An old Roman Polanski film I have a lot of affection for is his atmospheric horror-comedy The Fearless Vampire Killers, originally titled Dance of the Vampires. It isn’t usually considered part of the director’s A-list (even now it’s regarded a cult classic at best), but I think it’s a wonderfully well-made film that hits a fine balance between menace and goofy humour – two qualities that don’t normally mix well, assuming anyone even tries to mix them. I enjoy the fact that it defies classification: just when you think you have it pegged as a parody-tribute to the Hammer horror movies, it turns a corner and gives you an image or vignette so beautiful (or frightening) that it transcends nearly anything from the Hammer factory.

An old Roman Polanski film I have a lot of affection for is his atmospheric horror-comedy The Fearless Vampire Killers, originally titled Dance of the Vampires. It isn’t usually considered part of the director’s A-list (even now it’s regarded a cult classic at best), but I think it’s a wonderfully well-made film that hits a fine balance between menace and goofy humour – two qualities that don’t normally mix well, assuming anyone even tries to mix them. I enjoy the fact that it defies classification: just when you think you have it pegged as a parody-tribute to the Hammer horror movies, it turns a corner and gives you an image or vignette so beautiful (or frightening) that it transcends nearly anything from the Hammer factory.

The story involves the many misadventures of old Professor Abronsius and his earnest, wide-eyed assistant Alfred (played by Polanski himself – this is probably his best outing as an actor) as they travel around Transylvania to find and destroy vampires (though I don’t think the word is ever actually spoken – not until the final 20 minutes anyway). They bumble their way around inns, enquire if anyone knows of “a castle in the vicinity”, wonder why each place they go to has large quantities of garlic handing from the ceiling and why the residents appear so nervous. Then an innkeeper’s voluptuous daughter (Polanski’s real-life wife Sharon Tate) is abducted by the creepy Count Von Krolock, and the pursuit begins.

Fearless Vampire Killers holds up quite well today considering it draws heavily on the Hammer template, which now seem so quaint and dated. It’s great to look at – with exquisite shots of the Alpine snows and many graceful scenes, including one of the most balletic vampire attacks you’ll ever see and a tense, funny, nicely choreographed ballroom dance where our heroes try to rescue the heroine from a hall full of aristocratic vampires. There’s even a lovely, tender moment between the Polanski and Tate characters (I think this was the only time they appeared together onscreen) that could easily have come out of any of the great romantic films.

And somehow, when all this is set against the goofier moments (the MGM lion

And somehow, when all this is set against the goofier moments (the MGM lion  turning into a cartoon monster before the opening credits, the manic prancing about of the innkeeper Shagal, the vampires solemnly getting back into their coffins to sleep when dawn breaks), it only adds to the viewer’s disconcertment. You never know when to expect a change of tone: one minute the professor and his assistant could be clowning around like Keystone Kops, the next moment a pair of fangs might be sinking into someone’s throat. It keeps you on the edge.

turning into a cartoon monster before the opening credits, the manic prancing about of the innkeeper Shagal, the vampires solemnly getting back into their coffins to sleep when dawn breaks), it only adds to the viewer’s disconcertment. You never know when to expect a change of tone: one minute the professor and his assistant could be clowning around like Keystone Kops, the next moment a pair of fangs might be sinking into someone’s throat. It keeps you on the edge.

A couple of links (preferably if you’ve already seen the film, or if you’re interested but don’t plan to see it anytime soon). First, this fine appreciation of the musical score: it’s a sequence-by-sequence analysis, so it inevitably gives away everything about the plot. Second, this review, with information on how a severely re-edited version of the film was available in the US for many years – Polanski disowned that version, which no doubt contributed to the film being low-profile for a long time.

P.S. Given that this isn’t considered a “typical” Polanski movie, I was also intrigued by this quote from cinematographer Douglas Slocombe (link via Wikipedia): “I think he (Roman) put more of himself into Dance of the Vampires than into another film. It brought to light the fairy-tale interest that he has…The figure of Alfred is very much like Roman himself – a slight figure, young and a little defenseless – a touch of Kafka. It is very much a personal statement of his own humour. He used to chuckle all the way through.”

(Earlier post on Polanski's Macbeth here.)

My dislike for smiley icons surpasses even my distrust of real-life smiles. Smileys (smilies?) are evil things at most times but what annoys me most is when people use them as a cop-out, to soften the tone of sentences that they fear might otherwise be taken in the wrong spirit. This is so cloying, and so cowardly. It’s like the silly little icon is sniveling on the sender’s behalf: “Look, I might be saying something vaguely sarcastic or provocative here, but I’m really all harmless and Teddy Bear-ish underneath, so please, please don’t take offence! Just love me, okay?”

[For an example of such usage, see the last sentence of this post]

It’s equally bad when a smiley is used as shorthand for dummies – to clarify that a certain remark is, indeed, meant to be funny. This is the equivalent of inserting a laughter track at the end of your own joke just to make things easy for The Undeserving Humourless.

Not that I don’t understand the need for this usage: I’ve complained often enough on this blog that people don’t seem to understand comedy that doesn’t announce itself loudly, that doesn’t come with a large signboard saying “Kindly laugh here.” My repeated exhortations that nothing I say or write is to be taken seriously (except when I proclaim that cats are our last remaining links to the Divine; that’s honest) fall on deaf ears. I write a jokey post about strange and wondrous births in the Mahabharata and the good people at DesiPundit classify it under “Society and Culture” instead of “Humour”. And later someone leaves a comment saying “To take mythology literally to poke fun at Hinduism is a bit sick, don't you think?”

[This means one of two things: 1) I’m so brilliant and subtle that no one currently alive can understand me and my genius will only be recognised 5000 years into the future, when I’m long past caring, or 2) I’m just not as funny as I like to think. Perhaps both.]

But back to the last point about smileys. Despite being grievously misunderstood in these matters, I refuse to use the smiley as a laugh-track. It’s beneath my dignity. Except in very, very rare cases. So a quick note for anyone I’ve ever sent a smiley to, whether on email, SMS or Comments: don’t preen. All it means is that I knew there was just no way you would have got the tone of the sentence otherwise. In short, you’re a pea-brained cretin :-)

Tip for book-lovers based in Delhi, or anywhere in the NCR: drive down to the newly opened Grand Mall in Gurgaon (next to the Bristol hotel) and visit the Landmark store. It’s gorgeousity, especially the graphic novels section – bigger and more comprehensive than anyplace else I’ve seen. Four racks, including all the stuff that’s available elsewhere (the Gaimans, Moores and Frank Millers) but also hordes that isn’t – including several manga titles, many of which I hadn’t heard of.

The other sections are impressive too – saw plenty of books in the Cinema shelf that I haven’t seen in any other Delhi shop. And the display is outstanding. The sheer size of the place (and the stock), with all the shelves neatly categorised and sub-categorised, reminded me of when I first walked, open-mouthed, into London’s Foyles. But the problem – and it’s a big one – is that the pricing seems to follow its own rules. Quite a few of the international publications, especially in the Cinema and Music sections, seemed over-priced. For instance, Faber & Faber’s Lynch on Lynch had two little stickers at the back: one said $12.5 (which works out to roughly Rs 550) but the other sticker (with the shop trademark on it) said Rs 947. (I would’ve picked the book up at the dollar price without giving it a second thought.) The IBH rules didn’t seem to apply.

So no plans yet to turn my back on my favourite stores such as Midland’s, even if they don’t have a comparable variety of titles. But Landmark is certainly worth visiting just to gape at, and to generally feel miserable about. Incidentally the manager told me their second store will be at the soon-to-be-opened mall in Saket and it’ll be much bigger than the first one (60,000 sq ft to the Gurgaon one’s 24,000 sq ft). That's just five minutes from where I stay, so doubtless more miserablism will follow soon.

Here’s an extract from the prologue of Raj Kamal Jha’s third novel Fireproof, to be launched next month: this is part of an opening statement written from beyond the grave by victims of the horrific Gujarat riots of early 2002.

“…during the hours we were killed, the world was a busy place. Girls in bikinis were barred from a Commonwealth summit in Australia to respect “religious and cultural sensibilities”. An institute in Chicago revealed that a 33-year-old American woman had conceived a baby girl “scientifically selected” to ensure she was free of Alzheimer’s.

Closer home, the nation celebrated Pandit Ravi Shankar’s third Grammy and the nomination of a Hindi film [Lagaan] for the 74th Academy Awards…Work continued on the four-lane highways of our Prime Minister’s dream, on sealing the glass atrium of the new mall. The point we are trying to make is this: our killing was certainly not the end of the world. Because elsewhere there was fun, there was frolic, there was the promise of a better future.”

Reading this made me think of a passage from the late William Styron’s celebrated novel Sophie’s Choice. I read that book nearly 15 years ago, but this bit has stayed with me. Background: the narrator, a young man named Stingo living in Brooklyn, has become friends with a Polish Catholic woman named Sophie, a concentration camp survivor. Stingo – and we – learn about the details of Sophie’s experiences in layers, leading up to the climactic revelation that gives the book its title.

Around halfway through the novel, Stingo is reflecting on George Steiner’s thoughts about “the two orders of simultaneous experience” – the phenomenon that even while the worst horrors are being perpetrated on some people, in other parts of the world (or just a short distance away) at exactly the same time others are merrily carrying on with the daily bustle of life.

“One of the things I cannot grasp,” Steiner writes, “is the time relation.” Steiner has just quoted descriptions of the brutal deaths of two Jews at the Treblinka extermination camp. “Precisely at the same hour in which Mehring and Langner were being done to death, the overwhelming plurality of human beings, two miles away on the Polish farms, five thousand miles away in New York, were sleeping or eating or going to a film or making love or worrying about the dentist. This is where my imagination baulks. The two orders of simultaneous experience are so different, so irreconciliable to any common norm of human values, their coexistence is so hideous a paradox, that I puzzle over time. Are there, as science fiction and Gnostic speculation imply, different species of time in the same world, ‘good time’ and enveloping folds of ‘inhuman time’, in which men fall into the hands of the living damnation?”

Stingo relates these observations to his own life, and Sophie’s; on a certain day in April 1943, he realises, when Sophie first entered the living hell of Auschwitz, he himself was busy gorging on bananas on a lovely spring morning in Raleigh, North Carolina, because he wanted to put on some weight before the physical examination for entrance into the Marine Corps. “On that day I had not heard of Auschwitz, nor of any concentration camp, nor of the mass destruction of the European Jews, nor even much about the Nazis.”

Note: Finished Jha’s book yesterday and thought it was outstanding: it’s a phantasmagoric story built around the terrible real-life events of those days, and he’s done it with both imagination and empathy. Am writing a full review but will only be able to post it after a few days, because it’s part of a long piece for The Hindu’s literary supplement and I’ll have to wait until it appears in print. Meanwhile, see this column Jha wrote in May 2002 – it was the seed of the book.

Some went into solitude with the book, but at the threshold of a serious breakdown they were able to open up to the world and shake off their affliction. There were also those who had crises and tantrums upon reading the book, accusing their friends and lovers of being oblivious to the world in the book, of not knowing or desiring the book, and thereby criticising them mercilessly for not being anything like the persons in the book’s universe.

Can’t recall the last time I was so frustrated by a book as I was by Orhan Pamuk’s The New Life. Maybe with Ishiguro’s The Unconsoled, which I blogged about here, but The Unconsoled was a book I grew to love – despite the initial bafflement and spots of intense irritation, I was drawn into its strange, surrealistic world. The New Life is another matter. It’s not easy to take to your heart, the way Pamuk’s Snow or My Name is Red are. It’s easier to admire than to like, and I was startled to learn that it was the fastest selling title in Turkish history when it was first published as Yeni Hayat in 1994. But even days after you’ve turned the last page, it’s difficult to stop thinking about it.

The New Life begins with the sentence “I read a book one day and my whole life was changed”. Through the often-abstruse narrative that follows, this line remains in a sense the closest summing up of what Pamuk’s book is about. The narrator is a young man, Osman (though we learn his name much later in the story), who first sees The Book in the hands of an attractive girl in college and buys it from a roadside stall on the way home. We don’t learn anything specific about the book at this stage, but we understand that Osman has become so affected by it that he comes to believe it has been created for him alone (which is, of course, exactly how many of us feel about things that matter a great deal to us). It seems to show him the path to a new world, the possibility of a new life; he gets obsessed with finding that life, even if it means discarding his present and turning his back on home and family.

The New Life begins with the sentence “I read a book one day and my whole life was changed”. Through the often-abstruse narrative that follows, this line remains in a sense the closest summing up of what Pamuk’s book is about. The narrator is a young man, Osman (though we learn his name much later in the story), who first sees The Book in the hands of an attractive girl in college and buys it from a roadside stall on the way home. We don’t learn anything specific about the book at this stage, but we understand that Osman has become so affected by it that he comes to believe it has been created for him alone (which is, of course, exactly how many of us feel about things that matter a great deal to us). It seems to show him the path to a new world, the possibility of a new life; he gets obsessed with finding that life, even if it means discarding his present and turning his back on home and family.

He meets the girl, Janan, as well as her friend Mehmet, who seems to know something about the “new life” described in the book. Soon after this, both of them disappear and the narrator himself leaves home, embarking on a series of dreamlike bus journeys across the country, many of which end in serious accidents (this isn’t commented on much, it’s treated as being an almost inevitable conclusion to a bus journey). He finds Janan again, and following another accident they set off for the town of Guzul to meet a man named Doctor Fine, who is part of “a struggle against the book, against foreign cultures that annihilate us, against the newfangled stuff that comes from the West, an all-out battle against printed matter”.

The New Life certainly touches on the eternal conflict between East and West, a theme that has run through all of Pamuk’s work (it’s poetic justice that the city in which he has lived most of his life straddles both Europe and Asia). But it can also be seen in more general terms, as an allegory about the different ways in which people respond to works of art and how they appropriate certain works for themselves, bringing their own hopes and desires to them – and in the process often setting themselves up for disillusionment. In this context there is great poignancy in the narrator’s ultimate discoveries about the book and how it came to be written, and his uncovering of the mundane truths behind the little signs that have come to mean so much to him.

It’s reasonably obvious (even from the premise) that The New Life is an example of metafiction – self-referential literature that is constantly drawing attention to itself rather than allowing the reader to sink into its world. This sort of thing occurs quite frequently in Pamuk’s books – in the multiple first-person narratives of My Name is Red, for instance (especially the chapters narrated by the “tree”, the “gold coin” and the “horse”), or that superb passage in the theatre-hall in Snow, where the curtain dividing artifice from real life is almost literally torn down.

Take this bit in The New Life, where the narrator learns about a young man’s meeting with an author named Rifki Ray:

Rifki Ray had tried closing the subject as soon as he realised the strange young man at his door was interested in the book. A touching interview could possibly have taken place between the youthful fan and the elderly writer, but for Rifki Ray’s wife – that’s Aunt Ratibe, I interjected – who had interfered, as I had done just now, and had pulled her husband inside.

Note the disconcerting effect of “that’s Aunt Ratibe, I interjected” in conjunction with “who had interfered, as I had done just now”. By likening his own action (“I interjected”) to something that occurs in the story he is being told, the narrator is drawing attention to his own status as just another character in a novel. In other words, he’s tearing down the fourth wall between himself and the reader.

Another example of Osman self-consciously examining his own actions occurs when he’s watching TV with an elderly lady and wants to broach a delicate topic. On the screen, a thriller has given way to a documentary, and he says:

In the wee hours of the morning, when the moaning, the murmurs in the night and the death throes were replaced by an educational film on the lives of red and black crabs in the Indian Ocean, I approached the topic sideways like the sensible crab on the screen.

The above sentence is also an example of Pamuk’s piquant sense of humour, something that seems improbable considering the huzun (the word for the very particular melancholy he describes as being endemic to his city, Istanbul) that influences and permeates his work. Many of his characters are very downbeat, and themes such as unrequited love, irreconcilable differences between people and general hopelessness about the future are common to most of his books. But as I mentioned in this post about Snow, he’s also very funny in a morbid, absurdist way.

Almost in spite of itself, The New Life has many laugh-out-loud bits. I loved the subplot about Doctor Fine hiring five spies to track his son’s movements: the men are given codenames that are watch trademarks – Omega, Zenith and so on – and after some time the narrator simply begins referring to them as “Dr Fine’s watches”. And the high comedy of this passage doesn’t in the least conflict with the fact that the “watches” in question are heartsick, disgruntled men, doing hard work for little reward (they reminded me of the depressed old detective who was hired to trail the poet Ka in Snow). Pamuk knows how to mix his huzun and his humour without undermining either quality.

[Did this piece for Biblio]

When Saradindu Bandyopadhyay created his amateur sleuth Byomkesh Bakshi in 1932, there wasn’t much of a homegrown tradition of detective fiction in Bengali (or, for that matter, Indian) writing; what little there was tended to be highly derivative of the West. In fact, by dabbling in a genre that was looked down on in highbrow literary circles, Bandyopadhyay risked not being taken very seriously as a writer. Today, however, the Byomkesh stories are what he is best known for, and they form one of Bengali literature's fondest legacies.

Non-Bengali readers like this reviewer spent long years hearing about these stories from friends, or watching some of them on the popular TV serial shown on Doordarshan a few years ago, without ever being able to read them firsthand. Occasionally a mediocre, indifferently edited translation would find its way to bookstores – hardly the best way to stoke reader enthusiasm. Then, a few years ago, Penguin India published Picture Imperfect, a collection of early Byomkesh Bakshi stories translated by Sreejata Guha, who did a fine job of capturing the spirit of the original stories. Now comes a new collection, again translated by Guha, which takes off from where the earlier book left off. Chronologically, the last story included in Picture Imperfect was "Chitrachor", originally published in 1952. The Menagerie and Other Byomkesh Bakshi Mysteries brings together four stories written between 1953 and  1967: "The Menagerie", "The Quills of the Porcupine", "The Jewel Case" and "The Will that Vanished" (originally published as "Chiriakhana", "Shojarur Kanta", "Monimondon" and Khuji Khuji Nari" respectively). The first two are novella-length while the others are short stories of between 20-25 pages.

1967: "The Menagerie", "The Quills of the Porcupine", "The Jewel Case" and "The Will that Vanished" (originally published as "Chiriakhana", "Shojarur Kanta", "Monimondon" and Khuji Khuji Nari" respectively). The first two are novella-length while the others are short stories of between 20-25 pages.

Set mainly in the Calcutta of the 1930s and 1940s, Bandyopadhyay's mysteries chronicle the varied triumphs of the detective (though Byomkesh prefers not to be addressed thus, calling himself a satyanweshi or "truth-seeker" instead), from the solving of peccadilloes like the theft of a necklace to the investigation of serious crimes such as a vicious murder. The tales are mostly narrated by Byomkesh's friend and flatmate Ajit babu (a writer by profession), though the later ones are marked by an increasing use of the third person.

The shorter stories here, which feel a little more dated, are mainly straightforward narratives hinging on a single important plot point – a careless utterance picked up and filed away by Byomkesh's sharp mind, an incongruity that no one else notices. If you're an experienced reader of detective fiction, some of the deductions will seem obvious, even naive. In one story, a letter written in invisible ink is the big plot twist (and no, this isn't a major spoiler). In another, Byomkesh lies sprawled on an armchair looking up at the beams on the roof and thinking for 15 minutes before making a fairly commonplace inference.

Of course, these pieces do serve their own function – they are cosy and undemanding, a throwback to the adventure stories that we used to read as children and occasionally revisit in our more nostalgic moments; one might comfortably breeze through them on a lazy Sunday afternoon just before a siesta, or even when there are 15-20 minutes free in the middle of the day. But it's the longer mysteries – represented in this collection by "The Menagerie" and "The Quills of the Porcupine" – that allow the author to expand the whodunit formula into a more searching examination of a society and the individuals who make it what it is.

Given the space to flesh out his plot and characters, Bandyopadhyay shows a fine eye for detail and social observation; his characters are nuanced and the stories are atmospheric, even sinister in a way that seems at odds with the comfortably bourgeoisie setting. They are also surprisingly candid about themes like extra-marital liaisons, which indicates that they were written in the first place for a mature readership – unlike another famous Bengali detective, Satyajit Ray's Feluda, whose adventures were primarily meant for children (on more than one occasion, Ray mentioned how difficult it was to write a mystery story with "no illicit love, no crime passionel and only a modicum of violence").

In "The Menagerie" (which, incidentally, was filmed by Ray under its original title Chiriakhana in 1967), Byomkesh and Ajit babu visit a strange private farm an hour's train journey from Calcutta, at the behest of its manager, Nishanathbabu. The place, called Golap Colony, is repeatedly referred to as a menagerie and even a "human zoo", and it's easy to see why – living in this self-contained little world are a number of odd characters, the dregs of society, who work for Nishanathbabu. Each of them is ill-placed, for one reason or the other, to earn a livelihood in a conventional fashion. Each of them has something to hide as well, which naturally adds up to quite a tangled weave when a murder is committed on the farm.

Thrilling though "The Menagerie" is in the classic detective story vein (there's even a little hand-drawn map of the farm and the various cottages on it), even more absorbing is "The Quills of the Porcupine", which was one of the last Byomkesh stories to be published. This novella is a classic example of how Bandyopadhyay became more ambitious in his later work, eschewing the traditional narrative format and turning his gaze to a larger canvas. In fact, Byomkesh makes his entry quite late into the story, and only after we as readers already know nearly all the facts of the case.

"The Quills of the Porcupine" centres on a seemingly random series of murders, each perpetuated with a porcupine quill, each victim belonging to a different class of society. As the plot unfolds, we realise that the murders are in some way connected to the lives of an unhappily married couple and a group of disparate characters who meet each evening for social chit-chat. Intercut with the murder mystery are observations on class and caste differences, the alienation inherent in big-city living, and the dual natures of people – though of course these musings don't preclude an exciting denouement featuring a bulletproof vest and Byomkesh using his "iron fist" to knock out a criminal.

In the most ambitious passage of the story, the omniscient narrator follows the nighttime lives of each of the principal characters, using their activities to comment on the dark underbelly of even the most conventional social orders. One gets a sense here of a society in transition, of the restlessness and disaffection of people who live in a big city, and how easily crime can breed in such a setting (at times, it's easy to forget that the period is the 1950s). Bandyopadhyay seems to be making a self-conscious attempt to transcend the trappings of his genre – though the narrative structure feels a little forced at times, it's an undeniably intriguing approach to what might otherwise have been a by-the-numbers mystery.

Of course, none of this means that the Byomkesh Bakshi mysteries can't be appreciated at the level of breezy, entertaining stories. One of the reasons I personally enjoy them is they evoke a very particular mood and milieu, an idyllic way of life that is as often the subject of nostalgia as of mirth in our fast-paced world. This involves the indolence that is stereotypically associated with Bengali intellectuals who prefer to flex their cerebral muscles rather than engage in much physical activity – the sort of lifestyle where one might spend the entire morning playing chess with a friend (as Byomkesh often does with Ajit babu) or leafing through the newspapers, then take an afternoon siesta and later wander across unannounced to a friend's house for tea and conversation.

Of course, none of this means that the Byomkesh Bakshi mysteries can't be appreciated at the level of breezy, entertaining stories. One of the reasons I personally enjoy them is they evoke a very particular mood and milieu, an idyllic way of life that is as often the subject of nostalgia as of mirth in our fast-paced world. This involves the indolence that is stereotypically associated with Bengali intellectuals who prefer to flex their cerebral muscles rather than engage in much physical activity – the sort of lifestyle where one might spend the entire morning playing chess with a friend (as Byomkesh often does with Ajit babu) or leafing through the newspapers, then take an afternoon siesta and later wander across unannounced to a friend's house for tea and conversation.

Conservation of energy is the key: it's no coincidence that words like "torpor" and "leisure" run through many of these tales. Here, for instance, is an account of a particularly stressful day for Byomkesh, smack-dab in the middle of an eventful case:

The morning crept in slowly. Putiram came in with the tea, but Byomkesh didn't touch it. Neither did he light a single cigarette. He lay in the armchair as if in a stupor, a hand sheltering his face.

At noon he got up in silence and had his bath and his lunch. Then he switched on the fan and stretched out on the bed. I knew he hadn't done so for a quick nap. He held himself responsible for Panugopal's death and needed solitude so he could come to terms with it. Moreover, he was desperate to unmask the shrouded assassin who had removed two people in quick succession from the face of the earth.

That evening, we sat and drank our tea together. Byomkesh's face continued to look as menacing as a newly sharpened razor blade.

And so it goes. Plenty of internal tension and deep thought, but nothing that would justify expending too much physical effort when it isn't strictly necessary.

At any rate, modern readers (especially those who haven't grown up with these stories) should find the Byomkesh Bakshi mysteries appealing on a number of counts. The Menagerie is a worthy introduction to Bandyopadhyay's work, though if possible it's advised to read Picture Imperfect first. Hopefully, all the stories will soon be translated and anthologised – the complete adventures of Ray's Feluda are now available in English translation in a two-volume set by Penguin India, and Bandyopadhyay's pensive satyanweshi deserves to be similarly honoured.

Lesson 3 from the Mahabharata: when your driver says nasty things to you, insult his lineage and question the character of the people from the region he belongs to. But do this in very ornate language, otherwise it will merely be in bad taste and not at all entertaining.

On Day 17 of the Kurukshetra War, as Karna sets out for his fated battle with Arjuna, his charioteer (by special request) is Shalya, the King of Madra. Unbeknownst to Karna, Shalya has conspired with the enemy to sap Karna’s morale and undermine his confidence at this crucial hour. This he now proceeds to do by saying things like “Arjuna and Krishna are like two mighty Suns and you are but a firefly in comparison, chirrup chirrup, muhahaha!” (I paraphrase slightly.) Whereupon Karna, never known for being able to hold his temper in check, embarks on this quite remarkable diatribe against the people of Shalya’s kingdom:

Hold thy tongue, O thou that art born in a sinful country. Hear from me, O Shalya, the sayings, already passed into proverbs, about the wicked Madrakas. There is no friendship in the Madraka who is mean in speech and is the lowest of mankind. The Madraka is always a person of wicked soul, always untruthful and crooked. It hath been heard by us that till the moment of death the Madrakas are wicked. Amongst the Madrakas, the sire, the son, the mother, the mother-in-law, the brother, the grand-son, and other kinsmen, companions, strangers arrived at their homes, slaves male and female, all mingle together. The Madraka is the dirt of humanity.

The women of the Madrakas mingle, at their own will, with men known and unknown. Of unrighteous conduct, and subsisting upon fried and powdered corn and fish in their homes, they laugh and cry having drunk spirits and eaten beef with garlic and boiled rice borrowed from elsewhere. They drink the liquor called Gauda, and eat fried barley with it. They sing incoherent songs and mingle lustfully with one another, indulging the while in the freest speeches. Maddened with drink, they call upon one another, using many endearing epithets. Addressing many drunken exclamations to their husbands and lords, these fallen women, without observing restrictions even on sacred days, give themselves up to dancing.

At this point I’m thinking that the Madrakas sound suspiciously like the protagonists of reality TV shows such as Big Boss. But Karna continues:

Knowing this, O learned one, hold thy tongue, or listen to something further that I will say. Those women that live and answer calls of nature like camels and asses, being as thou art the child of one of those sinful and shameless creatures, how canst thou wish to declare the duties of men? Intoxicated with drink and divested of robes, these women laugh and dance outside the walls of the houses in cities, without garlands and unguents, singing while drunk obscene songs of diverse kinds that are as musical as the bray of the ass or the bleat of the camel. In intercourse they are absolutely without any restraint, and in all other matters they act as they like.

Lesson 4: take your childhood heroes with a pinch of salt (or a dash of vinegar)

As a child, like every other warped little boy (and a few warped little girls) who came from a dysfunctional family and imagined he was the sole Outsider in a world where everyone else belonged, I hero-worshipped Karna. (I still do to an extent, though being an adult now I also like Ben Stiller.) Imagine then my astonishment when I came across the following lines spoken by this noble warrior, one of the great tragic heroes in all literature:

When a Madraka woman is solicited for the gift of a little quantity of vinegar, she scratches her hips and without being desirous of giving it, says these cruel words, 'Let no man ask any vinegar of me that is so dear to me. I would give him my son, I would give him my husband, but vinegar I would not give.' The young Madraka maidens, we hear, are generally very shameless and hairy and gluttonous and impure.

Suddenly, all the vignettes from the life of Karna, the long litany of misfortunes that gave such a sheen to the story of this unhappy hero, receded into the background, to be replaced by the surreal image of Karna, empty vessel in hand, asking for some vinegar and having the door rudely slammed in his face. It’s obvious from the above passage that Karna is greatly displeased at being spurned in his quest for vinegar. But why did he want so much vinegar in the first place? And why go to a Madraka woman to get it?

Suddenly, all the vignettes from the life of Karna, the long litany of misfortunes that gave such a sheen to the story of this unhappy hero, receded into the background, to be replaced by the surreal image of Karna, empty vessel in hand, asking for some vinegar and having the door rudely slammed in his face. It’s obvious from the above passage that Karna is greatly displeased at being spurned in his quest for vinegar. But why did he want so much vinegar in the first place? And why go to a Madraka woman to get it?

Questions, questions. Now I know what the sage meant when he said that every time you read the Mahabharata you will ponder the human condition anew.

Note: The passages quoted here are all taken from Kisari Mohan Ganguli’s exhaustive 12-volume English version of the epic (which you’ll find on the Sacred Texts site) and it’s possible that something was lost in translation from the original Sanskrit. Maybe “vinegar” was meant to be “wine”. (There are many other puzzling incongruities in the Ganguli text, such as one sentence that reads: “Jayadratha now rode against the mighty King Drupada, with his owl and his footsoldiers at his side.”)

Note: The passages quoted here are all taken from Kisari Mohan Ganguli’s exhaustive 12-volume English version of the epic (which you’ll find on the Sacred Texts site) and it’s possible that something was lost in translation from the original Sanskrit. Maybe “vinegar” was meant to be “wine”. (There are many other puzzling incongruities in the Ganguli text, such as one sentence that reads: “Jayadratha now rode against the mighty King Drupada, with his owl and his footsoldiers at his side.”)

Previous lessons from the Mahabharata: 1 and 2

Watching Shyam Benegal's Junoon (Obsession), about a weave of complex human relationships under the shadow of the 1857 War of Independence, I was reminded of Shashi Kapoor's dichotomous film career. At a time when the lines between "commercial" and "parallel" (or "art") cinema were very clearly defined, Kapoor was among the few actors/producers who bridged the divide, or tried to. In the late 1970s and early 1980s he was, on the one hand, doing a long line of now-forgotten commercial films (if you 're a Bolly-buff, check the 1975-1980 titles in his filmography and see how many you recognise), besides playing the thankless role of Amitabh's grinning jack-in-the-box sidekick in movies such as Suhaag, Trishul and Imaan Dharam. "You're like a taxi," big brother Raj told him once, meaning he would sign on with any producer who hailed him. But with the support and encouragement of his wife Jennifer Kendal, Kapoor used the money he made from commercial films to finance projects that were dearer to his heart (including critical successes such as Junoon, Kalyug, Vijeta and 36 Chowringee Lane), and to keep Prithvi Theatres running.

Watching Shyam Benegal's Junoon (Obsession), about a weave of complex human relationships under the shadow of the 1857 War of Independence, I was reminded of Shashi Kapoor's dichotomous film career. At a time when the lines between "commercial" and "parallel" (or "art") cinema were very clearly defined, Kapoor was among the few actors/producers who bridged the divide, or tried to. In the late 1970s and early 1980s he was, on the one hand, doing a long line of now-forgotten commercial films (if you 're a Bolly-buff, check the 1975-1980 titles in his filmography and see how many you recognise), besides playing the thankless role of Amitabh's grinning jack-in-the-box sidekick in movies such as Suhaag, Trishul and Imaan Dharam. "You're like a taxi," big brother Raj told him once, meaning he would sign on with any producer who hailed him. But with the support and encouragement of his wife Jennifer Kendal, Kapoor used the money he made from commercial films to finance projects that were dearer to his heart (including critical successes such as Junoon, Kalyug, Vijeta and 36 Chowringee Lane), and to keep Prithvi Theatres running.

Some of the “art” films of the 1970s and 1980s don’t hold up very well today – they seem overly concerned with saying Important Things and being the antithesis to the mainstream. However, Benegal’s movies generally managed to strike a balance. Junoon is an absorbing, very atmospheric film that nicely contrasts the grand and the small, the political and the personal. The theme of individuals finding grace even when the groups they belong to are busy killing each other requires the film to constantly move between a large canvas and an intimate one, and the director handles this shift very well.

As the story begins, the Mutiny has just begun, and Mariam Labadoor's (Kendal) husband is murdered by Indian sepoys in a church massacre. Living in an area that's in the eye of the storm, Mariam, her mother Mrs James (an Indian woman who married an Englishman decades earlier) and her young daughter Ruth seem destined for a similar fate but they are saved by an Indian acquaintance who risks his life to give them shelter in his house. A pathan, Javed Khan (Kapoor), soon discovers their whereabouts and takes them to his haveli; he is smitten by young Ruth and demands her hand in marriage. Mariam strikes a deal with him: "If the Indians succeed in capturing Delhi, Ruth is yours," she says.

This agreement is the film's strongest comment on the link between the personal and the political, but circumstances will later force Javed to wonder whether there should be any connection between the larger conflict and the relationships of the individuals caught up in it. These feelings are reflected in the film’s tone: it's almost as if war is a separate entity, a self-created monster that has nothing to do with human beings. But this is a whimsical, idealistic notion, as Javed will have realised by the end of the film.

Junoon is an acting powerhouse. Besides Kapoor and Kendall, there’s the luminous Nafisa Ali as the English rose, Ruth; she’s perfectly cast, though the character is underwritten. Shabana Azmi and Naseeruddin Shah have small but very effective parts respectively as Javed Khan’s insecure wife Firdaus and his bloodthirsty brother-in-law Sarfaraz. As the Englishwomen's kindly saviour Ramjimal there’s Kulbhushan Kharbanda, another actor who tried to bridge the parallel-commercial gap; his role here is worlds removed from the cartoonish villain Shakaal he played the following year in Ramesh Sippy's Shaan (yet another film that had Shashi Kapoor in an inconsequential role). And there are tiny parts for Pearl Padamsee (spewing venom at the debauched ways of the British, who “kiss each other on the mouths and use paper to clean themselves”), Sushma Seth and the young Deepti Naval.

Junoon is an acting powerhouse. Besides Kapoor and Kendall, there’s the luminous Nafisa Ali as the English rose, Ruth; she’s perfectly cast, though the character is underwritten. Shabana Azmi and Naseeruddin Shah have small but very effective parts respectively as Javed Khan’s insecure wife Firdaus and his bloodthirsty brother-in-law Sarfaraz. As the Englishwomen's kindly saviour Ramjimal there’s Kulbhushan Kharbanda, another actor who tried to bridge the parallel-commercial gap; his role here is worlds removed from the cartoonish villain Shakaal he played the following year in Ramesh Sippy's Shaan (yet another film that had Shashi Kapoor in an inconsequential role). And there are tiny parts for Pearl Padamsee (spewing venom at the debauched ways of the British, who “kiss each other on the mouths and use paper to clean themselves”), Sushma Seth and the young Deepti Naval.

One problem with the film is that the central relationship between Javed Khan and Ruth is not very convincingly handled. In Shashi Kapoor's performance there is a sense of obsessive lust slowly turning into something more tender and protective, but we never get a real insight into Ruth's feelings, of how and why her initial fear of Javed turns into love. The script gives us shorthand instead of believable emotion – at one point when Javed has ridden off into battle, Ruth asks her mother, "Do you think he will return, mama?" (incidentally this is the only full sentence I can remember Nafisa Ali speaking in the film) and we must be content with that as an indication that she's genuinely concerned about him.

As a result, the last scene lacks dramatic weight. The final title card informs us pedantically that Javed was killed in battle and that "Ruth died 55 years later in London, still unwed", but nothing earlier in the film ever pointed to such intensity of feeling on her part. The title feels like it was written to cater to male fantasies about young girls who "save themselves" for their True Loves, or eternal romantics who dream about love conquering race, religion and even time. (Lagaan had an equally unconvincing coda about the Rachel Shelley character vis-à-vis Aamir Khan’s Bhuvan.)

But it would be a pity to judge Junoon by its abrupt and unsatisfying ending. There’s much to admire in this film, many scenes that linger in the mind: the perpetually worried look on Mariam’s face (a single glance from Jennifer Kendal could convey as much as another actor armed with pages of dialogue); a mad prophet rolling his eyes wildly and predicting that the British time in India is over; the English refugees and the Indian women washing their clothes in separate corners of a courtyard; Ramjimal saying farewell to Mariam and telling her “bitiya ko mera salaam kehna” (the “bitiya” being a young girl who doesn’t even share a language with him); Javed Khan trembling with unrequited passion as he talks about wanting to possess Ruth; Sarfaraz’s assault on the caged pigeons, whom he blames in his madness for the sepoys having lost Delhi; Ruth’s recurring nightmares (including one about rape, and another of Sarfaraz snarling and animal-like, bound to a British cannon and being blown to pieces); the look on Firdaus’s face as she realises how completely lost Javed is to her.

And then there’s one of the quietest moments in the film, a charming little scene by a swing in a garden, where four women (two Indian, two British) find a few moments of peace and companionship by, in turn, singing songs from each of their traditions. It doesn’t matter that neither song can be fully understood by all the women. What matters is that for this brief repose the battle cries have been pushed into the background. In the languor of this moment it’s even possible, very briefly, to believe in Javed Khan’s grand conceit that individual feelings can be separated from group dynamics in times of war.

Via Falstaff, I just read this fine piece by Slate’s Dan Kois, comparing the careers of U2 and R.E.M. in the 1980s and 1990s. I love both bands, or used to back in the days when I actually listened to music and life was something more than a bleak wasteland littered with books and films: being more of an “albums person” than a “singles person”, I spent weeks on end being obsessed by, in turn, U2’s War, The Unforgettable Fire, The Joshua Tree, Achtung Baby and yes, even the reviled Zooropa; and by R.E.M.’s Murmur, Out of Time, Automatic for the People, New Adventures in Hi-Fi, Up and Reveal.

Am slightly more of an R.E.M. man overall, though I suspect U2’s superstar status/high profile has led some listeners to undermine the quality of their music, which has been extraordinarily good for close to 30 years now (they started off as a school band in the late 1970s). Also, much as I love Michael Stipe – his effete preciosity, his soporific voice, the obscure lyrics and some of the self-consciously campy things he does in music videos (watch “Lotus” or “The One I Love”) – Bono is still my pick for the world’s greatest singer.

At any rate, they are both great bands, their work taken together covers a vast spectrum and has enriched popular music immeasurably – so why not appreciate both instead of getting into the “R.E.M. vs U2” debate? You know, it's all about life’s rich pageant and so forth (that’s the title of an early R.E.M. album incidentally).

P.S. One point where I disagree with Kois is his casual brushing aside of R.E.M.’s achievements in the 1990s. That’s the period when they did some of their finest, most challenging work. On that note, do read this excellent piece by Jaideep Varma, from a 1999 issue of Gentleman magazine: “The World’s Finest Band: How R.E.M. went beyond the American Dream”.

So there I am watching Oliver Stone’s World Trade Center, about the rescue efforts in the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, and specifically the ordeal of two firefighters trapped under a huge heap of rubble. Up on the screen, the wives and families of the two men are (quite understandably) alternating between hysteria and calculated stoicism, and there’s generally heaps of emotion on display - both suppressed and vented. And then a friend leans across and says, “Isn’t all this a bit Hindi film-ish?”

I get peeved when people use the term “Hindi film-ish” loosely (and with a hint of condescension) to describe anything they feel is melodramatic or overwrought (hence “unrealistic”). Two reasons for this: one, Hindi movies didn’t invent the tradition of melodrama, it’s existed in different forms across cultures, and for long before cinema came into being. Attributing anything that’s perceived as overly dramatic to “the Bollywood influence” is every bit as uninformed as watching a Hollywood musical for the first time and saying “yeh toh hamaare Hindi films ki copy hai”.

The other reason has to do with something I’ve discussed on this blog before – the fact that cinematic “realism” is a chimerical thing at the best of times. A very basic example: a scene where a man beats his chest and wails loudly in the face of tragedy might seem melodramatic, even unrealistic, to a viewer who doesn’t believe in showy displays of emotion in public. But different people have different realities: what’s being depicted in that scene might be completely consistent with the way that character would react in that situation. All that matters is the consistency with which the film depicts a specific, self-contained world.

Also, as Vikram Chandra nicely articulated in this interview, “what is overly emotional/melodramatic anyway? I look around me at Indian families and by God, we're so melodramatic in real life!” (Can’t help agreeing with him there; I’m an unexpressive, emotionally constipated piece of deadwood myself, but you should see the stuff that goes on in my family – such as daily morning fights with housemaids that turn into orgies of recrimination, tears and emotional blackmail.)

World Trade Center isn’t about Indian families, but that's hardly the point here. Think about it: something as momentous as 9/11 happens, thousands of people first recoil in horror, then panic, break down, spend hours lashing out at each other and comforting each other, and end the day either with tears of relief or by grieving horribly. Given all this, is it so hard to believe that there were instances of REAL people behaving in ways that would seem embarrassingly “melodramatic” and “Hindi filmi” when watched onscreen? The problem is to a large extent with our own perceptions; too many of us have been conditioned to be uncomfortable about (and suspicious of) any cinematic portrayal of extreme emotion.

The film

I had mixed feelings about World Trade Center – not because of the dramatic scenes but because (and I know this is actually a pointer to the film’s effectiveness) it made me feel very tired and claustrophobic. This will happen when the bulk of a film involves two men (characters you’ve come to know and sympathise with) buried several metres below the ground, unable to even move, simply talking to each other in order to stay awake and sane. That’s the real-life story of policemen John McLoughlin (Nicolas Cage) and Will Jimeno (Michael Pena), two of only 20 people who were pulled out alive from the wreckage of 9/11. McLoughlin and Jimeno entered the buildings as part of a rescue squad, hoping to save at least some of the people trapped on the upper levels, but they never got a chance to do anything seriously heroic, in fact never even made it beyond the ground floor; just a few moments into the operation, they were the ones who needed rescuing.

I had mixed feelings about World Trade Center – not because of the dramatic scenes but because (and I know this is actually a pointer to the film’s effectiveness) it made me feel very tired and claustrophobic. This will happen when the bulk of a film involves two men (characters you’ve come to know and sympathise with) buried several metres below the ground, unable to even move, simply talking to each other in order to stay awake and sane. That’s the real-life story of policemen John McLoughlin (Nicolas Cage) and Will Jimeno (Michael Pena), two of only 20 people who were pulled out alive from the wreckage of 9/11. McLoughlin and Jimeno entered the buildings as part of a rescue squad, hoping to save at least some of the people trapped on the upper levels, but they never got a chance to do anything seriously heroic, in fact never even made it beyond the ground floor; just a few moments into the operation, they were the ones who needed rescuing.

The summer’s other 9/11 film was United 93 (which I reviewed here), and though that was docudrama-like in its treatment, there’s something inherently gripping about the story of an airplane held hostage by terrorists. By comparison, the basic scenario in World Trade Center – two men conclusively trapped underground, with nothing to do but wait for help – is a static one. Oliver Stone tries to compensate for this by incorporating a number of flashbacks, mostly in the form of the hallucinations experienced by the buried men as they drift between consciousness and semi-consciousness. Unfortunately, these bits don’t hold up too well – they jar with the rest of the film. Showing the tribulations of the wives and families works well enough as visual relief.

But World Trade Center is an indisputably well made film otherwise, at its very best in the early scenes where the firefighters, led by McLoughlin, reach the general vicinity of the skyscrapers and slowly start to edge their way towards the rumbling buildings. This is stuff that the finest horror-movie directors would have been proud of – you get a visceral, firsthand impression of what it must have been like for those men to approach the Twin Towers (at that point, no one imagined that the two buildings would come crashing down, but it must have been terrifying even without that knowledge).

But World Trade Center is an indisputably well made film otherwise, at its very best in the early scenes where the firefighters, led by McLoughlin, reach the general vicinity of the skyscrapers and slowly start to edge their way towards the rumbling buildings. This is stuff that the finest horror-movie directors would have been proud of – you get a visceral, firsthand impression of what it must have been like for those men to approach the Twin Towers (at that point, no one imagined that the two buildings would come crashing down, but it must have been terrifying even without that knowledge).

We don’t actually see the towers too often in this scene (the abiding image is that of thousands of sheets of paper pouring out of the windows, like a nightmare version of those glass paperweights you turn upside down to simulate a snowfall), but we feel their awesome presence at all times – this is one of the few times that I’ve found the Dolby experience to be really effective in a movie hall. It’s like two angry active volcanoes have been transplanted to this urban setting and the firefighters are walking right into the heart of the inferno. This is an incredibly effective scene, and what follows is only marginally less gripping. Compared to some of Oliver Stone's recent work (Alexander, U-Turn, even Any Given Sunday) this is a surprisingly straightforward film – it looks like he's rediscovered the merits of good old-fashioned storytelling.

I so wish I could begin this post by saying I loved Jaan-e-Mann without reservation and recommend it to everyone unconditionally. For a solid one-and-a-half hours, Shirish Kunder’s directorial debut is a delightful, thoroughly absorbing film. I sank wholeheartedly into its marvelous stage-musical world, the constant self-referencing and clever sight-gags, the gorgeosity of the song “Humko Maloom Hai” and its picturisation, the tributes to Singin' in the Rain, What Price Hollywood? and even the dancing space stations of 2001: A Space Odyssey (yes!), and the performances of Akshay Kumar, Salman Khan and Preity Zinta. (All this was so well done that I was happy to overlook the one sour note in the film’s first half: the unfortunate bit of lowbrow slapstick involving Anupam Kher playing Salman’s midget uncle – with much tasteless punning on the word “bauna”, meaning dwarf.)

I so wish I could begin this post by saying I loved Jaan-e-Mann without reservation and recommend it to everyone unconditionally. For a solid one-and-a-half hours, Shirish Kunder’s directorial debut is a delightful, thoroughly absorbing film. I sank wholeheartedly into its marvelous stage-musical world, the constant self-referencing and clever sight-gags, the gorgeosity of the song “Humko Maloom Hai” and its picturisation, the tributes to Singin' in the Rain, What Price Hollywood? and even the dancing space stations of 2001: A Space Odyssey (yes!), and the performances of Akshay Kumar, Salman Khan and Preity Zinta. (All this was so well done that I was happy to overlook the one sour note in the film’s first half: the unfortunate bit of lowbrow slapstick involving Anupam Kher playing Salman’s midget uncle – with much tasteless punning on the word “bauna”, meaning dwarf.)

Unfortunately, after the intermission, the film lost its distinct style (and, crucially, much of its sense of humour), turning into a prosaic story with leaden dialogues and going on for at least half an hour too long. (I know I’ve been saying that a lot recently, but when you’re watching a movie at night in a hall that’s a one-hour drive from your home and you’re mentally geared for it to be over by 10 PM and it goes on till 10.45 and it’s been a long day … trivial though it seems, on such things do our lasting impressions of movies often hinge.)

And yet, despite the disappointment that comes from an immensely promising film losing the plot, the good bits were so brilliant I can’t get them out of my head. This is one of those times where I’m grateful I’m not reviewing professionally (especially for a newspaper that demands dumbed-down reviews and offers you just 400 words to be dumb in), because then I’d have to get into the business of evaluation – talking down to the reader, summing the film up in a few lines, explaining loftily why it’s Good or Bad. Writing in this medium, on the other hand, allows me to forget the bad and remember the good, to unapologetically talk about the many things I loved about the film.

In short, Jaan-e-Mann is about Suhaan Kapoor (Salman Khan), a budding actor who becomes distanced from his wife Piya (Preity Zinta) when his career seems about to take off; they get divorced, things subsequently turn bad for him and he can’t afford to pay the alimony. Just as he and his midget-uncle are scratching their heads about what to do next, in walks Agastya Rao (Akshay Kumar), a NASA astronaut and all-round geek who was besotted with Piya in college. Suhaan now plots to take Agastya to NY, re-acquaint him with Piya and eventually get them married off so she isn’t a financial burden on him any more.

In short, Jaan-e-Mann is about Suhaan Kapoor (Salman Khan), a budding actor who becomes distanced from his wife Piya (Preity Zinta) when his career seems about to take off; they get divorced, things subsequently turn bad for him and he can’t afford to pay the alimony. Just as he and his midget-uncle are scratching their heads about what to do next, in walks Agastya Rao (Akshay Kumar), a NASA astronaut and all-round geek who was besotted with Piya in college. Suhaan now plots to take Agastya to NY, re-acquaint him with Piya and eventually get them married off so she isn’t a financial burden on him any more.

There’s heaps to relish here. There’s the enthralling black-and-white montage of scenes from Filmfare Awards ceremonies from the early 1970s (featuring Raj Kapoor, Dharmendra, Rajesh Khanna, Mumtaz, Sanjeev Kumar and Amitabh among others) in a Forrest Gump-meets-JFK-style fantasy sequence where Salman is presented a special trophy by Meena Kumari and goes on to thanks his buddies “Meena, Kaka, Amit, Dharam”. There’s the completely superfluous but still delightful shot of seven helicopters spelling out “New York” when the action shifts to that city. And Akshay Kumar’s infectious nerdishness, his Beavis-and-Butthead laugh – huh uh huh uh huh – which seems puerile at first but see if you don’t find yourself imitating it hours after you’ve seen the film.

There’s Salman dressed up as a statuesque woman in a nightclub (he participates in the film’s only fight scene in this outfit) and the mild dig at superhero films like Krrish when he dons a Zorro outfit with a black mask covering just the upper part of his face and muses “Now no one will recognise me”. And there’s a lovely scene where the two men, having trained a telescope (!!) on Piya’s living room and projected her “Live” image on their room wall, look at her crying as she watches a romantic film and end up in tears themselves – eventually falling asleep in each other’s arms. (Just by and by, what a fine screen couple Salman and Akshay make – remember Mujhse Shaadi Karogi? The girl is almost redundant.)

There’s the deliberate, self-aware theatricality of the song sequences – so Broadway-like, so different from the standard Hindi film idiom. (Musicians and back-up dancers materialise when a song situation arises; when it’s over they exit the room muttering “Arre, jaldi karo”, like the band-baaja wallahs at a shaadi, once they’ve been paid for their efforts.) When characters reminisce about their past, they walk into their own flashbacks, asking peripheral figures to “clear the frame, please”. The need for a sutradhar character and for persistent commentary is so strong that when our heroes make it to New York, leaving the midget uncle behind (thankfully!), what do we have but Anupam Kher showing up as an unrelated character and essentially proceeding to perform the same function that he did in the early scenes as the uncle – listening to the heroes’ problems, conniving with them and such (soon Salman even starts calling this stranger “maamu”, and it doesn’t feel odd).

There’s the deliberate, self-aware theatricality of the song sequences – so Broadway-like, so different from the standard Hindi film idiom. (Musicians and back-up dancers materialise when a song situation arises; when it’s over they exit the room muttering “Arre, jaldi karo”, like the band-baaja wallahs at a shaadi, once they’ve been paid for their efforts.) When characters reminisce about their past, they walk into their own flashbacks, asking peripheral figures to “clear the frame, please”. The need for a sutradhar character and for persistent commentary is so strong that when our heroes make it to New York, leaving the midget uncle behind (thankfully!), what do we have but Anupam Kher showing up as an unrelated character and essentially proceeding to perform the same function that he did in the early scenes as the uncle – listening to the heroes’ problems, conniving with them and such (soon Salman even starts calling this stranger “maamu”, and it doesn’t feel odd).

Even the things one would usually consider irritants are put to good use here. Akshay Kumar’s unremarkable voice (often cited as a reason why he never became a really big star) is completely suited to Agastya’s bland personality. And Salman Khan’s self-conscious, Yank-accented English works superbly in a couple of scenes, including one with an air-hostess and another where he shrugs off a TV scriptwriter.

In praise of Salman

Jaan-e-Mann is nothing if not self-referential, and I thought it was interesting how some scenes are almost like a commentary on Salman Khan’s career. An admission here, which research suggests will cut my blog traffic by 15 per cent: I’m a closet Salman fan. (Okay, just a Salman fan now.) I’ve enjoyed his willingness to risk looking ridiculous onscreen right from the time he ran around a college campus in a bikini for a ragging scene in a very early film, Baaghi – how many other good-looking hunks do you know who are open to becoming objects of derision? In comic roles, he’s often very good. As a dramatic actor he’s sometimes laughably bad (which still makes him fun to watch), but there’s also a directness, a transparency about his performances that can be effective when he’s in good hands; some of his emotional scenes in Jaan-e-Mann aren’t bad at all.

It’s been difficult in recent years to separate Salman’s loveably goofy, self-effacing screen image from the unpleasantness of his real-life doings (running over sleeping people on pavements, slaying endangered deer, being nasty to Aishwarya Rai – oh wait, does that count as a character flaw?) but I’ve managed somehow to retain a morbid affection for him through it all, and I like the way this film played with his image. Take the montage scene where, after a series of unsuccessful auditions (inspired by Gene Kelly’s “Dignity. Always dignity” sequence in Singin' in the Rain), he removes his shirt, flexes his muscles and is promptly signed on by a producer. Or his character’s refrain that he only accepts “main lead” roles (which quickly becomes ironical in a film where Akshay Kumar is playing the conventional romantic lead for the most part). And later, when Piya tells Agastya, “I feel so bad for Suhaan, no one ever has anything good to say about him but he’s good at heart,” it almost feels like an appeal for Salman Khan.

Okay, since I realise how enthusiastic this post has been, let me get back to being defensive: Jaan-e-Mann does fall short in the final reckoning, and if anyone goes to watch it based on this post and then comes back and complains to me, I’m simply going to go “I told ya so”. (One thing I found especially problematic is that a couple of the songs are downright mediocre – not a good sign for a musical of this type.) But if this film is unsatisfying on the whole, it also contains at least an hour’s worth of entertainment that’s richer and more dazzling (if you’re willing to open yourself to all the strangeness) than almost anything else that has come out of Bollywood so far this year. So there!

P.S. Much enjoyment comes when a reviewer you greatly admire is in 80 per cent agreement with you about a film. Do read Baradwaj Rangan’s excellent review (the unedited version, please).

Had a nice little talk a few days ago with Moonis Ijlal, a young artist who's done some fine book covers for Rupa and Picador. Indian publishers haven’t always given cover designs the attention they deserve (though this appears to be changing now) and when Moonis did his first cover, for Inez Baranay's Neem Dreams, no one was quite prepared for how seriously he would take the assignment. He read the book in its entirety (itself something not many designers do; most are content with a brief along by the author’s inputs, if any), then set about creating a collage by scanning neem leaves, nails and even cigarette butts.

Had a nice little talk a few days ago with Moonis Ijlal, a young artist who's done some fine book covers for Rupa and Picador. Indian publishers haven’t always given cover designs the attention they deserve (though this appears to be changing now) and when Moonis did his first cover, for Inez Baranay's Neem Dreams, no one was quite prepared for how seriously he would take the assignment. He read the book in its entirety (itself something not many designers do; most are content with a brief along by the author’s inputs, if any), then set about creating a collage by scanning neem leaves, nails and even cigarette butts.

"One of the key elements of my design," he tells me, "was a milestone that simply had the number zero on it." When the author and the publisher asked him about it, he explained that it was his interpretation of the place where all journeys begin and end – a theme that’s alluded to in the book. "They were pleasantly surprised that I had actually put some thought into it!" he says.

"One of the key elements of my design," he tells me, "was a milestone that simply had the number zero on it." When the author and the publisher asked him about it, he explained that it was his interpretation of the place where all journeys begin and end – a theme that’s alluded to in the book. "They were pleasantly surprised that I had actually put some thought into it!" he says.

One of Moonis's preferred styles is the use of mixed media – the strategic placement of many small images at different points on the book cover. This is on view in his design for Rahul Bhattacharya's Pundits from Pakistan (the images include a bowler down on his knees and appealing, an overloaded truck and sundry photographs from Pakistan) as well as for Pankaj Mishra's India in Mind and the 50 anniversary edition of A L Basham's The Wonder that was India (it was serendipitous that he was asked to work on this edition, for the book is one of his all-time favourites).

He also did the design for the Chetan Bhagat blockbuster Five Point Someone, with three cogs representing the principal characters (the three IIT loafers, including the narrator), a flower representing the young heroine and a single shoe her brother, a suicide. "Chetan never cared much for that stray shoe, he thought it was too oblique and pretentious" Moonis smiles, "but eventually I got my way."

He also did the design for the Chetan Bhagat blockbuster Five Point Someone, with three cogs representing the principal characters (the three IIT loafers, including the narrator), a flower representing the young heroine and a single shoe her brother, a suicide. "Chetan never cared much for that stray shoe, he thought it was too oblique and pretentious" Moonis smiles, "but eventually I got my way."

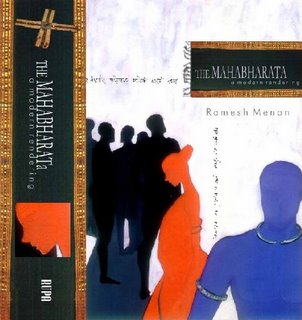

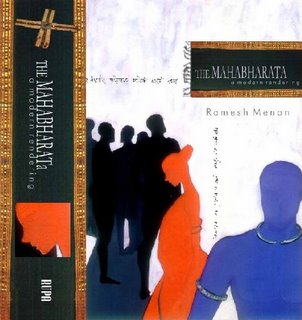

He’s used to getting his way – when he works on a cover, he takes over the whole space, even deciding where and how the title should appear. His covers for Ramesh Menon's two-volume Mahabharata demonstrate this holistic treatment. Both covers feature small excerpts from the book's text, written in his own hand (this is another motif of his designs). "Since I read the whole book before preparing the design, I use little passages or sentences that I find particularly striking." On the cover of the first volume are featureless figures representing the Pandavas at the game of dice, the humiliated Draupadi, and Krishna standing in the foreground – identifiable mainly by his blue skin. The characters have short, cropped hair: "I wanted the contemporary look, because this is a great contemporary story," he explains.

The second volume, which deals mainly with the terrible Kurukshetra war, has an aptly stygian look – a flock of ravens seen against a darkening sky – with just one bright spot, a white lotus that, he says, “represents the Bhagwad Gita, the sole light of hope in this dark tale". Another striking aspect of the design is the way the word "Mahabharata" is written on the back covers – in both the Hindi and the Urdu scripts, one word entwined with (and seeming to reach out to) the other. "The publishers weren't too sure about including the Urdu version," Moonis says, "but I pointed out that this is a universal story that belongs to everyone, not just to Hindus. It’s a great human tale that can unite people of completely different backgrounds."

The second volume, which deals mainly with the terrible Kurukshetra war, has an aptly stygian look – a flock of ravens seen against a darkening sky – with just one bright spot, a white lotus that, he says, “represents the Bhagwad Gita, the sole light of hope in this dark tale". Another striking aspect of the design is the way the word "Mahabharata" is written on the back covers – in both the Hindi and the Urdu scripts, one word entwined with (and seeming to reach out to) the other. "The publishers weren't too sure about including the Urdu version," Moonis says, "but I pointed out that this is a universal story that belongs to everyone, not just to Hindus. It’s a great human tale that can unite people of completely different backgrounds."

Notwithstanding the care he puts into his designs, he’s quick to say that the most important thing is that the cover should be appealing. "I don't mind much if the casual reader doesn't notice all the little elements I've included in the design, or think too hard about their significance" he says, "as long as the overall effect is pleasing."

Notwithstanding the care he puts into his designs, he’s quick to say that the most important thing is that the cover should be appealing. "I don't mind much if the casual reader doesn't notice all the little elements I've included in the design, or think too hard about their significance" he says, "as long as the overall effect is pleasing."

P.S. Incidentally, Bena Sareen, the group art director for Penguin Books India (one of the few publishers to have a full-fledged in-house design team), says the design lines between literary and genre fiction have become blurred. "Even highbrow literary works are being marketed as accessible," she says. It's no longer necessary for a work by, say Saul Bellow, to look more austere than a book by a genre writer. On that note, two stories from the Guardian about Penguin’s “designer books”, commissioned to celebrate the 60 anniversary of Penguin Classics. Five leading designers were asked to choose a favourite book from the backlist and to design it as they wanted. See what they did and what they have to say about it: Cover Versions and Cover Stories.

P.S. Incidentally, Bena Sareen, the group art director for Penguin Books India (one of the few publishers to have a full-fledged in-house design team), says the design lines between literary and genre fiction have become blurred. "Even highbrow literary works are being marketed as accessible," she says. It's no longer necessary for a work by, say Saul Bellow, to look more austere than a book by a genre writer. On that note, two stories from the Guardian about Penguin’s “designer books”, commissioned to celebrate the 60 anniversary of Penguin Classics. Five leading designers were asked to choose a favourite book from the backlist and to design it as they wanted. See what they did and what they have to say about it: Cover Versions and Cover Stories.

Nilanjana has a lovely full-page piece on William Dalrymple and The Last Mughal in today’s edition of the Business Standard Weekend (online link here, though it’s much more satisfying to read in the print version). They walk around Mehrauli’s Zafar Mahal (which used to be Bahadur Shah Zafar’s summer palace), discuss Dalrymple’s book, the forgotten treasures of Delhi and the lack of accessible writing about historical figures in India…and then they run into a direct descendant of the Emperor.

The gentleman makes a small, deprecating gesture and says gently, “I wanted to tell you to write about Zafar’s court, many mistakes have been made in the accounts, about Ilahi Baksh and others.” We stand in a small knot, flanked by the dargah, Zafar Mahal and nouveau kitsch buildings, discussing the members of Zafar’s court with as much passion as contemporary Dilliwallas bring to a discussion of, say, Sonia Gandhi’s inner circle.

“So modest,” says Dalrymple as we make our polite, courtly farewells. “He identified himself as ‘Pakeezah’s cousin’ — another man would have said outright, I am the descendant of Bahadur Shah Zafar.” He should be used to the unusual encounter, the strange coincidence, but there is something rather wonderful about meeting a descendant of the emperor as we emerge from Zafar Mahal, on the day of one of the best-loved festivals of Mughal and modern times.

Full piece here.

From a special supplement on Aishwarya Rai, titled “Beyond the Beauty”, by The Times of India:

What is most commendable is that despite critical criticism from her critics (sic) for her much over and under acting (sic), she overcomes all to still find herself on [American] national television…

[They’re right, you know. I’m probably one of those “critically critical critics” (ref. this post) and I do feel quite “overcome” now.]

From the same supplement:

What also makes Aishwarya stand out among her peers in Bollywood is that in her interview with Oprah Winfrey, she made no bones that characterises a new entrant in Hollywood, especially from this part of the world.

[Maybe it’s all the mythology I’ve been reading, but “made no bones” makes me think of Indra slaying Vritra with a weapon fashioned from the bones of the rishi Dadhichi. What does it say about me, I wonder, that I read the ToI in the morning and the sacred Puranas at night?]

Still on Aishwarya, this time from the column Mandira Bedi has been writing for Hindustan Times during the cricket series. Apparently, Ms Rai dropped in at the studio to chat with Mandira and Charu Sharma a few days ago. Mandira writes:

After much urging, we prompted speechless Charu to ask her how it felt to be among the most beautiful women in the world. The credit was attributed to her fans, as she commented on how people’s love is truly very humbling.

[“Humbling”? Shouldn’t that be “beautifying”? But really, if she’s as witty as the ToI supplement made her out to be, she should have answered Charu thus: “Oh, it feels alright. But you tell me, how does it feel to be the most half-witted sports anchor in the world?”]

“Indian culture does not allow women heroism,” says an insider.

[From Delhi Times front page. Don’t ask.]

And this from a ToI story about Ram Gopal Varma having cast Nisha Kothari as Basanti in his Sholay remake (though Basanti will now be called Ghungroo):

Giving a peek into the Ghungroo character, he adds, “She likes you to believe she’s a man. But inside she is all woman.”

[They could have removed the word “character” from the above sentence, methinks, without much affecting its tone.]

In the original Sholay, the characters of Hema Malini and Jaya Bachchan never came face to face. But in “Ram Gopal Varma ke Sholay”, Varma will get his two heroines to have an interface (sic).

[I mean, really, how difficult can it be to just say “the two heroines will be together onscreen” or “they will share a couple of scenes”? As Amit points out, this sort of purplocity requires more effort than good writing does.]

…I liked Don on the whole, though it dragged towards the end and got all confused, what with all the intersecting sub-plots (and the two major twists). And yes, I thought Shah Rukh was very good in the first half (gasp away, people. K-k-kill me for saying it) where he plays the character his own way, not allowing the Amitabh legacy to cramp his style. The moment he struck up that pose in the room full of ballet dancers, in the very first scene of the film, I knew he wouldn’t screw up.