It’s a strange little moment, incongruous to the setting; normally, the man would be using this hushed tone to hard-sell a porn film. More bizarrely, just a couple of days earlier I was speaking with an aunt about the puzzling unavailability of Sathyu’s film in the Indian market. (She saw it a couple of times on its initial release in 1973 and has never been able to get it out of her mind – especially the haunting soundtrack with the “Maula Salim Chishti” qawwali. I saw it as a child on TV and was unable to appreciate it then but was keen to see it again.) For a movie that’s considered one of the key works of the “Indian New Wave” of the early 1970s, it seemed to have gone underground, never to resurface.

It’s a strange little moment, incongruous to the setting; normally, the man would be using this hushed tone to hard-sell a porn film. More bizarrely, just a couple of days earlier I was speaking with an aunt about the puzzling unavailability of Sathyu’s film in the Indian market. (She saw it a couple of times on its initial release in 1973 and has never been able to get it out of her mind – especially the haunting soundtrack with the “Maula Salim Chishti” qawwali. I saw it as a child on TV and was unable to appreciate it then but was keen to see it again.) For a movie that’s considered one of the key works of the “Indian New Wave” of the early 1970s, it seemed to have gone underground, never to resurface.Naturally, I bought the DVD. The print was poor – faded colour, spots and scratches, a couple of seconds of film missing here and there – but not as bad as I'd feared. (I wouldn’t have minded subtitles because the Urdu spoken in the film gets a little dense at times; but again, given these experiences, maybe not.)

Garm Hava's opening montage of images about the Freedom Movement and the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi is followed by a lengthy shot of Salim Mirza (Balraj Sahni) photographed from a waist-high angle at the Agra railway station, waving at a departing train. His sister is leaving for Pakistan and he’s seeing her off; they’ve spent their whole lives in close proximity, now they are being parted in their old age.

This isn’t the last time we'll see Salim waving goodbye to a member of his family. “A hot wind is blowing,” a rickshaw-driver tells him as they leave the station, “Those who don’t get uprooted will get burnt.”

The garm hava in question is the cruel aftermath of Partition, and Salim and his family are being forced to make wholesale adjustments in their way of life. Because of legal complications, their ancestral house is slipping out of their hands. Salim’s daughter Ameena (Geeta Siddharth, in a much more central role than her two-minute appearance in Sholay's family massacre sequence) is separated from the man she is betrothed to. Everywhere, there are subtle changes in equations between Hindus and Muslims. “Sab azaadi ka phaayda apne tareeke se uthaa rahe hain,” (“Everyone is using Independence for their own gain”) sighs Salim when a rickshaw-wallah asks him for two rupees instead of the customary eight annas. A potential landlord assures him that he is unconcerned with a tenant’s religion, but then asks for a year’s payment in advance, because “aap hi ke mazhab ke koi saat maheene ka kiraaya chhod ke chale gaye” (“Someone from your community left without paying seven months’ rent”). Through it all, Salim remains stoical – God will see us through all this, he believes – but his family members, including his son Sikandar (played by the young Farooque Shaikh), aren’t so sure.

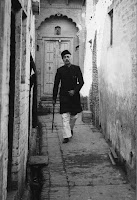

The garm hava in question is the cruel aftermath of Partition, and Salim and his family are being forced to make wholesale adjustments in their way of life. Because of legal complications, their ancestral house is slipping out of their hands. Salim’s daughter Ameena (Geeta Siddharth, in a much more central role than her two-minute appearance in Sholay's family massacre sequence) is separated from the man she is betrothed to. Everywhere, there are subtle changes in equations between Hindus and Muslims. “Sab azaadi ka phaayda apne tareeke se uthaa rahe hain,” (“Everyone is using Independence for their own gain”) sighs Salim when a rickshaw-wallah asks him for two rupees instead of the customary eight annas. A potential landlord assures him that he is unconcerned with a tenant’s religion, but then asks for a year’s payment in advance, because “aap hi ke mazhab ke koi saat maheene ka kiraaya chhod ke chale gaye” (“Someone from your community left without paying seven months’ rent”). Through it all, Salim remains stoical – God will see us through all this, he believes – but his family members, including his son Sikandar (played by the young Farooque Shaikh), aren’t so sure.Some of the acting in Garm Hava is uneven – I thought a couple of the supporting performers were miscast, and the old lady who plays Salim’s mother seems constantly to be looking out for the director’s instructions – but there’s no faulting Balraj Sahni’s immensely dignified performance in the lead role. Sahni invests a great deal in little gestures, speaking volumes with a subtle shift of his eyes, or by cocking his head ever so slightly, or tapping his cane nervously on the floor while speaking to a money-lender. (I don’t want to stretch the comparison too far, but this portrait of a patriarch trying to retain his dignity while the world he once strode proudly through collapses around him reminded me of Burt Lancaster’s wonderful performance as the Prince in Visconti’s Il Gattopardo.)

Equally notable is the film’s anthropomorphising of the Mirzas’ old haveli. The house is given a life and a personality of its own, with the camera freely exploring its interiors, familiarising us with every corner, pointedly framing characters in doors and stairways as if to stress the relationship of these people to their setting; almost suggesting that one is incomplete without the other. We are reminded that ancestral houses become a part of the people who have lived in them for decades (and the haveli can equally be seen as a symbol for the nation), and this is most poignantly realised in the scenes involving Salim’s mother. When the Mirzas have to leave, she resists, clinging to the walls, crying out that she’d rather die than go away. Later, she insists on sleeping on the terrace of their new accommodation, because from here she can see the haveli in the distance. A scene where the dying woman is carried back to the house, in a palki, is shot to suggest her memories of her first trip to the haveli – presumably as a young bride, in a palanquin, decades earlier.

Equally notable is the film’s anthropomorphising of the Mirzas’ old haveli. The house is given a life and a personality of its own, with the camera freely exploring its interiors, familiarising us with every corner, pointedly framing characters in doors and stairways as if to stress the relationship of these people to their setting; almost suggesting that one is incomplete without the other. We are reminded that ancestral houses become a part of the people who have lived in them for decades (and the haveli can equally be seen as a symbol for the nation), and this is most poignantly realised in the scenes involving Salim’s mother. When the Mirzas have to leave, she resists, clinging to the walls, crying out that she’d rather die than go away. Later, she insists on sleeping on the terrace of their new accommodation, because from here she can see the haveli in the distance. A scene where the dying woman is carried back to the house, in a palki, is shot to suggest her memories of her first trip to the haveli – presumably as a young bride, in a palanquin, decades earlier. Most “Partition films” contain moments of strong violence – the movies can’t bring themselves to look away from the horror stories about neighbours killing each other or ghost trains filled with dead bodies, gliding across the fresh borders. And unflinching depictions of this sort can serve a purpose too (although they also carry the danger of trivialisation). But the violence of Garm Hava is subtler: it’s about the uncoiling of the many threads holding together a family, about being uprooted from the only life you knew. This isn’t a flawless film (there’s something a little too convenient, even manipulative, about the way misfortune stalks the Mirzas **) but it’s an important one – a poised, personal, ground-level perspective of a critical time in India’s history – and it’s encouraging to hear that the original print is undergoing restoration. Not a moment too soon, and I hope similar work is done on the under-seen films of other notable Indian directors of that time, Mani Kaul and Kumar Shahani among them.

Most “Partition films” contain moments of strong violence – the movies can’t bring themselves to look away from the horror stories about neighbours killing each other or ghost trains filled with dead bodies, gliding across the fresh borders. And unflinching depictions of this sort can serve a purpose too (although they also carry the danger of trivialisation). But the violence of Garm Hava is subtler: it’s about the uncoiling of the many threads holding together a family, about being uprooted from the only life you knew. This isn’t a flawless film (there’s something a little too convenient, even manipulative, about the way misfortune stalks the Mirzas **) but it’s an important one – a poised, personal, ground-level perspective of a critical time in India’s history – and it’s encouraging to hear that the original print is undergoing restoration. Not a moment too soon, and I hope similar work is done on the under-seen films of other notable Indian directors of that time, Mani Kaul and Kumar Shahani among them.----

** In an essay in his fine book 50 Indian Film Classics, M G Raghavendra points out that the film tries to distance itself from the melodramatic idiom of mainstream Hindi cinema but succeeds only to an extent, and this compromises its overall tone