In recent years I’ve rarely travelled more than three or four km beyond Saket unless it’s for an important appointment; I don’t attend most of the book-related events I get invites for, especially the ones held near Connaught Place (spending an hour each way on the road and driving in circles to find parking space is not my idea of evening fun). Besides, our colony has become an autonomous little village since the malls opened. With a variety of good restaurants and coffee joints, bookstores, music stores, plenty of walking and sitting space, and pretty much everything else one needs, there hasn’t been much incentive to go to, say, Khan Market, which was once a regular haunt.

Now the Metro is changing this to an extent. When I wrote this post in 2008, it seemed like the construction would go on forever and we’d never get to see actual trains (all we saw then were hordes of solemn-faced, helmeted men wandering about our park with giant measuring instruments, occasionally visiting houses to take photos of every crack on every wall so we couldn’t subsequently blame the damage on the vibrations). But it’s all in working order now, and a huge convenience – these days I sometimes find an excuse to get out for a while even if I don’t strictly have to.

Now the Metro is changing this to an extent. When I wrote this post in 2008, it seemed like the construction would go on forever and we’d never get to see actual trains (all we saw then were hordes of solemn-faced, helmeted men wandering about our park with giant measuring instruments, occasionally visiting houses to take photos of every crack on every wall so we couldn’t subsequently blame the damage on the vibrations). But it’s all in working order now, and a huge convenience – these days I sometimes find an excuse to get out for a while even if I don’t strictly have to.The initial sense of well-being comes from the fortunate location of the two Yellow Line stations in the Saket area. The so-called Malviya Nagar station is a minute’s walk from my mother’s flat where I lived for over 20 years (and where I still spend most of my working day), while the Saket station is a minute’s walk from our other flat. This makes the decision to travel by train a straightforward one. If I have to go to Connaught Place or even somewhere closer like Green Park or Dilli Haat (right next to the INA station), it’s a no-brainer. In the winter months, it's a comfortable 2-km walk from the Jor Bagh station to Khan Market or the India Habitat Centre (where the Penguin Spring Fever fest is starting today) or the Alliance Francaise (where I was in conversation with Namita Gokhale yesterday).

The stations are spacious and (at this point anyway) clean, and the trains run smoothly most of the time; so far I’ve found an empty seat on only two occasions, but standing isn’t a problem for a trip that takes 20-25 minutes at most. If I had to nitpick, I’d say that travelling on the Saket-Rajiv Chowk route can be monotonous – the entire line is underground, nothing to see outside the windows, and reading isn’t really an option if you’re standing and the train is crowded. (The journey in the opposite direction to Gurgaon – with the line elevating as it approaches Qutab Minar – is pleasanter.)

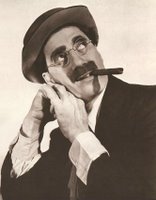

But on the whole - massively empowering. I can think of only one possible improvement: given that a section of the Malviya Nagar station is located directly under our house, it would be most useful if we could get digging rights and install a sliding pole that would take me directly from my room to the platform a few metres beneath (like Groucho shinning down the fire pole into the ballroom in Duck Soup). But that’s the lazy, mollycoddled, freelancing homebody talking again, and you’re free to ignore anything he says.

[As a tribute to crowded trains, here’s the great opening scene of Sam Fuller’s Pickup on South Street, a film I wrote about here]

[As a tribute to crowded trains, here’s the great opening scene of Sam Fuller’s Pickup on South Street, a film I wrote about here]