home, shortly after his estranged wife visits him with divorce papers: the solution here is a genuinely engaging one (at the level of the “how-dunit” rather than the whodunit); and yet the explanation, which takes up only the final two pages in a 26-page story, is very rushed. (It doesn’t help that this section is printed without any para breaks or pauses, just a long chunk of prose of the “this happened, then this happened” variety.)

The fact that the above stories still work is testament to their plotting rather than the prose. At other times, the quality of the writing and the description offer their own satisfactions, even when the mystery isn’t spectacular. Arjun Raj Gaind’s “The Diva’s Last Bow” – about a criminologist maharajah solving the back-stage murder of an opera singer in 1890s London shortly after watching her last performance – worked very nicely for me even though it isn’t a complex mystery; Gaind writes with flair, seeming to both channel and parody the mannered speech of the period and milieu, and the protagonist’s voice as he watches a “vulgar” entertainment is enjoyably waspish.

With Salil Desai’s “Sound Motive” too – a much more contemporary story, and very much of its time – I had guessed what the solution might be just from the opening couple of pages (in conjunction with the cheeky epigraph that reads “Based on events that are likely to come true”). I even found myself in sympathy with the killer before the reveal – but this didn’t hinder my enjoyment of the tale, which is told with humour and a flair for misdirection.

***** In all, this is a great-looking pair of books, a collector’s item for the aesthete, with an appealing cover illustration (by Jose) that runs across both volumes when placed alongside each other, and an endpaper design by Manjula Padmanabhan that should bring special pleasure to cat-lovers. Similar attention could have been paid to some of the inside layouts, though: a big let-down is that the original section breaks in Vikram Chandra’s story are entirely missing, which can create some confusion if you’re a first-time reader. (Having read it a couple of decades ago, I was still confused by the way the text ran on and on – and briefly wondered if the story had been more stream-of-consciousness than I had remembered.) In this case, I had access to the original and could compare, but it did leave me wondering if there were other stories that were similarly treated. The copy-editing is a bit slapdash in places, too – in the sense that there has been no real effort to smoothen the prose, insert missing articles, or remove the little typos in the pieces that were carelessly written or hurriedly submitted to begin with.

In all, this is a great-looking pair of books, a collector’s item for the aesthete, with an appealing cover illustration (by Jose) that runs across both volumes when placed alongside each other, and an endpaper design by Manjula Padmanabhan that should bring special pleasure to cat-lovers. Similar attention could have been paid to some of the inside layouts, though: a big let-down is that the original section breaks in Vikram Chandra’s story are entirely missing, which can create some confusion if you’re a first-time reader. (Having read it a couple of decades ago, I was still confused by the way the text ran on and on – and briefly wondered if the story had been more stream-of-consciousness than I had remembered.) In this case, I had access to the original and could compare, but it did leave me wondering if there were other stories that were similarly treated. The copy-editing is a bit slapdash in places, too – in the sense that there has been no real effort to smoothen the prose, insert missing articles, or remove the little typos in the pieces that were carelessly written or hurriedly submitted to begin with.

While the quality of the stories understandably varies, for me there were only a couple of bona-fide disappointments, among them Mahendra Jakhar’s “The Devil of Delhi”, in which dull, carelessly structured sentences plod along one after the other (a conversation where the line “The devil tried to kill me” is followed by “This devil is dangerous, Phoolan” is fairly representative of the story’s dialogue). A solid, imaginative mystery might have salvaged it; instead we get a banal exposition involving drug dealing, and a staged murder that comes off as laughable in an age of DNA testing.

Then there is Sharatchandra Sarkar’s “Bravo! What a Theft”, first published in a Bengali magazine in 1895, and basically, as Saint mentions in his Introduction, a reworking of the Conan Doyle-Holmes story “The Beryl Coronet”. Little of note is added to the original plot (what might leap out at you are the plot loopholes – such as the fact that a father who has described his son as a wild, feckless good-for-nothing who can’t be trusted around money immediately informs that very son about a priceless ornament in a secret hiding place nearby) and I didn’t get the point of using a story that has been lifted wholesale. It also made me more conscious of the fact that among the translated works included in these books, there is a much too heavy emphasis on Bengali stories.

****

But to return to the initial point about a problem of plenty: speaking for myself, reading these two books for professional reasons – and with an interest in all sorts of crime writing, from old-world to avant-garde – I was glad about the variety on offer, and some of the better stories introduced me to writers whose work I wasn’t conversant with (among them Kehkashan Khalid, Salil Desai, Saad Z Hossain, Meeti Shroff-Shah, Ajay Chowdhury, Sumit Bardhan, Rajarshi Das Bhowmik, Navin Weeraratne and Vaseem Khan). This also makes the anthology representative and multi-faceted. A slight hitch, though, is that for the more casual reader with very defined tastes, who is looking only for a certain type of mystery, it may be hard to sieve through the contents and pick out what works for them.

A bit of open-mindedness can help, of course: such readers – if they are willing to be surprised and stirred – will find much worthy material. Though the books are organised by theme, some of the best stories blithely resist categorisation anyway. One of my favourites, Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay’s “When Goyenda Met Daroga” (translated into English by Debaditya Mukhopadhyay), is as much an absurdist or madcap comedy as anything else. It centres on the despairing efforts of a daroga (cop) to apprehend a dacoit named Jhaluram, so adept at evading capture that he often seems to be more myth than man – as a result of which the story gives us throwaway lines like “Sir, this coconut tree is not a tree, it’s Jhaluram in disguise” and “I have a feeling that this red cow is none other than Jhaluram.”

Eventually, once the daroga teams up with amateur sleuth Baradacharan, the dacoit proves surprisingly easy to contact – and yet, throughout, one senses that the point of the story isn’t so much to arrive at a resolution as to show us “good guys” and “bad guys” in a merry dance, spinning tall tales, trying out disguises, just having some fun with each other. By the time one character tells another about an attempt to steal the Taj Mahal, and to ship a portion of Mount Everest to America, you know the story’s value lies in the journey more than the destination. That’s true of most of the really gripping tales in this collection, whether they deal with flesh-and-blood sleuths in a personal crisis, a Himalayan tantrist trained in the occult arts, or an algorithm-based virtual world where detection means identifying patterns.

-----------------

(Earlier Scroll pieces here)

Monday, May 06, 2024

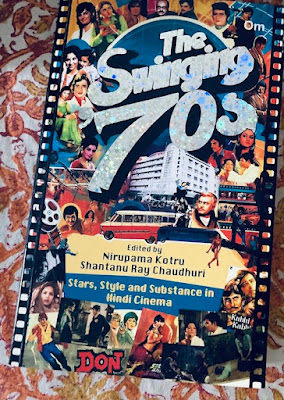

Announcing The Swinging Seventies, a book about 1970s Hindi cinema

A big fat sumptuous book that means a great deal to us film-buffs associated with it (and should come to mean a lot to many readers) is out now: The Swinging Seventies, co-edited by Nirupama Kotru and Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri, is a collection of writings – from personal essays to interviews – centred on the Hindi cinema of that wide-ranging decade.

In February this year Nirupama, Vishal Bharadwaj and I participated in a Jaipur Literature Festival discussion around the book, though it wasn’t yet available. Now it’s here, huge and gleaming, more than 600 pages, and with an impressive roster of contributors. We had a big launch at the India Habitat Centre on May 4, with as many of eleven of the writers present. Nirupama, Uday Bhatia, Gautam Chintamani, Kaveree Bamzai, Aseem Chhabra, Avijit Ghosh and I were on the panel, and many wise words were said (least of all by me – I kept my speech short). Here is a nice write-up about that event by the blogger/reviewer Arushi Barathi (this made me nostalgic about my early years in blogging, 20 years ago, when I used to write quite a bit about the events I attended, even if I wasn’t covering them professionally).

My piece in the book is a personal essay about a particular audio-cassette of my childhood, which also tries to make a broader point about the role that imagination plays in our film-watching, or in our engagement with cinema: what is it like, for instance, to listen to a film before you actually watch it? To construct a film in your own head. But there is plenty more in the book – you can gape at the contents pages and the list of contributors on the Amazon pre-order link, which is here. Please look out for the book, and spread the word to all the movie buffs you know (both those who love 1970s Hindi cinema *and* those who look down on it or are suspicious about its “relevance”).

Vignettes from Jaipur and Delhi below. And here is the link to our short session at JLF in February.